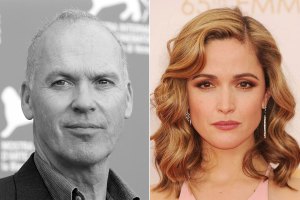

A copy image from Harvard Archives material of Harvard’s Centennial celebration in 1936. The painting is by Waldo Pierce, who earned his Harvard degree in 1909.

Photo courtesy of Harvard Archives

How Harvard celebrated

Previous anniversaries were set against the backdrop of their times

This fall Harvard will begin a yearlong celebration of its 375th anniversary. The focus will be on the future, and not the past — a feature of similar anniversaries going back to the first, in 1836. Yes, that’s right: Harvard waited until it was 200 years old to have a first birthday party, or to celebrate itself in any significant way.

After that, similar events — in 1886, 1936, and 1986 — were celebrated in scale with their perceived significance. As any student of anniversaries knows, the idea of 100 years trumps 50, which in turn outweighs anniversaries that track each 25 years. So the University’s grandest celebration years were 1836, 200 years after the founding of the College, and in 1936, the 300th anniversary.

But why nothing before 1836? No one seems to know for sure. Officials at the Harvard University Archives have scoured the earliest written records, which grow more scant the further back in time you go. The only likely reason for the 200 years of quietude is the notion that it’s hard to celebrate yourself if it’s hard to pay the bills. In the decades after its founding, Harvard was still a public college, dependent on the Massachusetts Bay Colony for its funding. In those same early days, donations to the college of an iron spoon or a pewter cup were worth recording.

Even 150 years after Harvard’s founding, in 1786, there is a mention only by negation. On that day, the President and Fellows voted to ban for “that occasion” — presumably the anniversary — any “illumination, bonfire, or fireworks, or any other mode of rejoicing … by which they might be led into unnecessary expense at this difficult time.”

There is an irony in this denial, said Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, director of the Harvard Archives, and a member of a University committee planning the 375th anniversary. Every big Harvard anniversary after 1786 — in 1836, 1886, 1936, and 1986 — included some tradition of illumination.

In 1836, writer Caroline Gilman noted the “brilliant lights abroad” on the evening of Sept. 8, the day of the College’s first grand celebration of itself. And the Harvard Archives has the original plans for illuminating each window of Holworthy Hall. In the center windows was an oversized “200.” Other windows were patterned with lights in the shape of diamonds, stars, and pyramids.

In 1876, the 250th anniversary, a four-day party included wagons packed with fireworks making their way up Quincy Street and gates lit with globes of fire, nighttime cannonades of rockets, and a two-hour torchlight parade by undergraduates, some of them dressed as early Puritans.

In 1936, Harvard’s riverfront was lit with electric lights, while out in the Charles River barges sent up a stream of rockets and fireworks. In 1986, Harvard Stadium was the setting for a great fireworks display. For the coming 375th, there are plans to illuminate Harvard Yard in distinctly modern and high-tech ways.

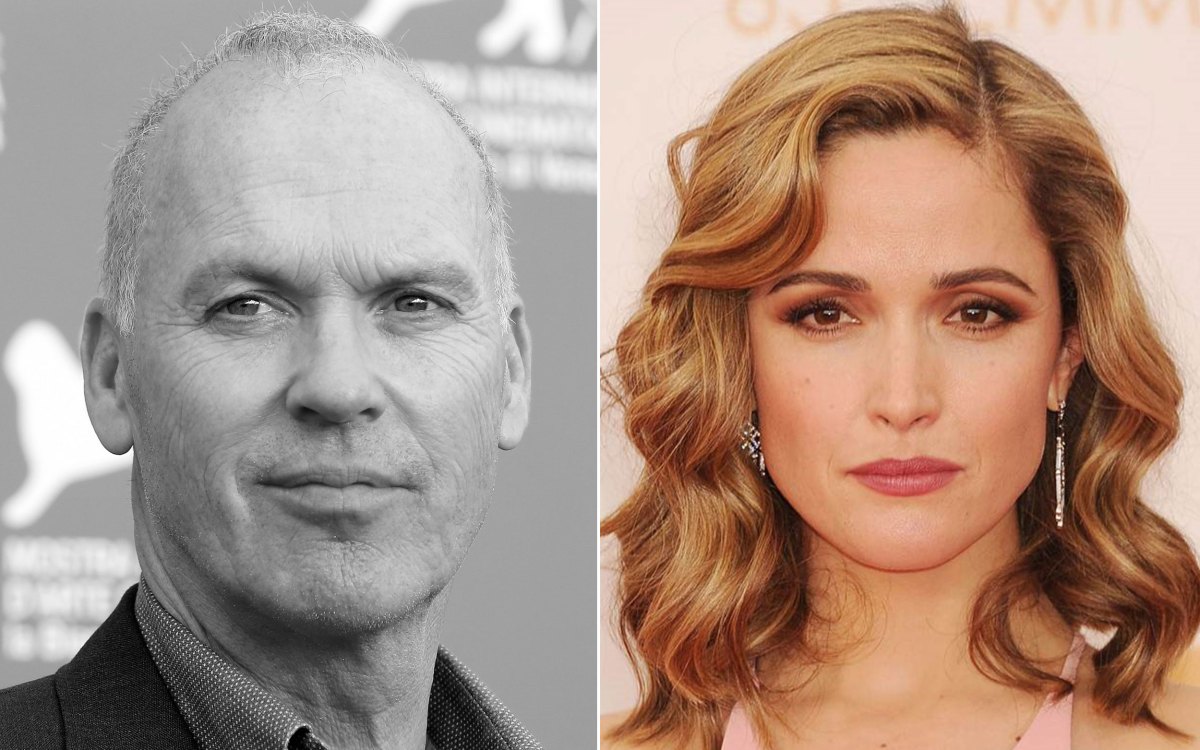

Everything about the ’36 celebration was on a grand scale, and represented “a seismic shift in institutional weight and presence,” wrote historian Morton Keller, Ph.D. ’56, who co-authored “Making Harvard Modern” (2001) with his wife Phyllis. The celebration lasted 10 months, not one day as in 1836. Hundreds of letters poured in from kings, queens, countries, and other universities. That summer, 70,000 visitors toured Harvard Yard, and a Sept. 17 light show on the Charles River drew 300,000 viewers. The convocation itself was preceded by two weeks of scholarly symposia in the arts and sciences. (Three sizable volumes followed from Harvard University Press.)

For the final day, Sept. 18, about 15,000 guests were on hand, including 10,000 alumni. In a kind of apex of star power, the featured speaker was U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who sat gamely through heavy rains.

By contrast, the 1986 celebration of 350 years was more of a happening, according to Keller. In place of the celebration of history in 1836, and the intellectual tone of 1936 was more a celebration of Harvard’s cultural and intellectual diversity.

The solemn weeks of symposia that marked 1936 were replaced by what Keller called “a vast academic flea market” of 106 symposia, including events on AIDS, smoking, and the beginning of the universe. The final event of the 350th was a sound and light show at Harvard Stadium, produced by the same man whose light show had opened Disney World in Florida. There was a four-and-a-half-hour “floating birthday party” on the Charles, complete with fireworks and helium-filled arches spanning the river.