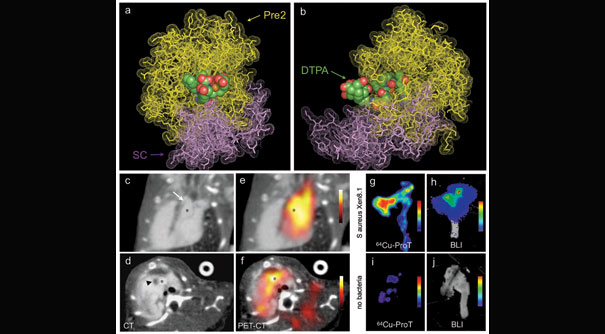

In this PET-CT image of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis, images A and B show a molecular model of how the PET reporter (orange structure with colored spheres) binds to the target, the bacterial enzyme staphylocoagulase (violet). Image B is rotated 90 degrees relative to image A. CT (images C and D) and PET-CT (images E and F) show the location of the radiolabeled prothrombin in vegetations around the aortic valve of a mouse heart. Images G-I show location of the PET agent in aortas of mice with (G-H) and without (I-J) S. aureus endocarditis.

Image courtesy of Nature Medicine and the MGH Center for Systems Biology

Detecting heart-valve infection

Noninvasive imaging probe reveals presence of S. aureus endocarditis

A novel imaging probe developed by a Harvard-led team of investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) may make it possible to accurately diagnose a dangerous infection of the heart valves. In a Nature Medicine report, which is receiving advance online publication, the team from the MGH Center for Systems Biology describes how the presence of Staphylococcus aureus-associated endocarditis in a mouse model was revealed by PET imaging with a radiolabeled version of a protein involved in a process that usually conceals infecting bacteria from the immune system.

“Our probe was able to sense whether S. aureus was present in abnormal growths that hinder the normal function of heart valves,” says Matthias Nahrendorf of the MGH Center for Systems Biology, a co-lead author of the study. “It has been very difficult to identify the bacteria involved in endocarditis, but a precise diagnosis is important to steering well-adjusted antibiotic therapy.”

An infection of the tissue lining the heart valves, endocarditis is characterized by growths called vegetations made up of clotting components such as platelets and fibrin along with infecting microorganisms. Endocarditis caused by S. aureus is the most dangerous, with a mortality rate of from 25 to almost 50 percent, but diagnosis can be difficult because symptoms such as fever and heart murmur are vague, and blood tests may not detect the involved bacteria. Without appropriate antibiotic therapy, S. aureus endocarditis can progress rapidly, damaging or destroying heart valves.

S. aureus bacteria initiate the growth of vegetations by secreting staphylocoagulase, an enzyme that sets off the clotting cascade. This process involves a protein called prothrombin, which is part of a pathway leading to the deposition of fibrin, a primary component of blood clots. The clotting process enlarges the vegetation, anchors it to the heart valve, and serves to conceal the bacteria from immune cells in the bloodstream.

To develop an imaging-based approach to diagnosing S. aureus endocarditis, the MGH team first investigated the molecular mechanism by which staphylocoagulase sets off the clotting cascade, finding that one staphylocoagulase molecule interacts with at least four molecules of fibrin or its predecessor molecule fibrinogen in a complex that binds to a growing vegetation. Because prothrombin is an essential intermediary in the staphylocoagulase/fibrin interaction, the researchers investigated whether labeled versions of prothrombin could accurately detect S. aureus endocarditis in mice.

After initial experiments confirmed that an optical imaging technology called FMT-CT could detect a fluorescence-labeled version of prothombin deposited into S. aureus-induced vegetations, the researchers showed that a radiolabeled version of prothombin enabled the detection of S. aureus vegetations with combined PET-CT imaging, an approach that could be used in human patients after additional development and FDA approval.

“An approach like this could help clinicians detect the presence of endocarditis, determine its severity and whether it is caused by S. aureus, and track the effectiveness of antibiotics or other treatments,” says Nahrendorf, also a co-corresponding author of the Nature Medicine article and an assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. “We are working to improve the PET reporter probe with streamlined chemistry and a more mainstream PET isotope to make it a better candidate for eventual testing in patients.”

Peter Panizzi of the Harrison School of Pharmacy at Auburn University is co-lead author of the Nature Medicine paper; and Ralph Weissleder, director of the MGH Center for Systems Biology and a Harvard Medical School professor of systems biology and radiology, is senior and co-corresponding author.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health.