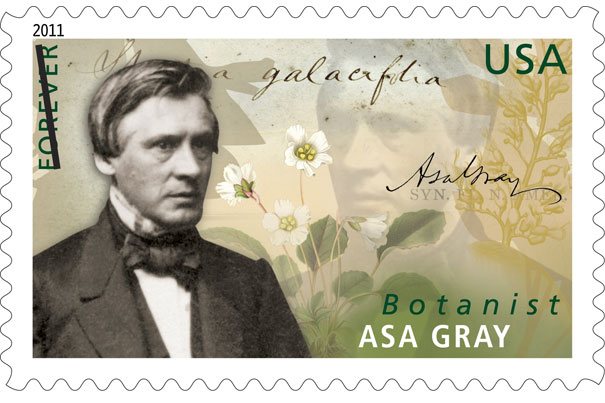

Asa Gray spent a long and fruitful career at Harvard, describing many new species of plants and amassing collections that are housed today in the Harvard Herbaria. The Asa Gray stamp was unveiled at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Gray gets stamp of approval

Postal Service honors Harvard’s famed ‘closet botanist’

Legendary Harvard botanist Asa Gray will finally be traveling America regularly, courtesy of the U.S. Postal Service.

The Postal Service is honoring Gray, considered the father of American botany, with a first-class stamp, which was officially unveiled Wednesday (June 29) during a ceremony at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Gray spent a long and fruitful career at Harvard, describing many new species of plants and amassing collections that are housed today in the Harvard Herbaria. Though Gray traveled to Europe early in his career, making connections with prominent European naturalists, he didn’t get around the United States much until late in his career, according to Donald Pfister, the Asa Gray Professor of Systematic Botany. Pfister, along with Cambridge Postmaster Katherine Lydon and Gray biographer A. Hunter Dupree, unveiled the stamp.

Instead of traveling in person, Pfister said, Gray traveled through his collections. Though he did some collecting himself, mainly in the eastern United States, he examined and described many plants collected by expeditions elsewhere. Pfister said he found it astonishing that the man who described so many new American species didn’t travel west of the Mississippi River until 1872, when he was 62.

Gray himself was aware of the seeming contradiction, Pfister said, reading a passage written by Gray. “Although I have cultivated the field of North American botany … for more than 40 years … yet so far as our own wide country is concerned, I have been to a great extent a closet botanist,” Gray wrote.

Though it came late, the trip west proved meaningful, and he described in his journals the thrill of seeing live specimens of the plants that he only knew through dried collections.

Gray was among four figures honored by the Postal Service in its third American Scientist stamp issuance. The stamps, which went on sale June 16, include chemist Melvin Calvin, physicist Maria Goeppert Mayer, and biochemist Severo Ochoa.

Wednesday’s ceremony included a tour of the Ware Collection of Glass Flowers, which includes examples of several specimens described by Gray.

Gray’s influence extended to the fledgling concept of evolution. He was an early proponent of the theory and corresponded regularly with its champion, Charles Darwin. In his work, Gray noticed correlations between plants and geographic regions in which they grew, coming to believe that the story of a region’s past could be read in its plants.

The first-class “forever” stamp shows Gray and an image of a plant that he pursued for much of his life, Shortia galacifolia. The plant, native to the Carolinas, was described by Gray and John Torrey from a partial specimen found in a museum in Paris. Gray would search for 40 years for a living specimen, until in 1877 a North Carolina youth sent him one, causing Gray to shout, “Eureka!”