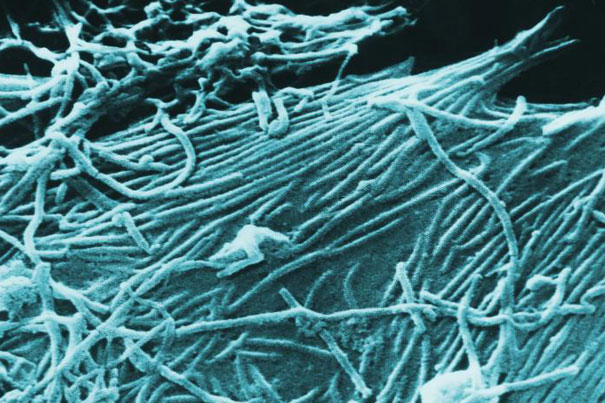

An image depicting a number of Ebola virions. Work by a Harvard-led research team “improves the chances that drugs can be developed that directly combat Ebola infections,” said Sean Whelan of Harvard Medical School.

Photo by Cynthia Goldsmith/CDC

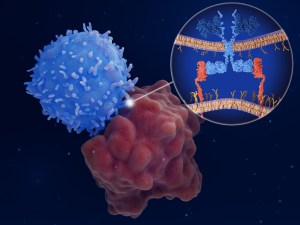

Attacking Ebola

Protein essential for virus infection is a promising target

In separate papers published online in Nature, two research teams report identifying a critical protein that Ebola virus exploits to cause deadly infections. The protein target is an essential element through which the virus enters living cells to cause disease.

The first study was led by four senior scientists: Sean Whelan, associate professor of microbiology and immunobiology at Harvard Medical School (HMS); Kartik Chandran, assistant professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine; John Dye at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID); and Thijn Brummelkamp, originally at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and now at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. The second study was led by James Cunningham, an HMS associate professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and co-authored by Chandran.

“This research identifies a critical cellular protein that the Ebola virus needs to cause infection and disease,” explained Whelan, who is also co-director of the HMS Program in Virology. “The discovery also improves chances that drugs can be developed that directly combat Ebola infections.”

Both papers are in the Aug. 24 online issue of Nature.

The African Ebola virus — and its cousin, Marburg virus — are known as the filoviruses. Ebola was first identified in 1976 in Africa near the Ebola River, an area in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Infections cause severe hemorrhage, organ failure, and death. No one quite knows how the virus is spread, and there are no available vaccines or antiviral drugs that can fight the infections.

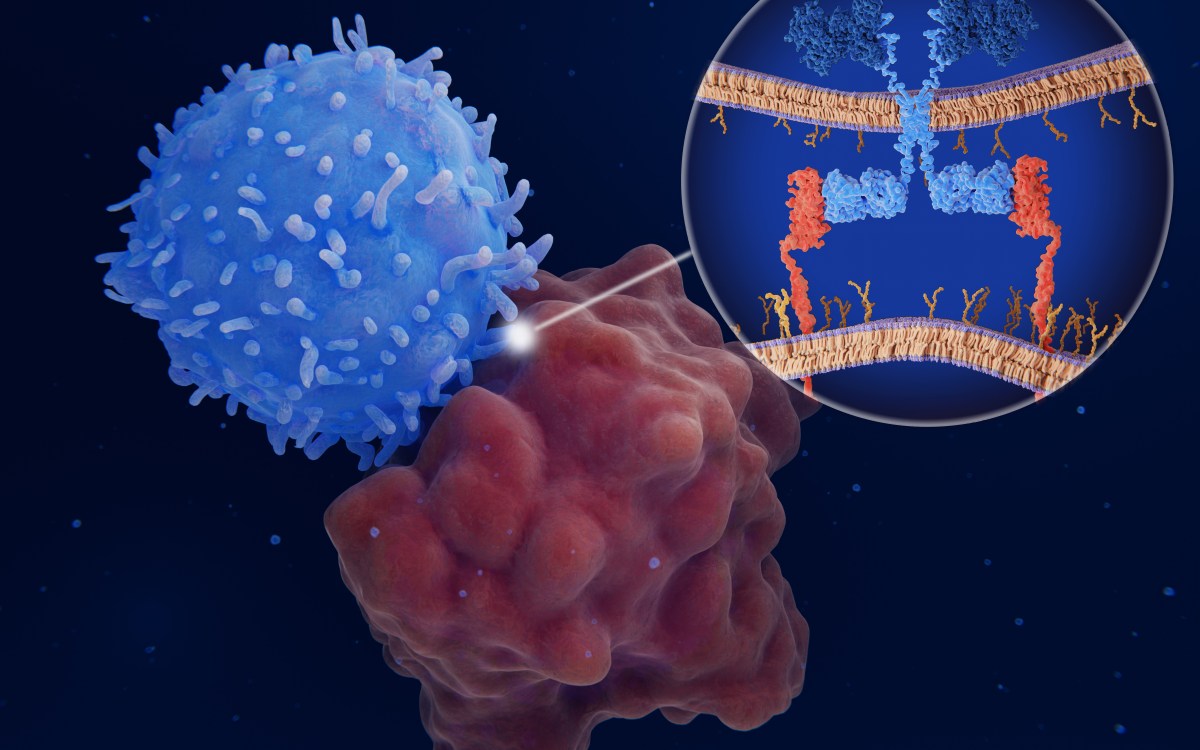

Through a genomewide genetic screen in human cells aimed at identifying molecules essential for Ebola’s virulence, Whelan and his colleagues homed in on Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1).

Primarily associated with cholesterol metabolism, NPC1, when mutated, causes a rare genetic disorder in children, Niemann-Pick disease.

Using cells derived from these patients, the researchers found that this mutant form of NPC1 also completely blocks infection by the Ebola virus. They also demonstrated that mice carrying a mutation in the NPC1 gene resisted Ebola infection. Similar resistance was found in cultured cells in which the normal molecular structure of the Niemann-Pick protein has been altered.

In other words, targeting NPC1 has real therapeutic potential. While such a treatment may also block the cholesterol transport pathway, short-term treatment would likely be tolerated.

Indeed, in the accompanying paper, Cunningham’s group describes such a potential inhibitor.

Cunningham and his group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital investigated Ebola by using a robotic method developed by their colleagues at the National Small Molecule Screening Laboratory at HMS to screen tens of thousands of compounds. The team identified a novel small molecule that inhibits Ebola virus entry into cells by more than 99 percent.

The team then used the inhibitor as a probe to investigate the Ebola infection pathway and found that the inhibitor targeted NPC1.

For Cunningham and Chandran, this finding builds on a 2005 paper of theirs for which Whelan was also a collaborator. In that study, researchers discovered how Ebola exploits a protein called cathepsin B. This new study completes the puzzle. It now seems that cathepsin B interacts with Ebola in a way that preps it to subsequently bind with NPC1.

“It is interesting that NPC1 is critical for the uptake of cholesterol into cells, which is an indication of how the virus exploits normal cell processes to grow and spread,” said Cunningham. “Small molecules that target NPC1 and inhibit Ebola virus infection have the potential to be developed into antiviral drugs.”

The paper co-authored by Whelan was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Human Genome Research Institute, the U.S. Army, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Cunningham’s work was funded by the New England Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases at Harvard Medical School.