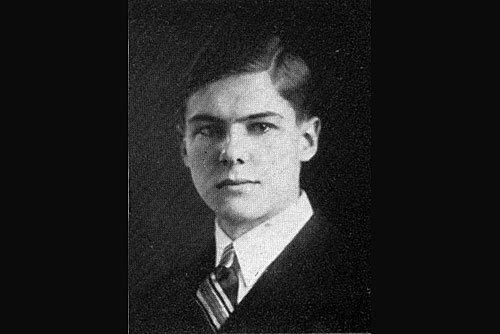

Donald Brown (pictured), age 102, graduated from Harvard College in 1930. He was the oldest alumnus at Commencement this year, beating George Barner ’29 by a month. Brown earned an A.M. in 1935 and a Ph.D. in 1955.

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

The way we were

Harvard grad, 102, recalls simpler time, different campus

Tercentenary Theatre was still noisy and crowded on Commencement Day when Harvard graduate Donald Freeman Brown decided to take a walk around campus. Behind University Hall, he listened to the Harvard University Band and stood in line to swing a felt-tip mallet at Bertha, the 8-foot-wide bass drum.

Like many graduates, Brown has been talking about little except Commencement ever since. But his perspective is longer — a lot longer. Brown, age 102, graduated from the College in 1930. He was the oldest alumnus at Commencement this year, beating George Barner ’29 by a month.

Brown was a junior in the fall of 1928 when the first Bertha was rolled out onto the field at Harvard Stadium. “He remembers it well,” said his daughter, Dorcas Brown Sefton, who was with him at the May 26 Commencement, along with her brother, Christopher Brown, and sister, Alyson Toole. “He was very pleased to give it a whack.”

As an undergraduate, Brown was a cellist in what was then called the Harvard University Orchestra. That was so long ago that legendary composer and bandleader John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) was a guest conductor.

Other temporal shocks arrive with the idea that Brown graduated 81 years ago. When he was in College, the “new” Fogg Art Museum had just been built. The Malkin Athletic Center had just opened. Dunster House tower was shrouded in scaffolding. And the Memorial Church was still a gleam in a planner’s eye. The student clubs of those days had names since lost to history, including Iroquois, Kex, Falcon, Pi Eta, and Phike.

Brown attended Amherst College first, but said he was thrown out after his freshman year for flunking Greek, despite perfect grades otherwise. After a year at Boston University, he transferred to Harvard. When he graduated, Brown said he ran into the professor who had failed him three years earlier. “I was polite,” he said.

The then-controversial House Plan was just getting under way when Brown enrolled, so he lived with his widowed mother in apartments on Bow and Ellery streets. They ate meals out, went to the symphony (Brown bought a secondhand morning coat), and hosted Thursday night dinner parties — often for Chinese and Japanese students who were starting to arrive at Harvard in greater numbers.

He sang baritone with the Glee Club and joined the Liberal Club, though he and his friends were “dubious” about the young Soviet Union. Brown studied psychology, and remembers a graduate student named B.F. Skinner walking briskly through Harvard Yard, his briefcase swinging, his fame as a psychologist still far in the future.

More than 80 years after his last class at the College, Brown is still hesitant to name a favorite professor. “It doesn’t seem quite fair,” he said, sitting in the shade of a lunch tent on Commencement Day. “They all seemed important to me.”

In October of his senior year, the stock market crashed, and the Great Depression opened like a chasm. Still, Brown got a job right after graduation, though it was an unlikely one — as a Harvard career counselor. “I thought it was [about] job hunting,” said Brown, who stayed for five years. “But there weren’t any jobs. Very simple.”

By then psychology had lost his charm, and Brown continued on to Harvard graduate study in anthropology and archaeology. “I thought: Gosh, why am I interested in psychology?” he said. “I like to dig.”

Brown went on to a long career in archaeology and in 1939 was a founding member of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. At Commencement, slender and bespectacled, he wore a modest black suit, a Harvard tie, and a ball cap with the legend “My life is in ruins.”

Brown earned an A.M. in 1935 and a Ph.D. in 1955. Why the long interval? “He was busy changing diapers,” said Dorcas. Brown and his wife, Linda Easton Smith Brown, who died in 1986, raised four daughters and two sons. The couple was quite a hit at the 25th class reunion in 1955, since they were still having children.

During three years of Army service in World War II, Brown was harnessed to a typewriter in North Africa and Italy. Both places allowed him his first inspiring looks at ancient ruins, but his deep interest came much earlier. As a boy in Springfield, Mass., he was drawn to tales of the lost continent of Atlantis — “alas, mythical,” he wrote later. But true epiphany came when the young Brown read about the dancing horses of Sybaris in James Baldwin’s 1911 classic “The Wonder-Book of Horses,” a volume still on a shelf in the family’s rambling 1686 house in Stow, Mass.

Founded in the eighth century B.C.E., Sybaris was not mythical — and Brown was the archaeologist who found it 25 centuries after it was lost to history.

The coastal colony of ancient Greece, in what is now southeastern Italy, was famed for its wealth and its sense of civic pleasure and ease. (Hence the word “sybaritic.”) Among city amenities was a system for piping in wine from the countryside. But Sybarite cavalry horses were taught to dance to pipe music — or so the legend goes — and proved useless in a decisive 510 B.C.E. battle, when Croton warriors salted their ranks with pipers. The city was razed, then “lost” until 1950.

Brown, who had moved to Italy with his new bride in 1948, devised a way of finding it. Armed with old maps that his wife had found in an Italian flea market, he narrowed the location down. Then he hired well diggers to sink bore holes so he could search core samples for telltale shards. It was a radical departure from accepted archaeological technique, which involved digging shallow lateral trenches. For his work, Brown won the prestigious Rome Prize in both 1952 and 1953. But a later search for Sybaris failed to credit him. “I am bitter,” he admitted.

From 1955 to 1965, Brown was assistant curator of European pre-history at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. He then taught anthropology at Boston University, before retiring in 1974.

For years after that, Brown — “Dondo” to his children — listened to classical music and canoed in the Connecticut River. He enjoyed nature walks, photography, and the Lionel trains he acquired as a boy. Brown gave up driving at 97, and is only now slowing down. Life is a round of senior lunches, careful walks, and day trips.

“We’ve had an 80th birthday party, a 90th, and a 100th,” said Dorcas. “Now we have a big party every year.”