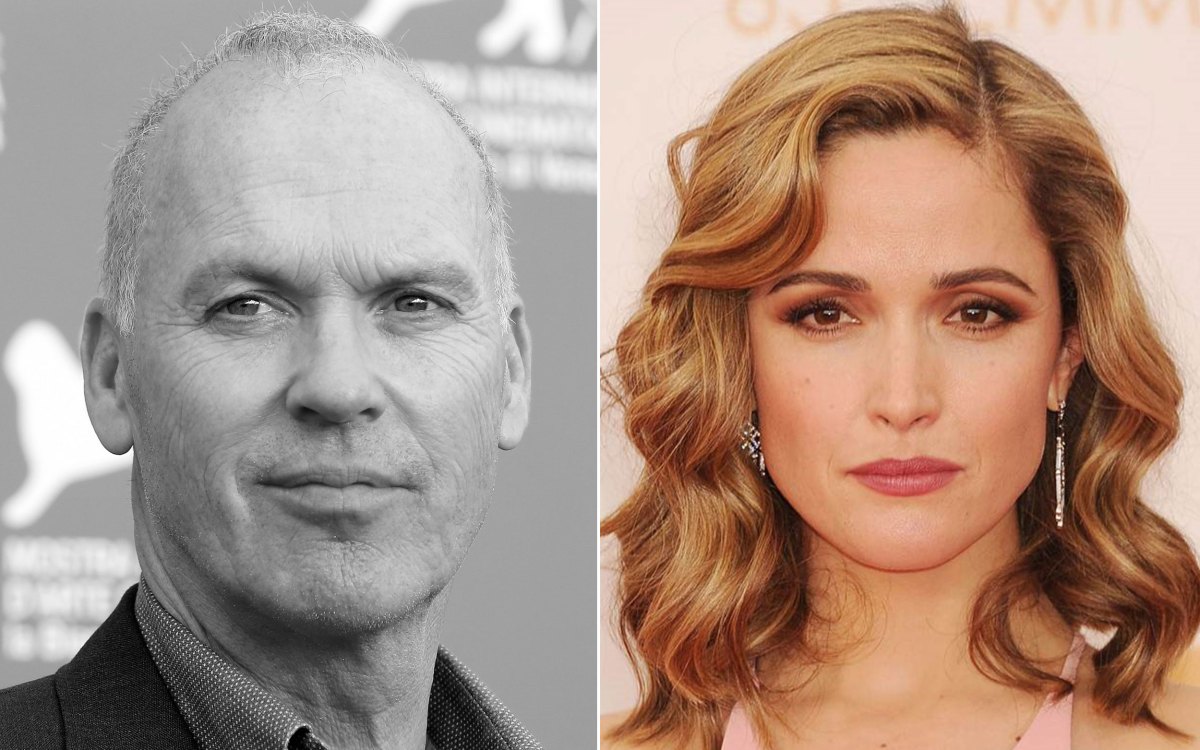

“Real doctors treat more than one species,” said Mark Schembri, a veterinarian who is now graduating from the Harvard School of Public Health.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

All creatures great and small

Equine specialist will use public health master’s to aid animals, humans

Editor’s note: This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

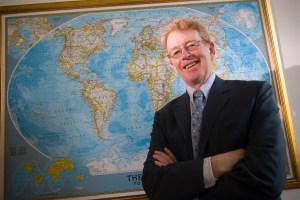

When he first arrived at Harvard, curious students often asked Mark Schembri, “So why are you actually here?”

It was a fair question. For those who enroll at the Harvard School of Public Health, the human population is typically their prime focus. Not so for Schembri. But the thought of being a veterinarian in a program largely filled with medical doctors didn’t stop the Australian horse specialist from coming to Harvard to pursue his master’s in public health.

His response to the skeptics: “Real doctors treat more than one species.”

Schembri has spent the past year at Harvard studying zoonotic diseases, infections and viruses that can be transferred from animals to humans, such as bird and swine flu, rabies, and mad cow disease. Understanding how humans approach such pandemics, said Schembri, can inform responses to outbreaks in animal populations, and even lead to better prevention techniques.

Schembri knows how devastating infectious diseases can be. In 2007 he watched equine influenza wreak havoc with his nation’s thoroughbred population. The experience inspired him to target such issues, and he set his sights on Harvard with the help of a General Sir John Monash Scholarship, the Australian equivalent of a Rhodes or Fulbright Scholarship.

“Harvard leads the word in dealing with infectious-disease outbreaks; whether it’s cholera in Haiti or bioterrorism in New York, Harvard plays a role. I wanted to learn from one of the greatest of universities how to approach these.”

In one class, while his fellow students focused on areas such as HIV, Schembri turned his attention to caprine arthritis encephalitis, a viral infection in goats that can lead to encephalitis in children and chronic joint disease in adults.

As it turns out, both viruses share an almost identical viral genome.

Throughout his research, he also found that veterinarians and doctors share views on areas like vaccinations, surveillance techniques, and the general concern for infectious-disease outbreaks.

“The same principles can be used in both humans and animals, and vice versa. The study here is truly interdisciplinary.”

He also learned much from his doctor counterparts.

“It is incredibly humbling to study with such gifted faculty and fellow students. That would be my number one experience here at Harvard, just meeting someone who is magnificent and saying, ‘talk to me,’ ‘teach me,’ and ‘let me be part of it.’”

Schembri developed his interest in horses early on, regularly visiting his father’s racehorses as a boy. He briefly lived in Rome as a child and while there developed a second lifelong passion for music. While studying to become an equine specialist at the University of Sydney, he took a music conductors course on the side. He frequently conducts orchestras in Sydney.

At Harvard, when he wasn’t hitting the books, he happily combined his two loves. During the year he worked as a nonresident music tutor in Kirkland House, helping to organize concerts and music events. He also volunteered as the Harvard Polo Club’s vet, taking care of its polo ponies and exercising the animals when students were busy with exams.

Although he could have gotten his degree over the course of three summers, Schembri chose to take a year to complete his master’s to fully immerse himself in Harvard. Though he had never rowed before, he became an oarsman for Dudley House. Instead of living closer to the School’s Longwood Medical Area in Boston, he chose to commute into Boston each day for classes so he could reside in Perkins Hall on Harvard’s Cambridge campus.

“People perceive it as the best learning institution in the world, and I won’t deny that from the experience that I have had,” said Schembri, who is considering returning to Harvard at some point to pursue a doctoral degree in environmental or global health.

“I love it here.”