“With the emergence of the Web, the preconditions were available to us to really think boldly about reshaping the arts and humanities fields in a way that would allow for the building of bigger pictures,” said Jeffrey Schnapp, a professor of Romance languages and literatures. “The Internet allows us to bring scholarship out of the silos in which it lives into an interdisciplinary conversation.”

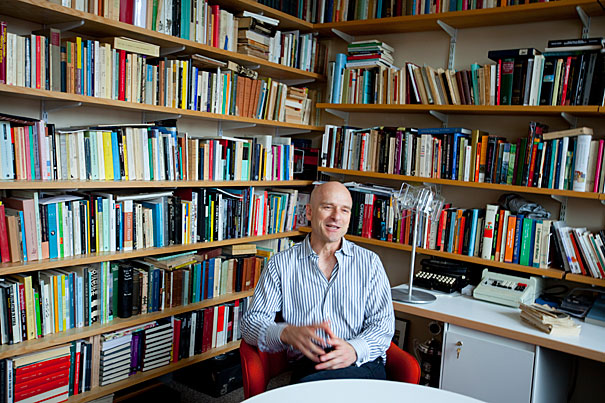

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Creating the digital humanities

Jeffrey Schnapp pulls together classic scholarship, Web accessibility

It might seem strange that the man who touts the high-tech advances of the digital age also loves a good rotary phone and medieval manuscript.

But for Jeffrey Schnapp, whose work and passion exist largely at the intersection of disparate worlds, the three complement each other perfectly.

A yellow, doughnut-shaped telephone from the 1950s sits in his airy Harvard office, a nod to kitsch and culture. Nearby are old typewriters from the early part of the 20th century and cumbersome calculating machines that he uses to maintain the tactile feel of an earlier era under his fingertips. Older still are the folios that litter the floor, unbound sections from a catalog of the Roman Cassinate library of 1725.

A pioneer in digital humanities, Schnapp considers the Internet a tool that can illuminate ephemera, that can unlock scholarly possibilities and connections between the physical and the virtual, the modern and the ancient, and that can help to forge dynamic new forms of scholarship in the humanities.

“With the emergence of the Web as the defining public space of our era, the preconditions have become available to think boldly about reshaping the arts and humanities fields in ways that permit the building of bigger pictures,” said Schnapp. “The Internet has the potential to bring scholarship out of the silos in which it tends to live into interdisciplinary, even societywide conversations.”

The professor of Romance languages and literatures works to harness that digital drive, and is developing a multichanneled approach to scholarship with metaLAB at Harvard, a new laboratory hosted at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society that weds technical innovation with scholarly experimentation. It also promotes the reinvigoration of traditional forms of scholarship through the use of new media and computational tools. Schnapp, who founded the lab last year, spearheaded a similar effort at Stanford University starting in 1999.

An example of a “bigger picture” taking shape at the new lab is the Digital Archive of Japan’s 2011 Disasters. In collaboration with Harvard’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, the lab is building a user interface that will link separate digital archives into a type of “active public space.” With public input, the archive aims to capture everything from images and print stories to text messages, websites, Twitter streams, and personal stories from the tragedies.

“It’s an extraordinary opportunity to enhance our ability to work with large archival corpora and to think about models of preservation and access that very specifically exploit the powers of the digital realm,” he said.

Schnapp’s interest in merging different fields is no accident. He is a Renaissance man. He speaks six languages fluently. He is a medieval Italian scholar, a designer, curator, and occasional computer programmer. He is also a former semi-professional motorcycle racer, a pursuit that left him with a host of trophies that occupy a corner of his office, along with “a rich collection of broken bones, the inescapable downside of participation in motor sports.”

In addition to his other duties, he is a fellow at the Berkman Center and a member of the teaching faculty at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

He developed his passion for languages while growing up in Mexico City, where his father was working. He graduated from Vassar College with a degree in Hispanic studies and a minor in studio art, and received a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Stanford University in 1983.

While investigating a position as director of the humanities center at the University of Washington, he was struck by the rich connections the school was developing between its humanities-based research centers and the city’s public institutions. The experience convinced him of the need to rethink the boundaries of academia.

“I realized we needed to reshape the public space as a place where forms of high-quality, cutting-edge scholarship could speak to audiences that will never buy a scholarly monograph, not to mention pick up a specialized journal and read an article.”

Ultimately, he brought that philosophy to Stanford and to the Stanford Humanities Lab, and to such innovative projects as the lab’s HyperCities, a prize-winning Web platform that virtually connects visitors to a city’s historical narratives. It was incubated at the Stanford Humanities Lab, and starting in 2004 further developed by Todd Presner and his team at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“It’s impossible to tell the legion of stories that make up an urban reality; there’s so many crisscrossing threads,” said Schnapp. “As scholars, we are always forced to choose a slice.”

But with HyperCities, visitors and scholars can have it all. Physical maps can be “layered historically” and used to organize materials involving the archaeological and architectural history of a city, the history of its people, its transportation grid, and its economy, all on one setting. The project “goes beyond the print-based model of scholarship, where we can tell those multiple stories and explore the places where they collide and crisscross.”

At Harvard, Schnapp sees his mission as that of a catalyst who “can bring a less risk-averse culture to the humanities, and a more experimental ethos that is actively engaged with the task of modeling what knowledge should look like in the 21st century.”

“What’s needed,” he said, “is a rethinking of the map of knowledge.”