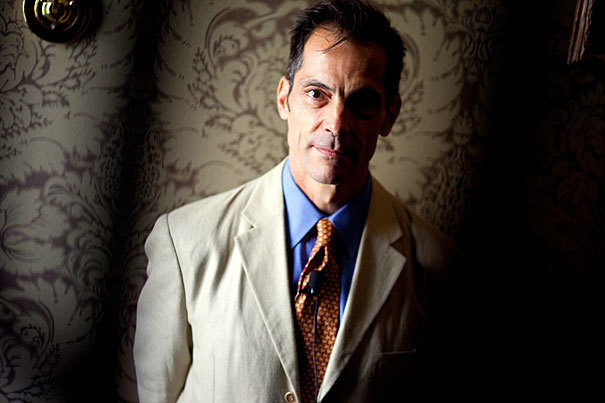

Harvard Professor John Stauffer, who studies antislavery movements, the Civil War, and American social protest, says that black Confederate soldiers likely represented less than 1 percent of Southern black men of military age during that period, and less than 1 percent of Confederate soldiers.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Black Confederates

Their numbers in Civil War were small, but have symbolic value

Even 150 years after it started, the Civil War is still the battleground for controversial ideas. One of them is the notion that thousands of Southern slaves and freedmen fought willingly and loyally on the side of the Confederacy.

The idea of “black Confederates” appeals to present-day neo-Confederates, who are eager to find ways to defend the principles of the Confederate States of America. They say the Civil War was about states’ rights, and they wish to minimize the role of slavery in a vanished and romantic antebellum South.

But most historians of the past 50 years hold that the root cause of the Civil War was slavery. They bristle at the idea of black Confederates, which they say robs the war of its moral coin as the crucible of black emancipation.

Stepping into this controversy is Harvard historian John Stauffer, who studies antislavery movements, the Civil War, and American social protest. (He is chair of the History of American Civilization Program, and a professor of both English and African-American studies.) At the Harvard Faculty Club on Wednesday (Aug. 31), Stauffer opened the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute’s Fall Colloquium Series with a lecture on black Confederates. He acknowledged that critics of the concept now dominate the academic arena, including one scholar who called it “a fiction, a myth, utter nonsense.”

Still, Stauffer acknowledged the seeming popularity of neo-Confederate ideas in general. He cited a recent poll showing that 70 percent of white Southerners believe that the cause of the Civil War was not slavery, but a deep divide over states’ rights. Stauffer also outlined evidence that the notion of black Confederates is at least partly true — an assertion that he said got him “beaten up” in a discussion at a Washington, D.C., history event months ago.

Though no one knows for sure, the number of slaves who fought and labored for the South was modest, estimated Stauffer. Blacks who shouldered arms for the Confederacy numbered more than 3,000 but fewer than 10,000, he said, among the hundreds of thousands of whites who served. Black laborers for the cause numbered from 20,000 to 50,000.

Those are not big numbers, said Stauffer. Black Confederate soldiers likely represented less than 1 percent of Southern black men of military age during that period, and less than 1 percent of Confederate soldiers. And their motivation for serving isn’t taken into account by the numbers, since some may have been forced into service, and others may have seen fighting as a way out of privation. But even those small numbers of black soldiers carry immense symbolic meaning for neo-Confederates, who are pressing their case for the central idea that the South was a bastion of states’ rights and not a viper pit of slavery, even though slavery was central to its economy.

Just 50 years ago, many authorities on the Civil War asserted that Southerners knew at the time that slavery was wrong, and would soon give it up. Stauffer quoted Robert Penn Warren, who wrote in 1961 that “the greatest danger to slavery was the Southern heart.”

In arguing that there were some black Confederates, Stauffer draws on at least one ironic source: 19th-century social reformer Frederick Douglass, whose life Stauffer studied for his 2008 book “Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.” In August 1861, Douglass published an account of the First Battle of Bull Run, which noted that there were blacks in the Confederate ranks. A few weeks later, Douglass brought the subject up again, quoting a witness to the battle who said they saw black Confederates “with muskets on their shoulders and bullets in their pockets.”

Douglass also talked to a fugitive slave from Virginia, another witness to Bull Run, who asserted that black units were forming in Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia. It is well known that in Louisiana and Tennessee, Stauffer added, Confederate units were organized by elite, light-skinned freedmen who identified with the slave-owning white plantation culture. (The Tennessee troops were never issued arms, though, and the black unit known as the Louisiana Native Guards never saw action — and quickly switched sides as soon as Union forces appeared.)

But unless readers think that black Confederates were truly enamored of the South’s cause, Stauffer related the case of John Parker, a slave forced to build Confederate barricades and later to join the crew of a cannon firing grapeshot at Union troops at the First Battle of Bull Run. All the while, recalled Parker, he worried about dying, prayed for a Union victory, and dreamed of escaping to the other side.

“His case can be seen as representative,” said Stauffer. “Masters put guns to (the heads of slaves) to make them shoot Yankees.”

Freedmen in the Confederacy faced re-enslavement in Virginia and elsewhere, said Stauffer, so they made displays of loyalty that were really gestures of self-protection — a “hope for better treatment, a hope not to be enslaved.”

Loyalty among the few black Confederates was at least ambiguous, said Stauffer. It was further undermined by the Confiscation Act of Aug. 6, 1861, which allowed Union forces to “confiscate” slaves and other “property” used to support the Confederacy. Under the act — the first of two — the freedom of such slaves was left ambiguous, said Stauffer, but it foreshadowed black emancipation and gave slaves even more reason to flee northward.

Scholars and social critics will continue to fight over the concept of black Confederates. Meanwhile, what should the public believe about the conflicting loyalties they may have felt or the decisions — however brief — some made to serve the Confederacy?

From the lecture audience, Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, had one answer: “Black people are just as complex as anybody else.”