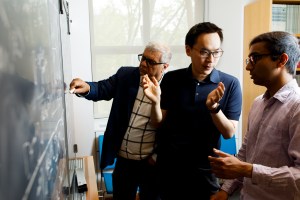

Arnold Arboretum Director William “Ned” Friedman said scientific discovery requires more than just an idea: “Darwin had the ability to convince others of the correctness of the idea.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

What made Darwin first

Evolution’s revolution was the naturalist’s, though initial idea wasn’t

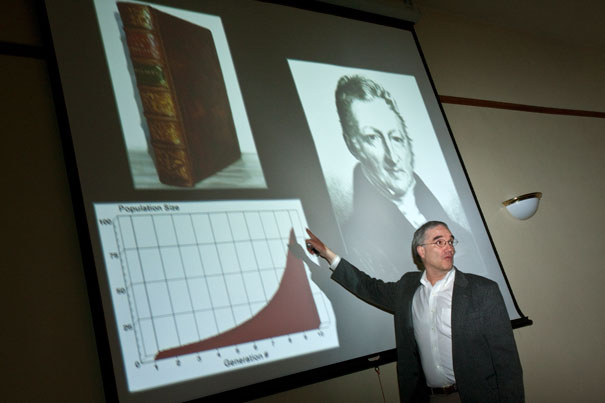

Naturalist Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” is credited with sparking evolution’s revolution in scientific thought, but many observers had pondered evolution before him. It was understanding the idea’s significance and selling it to the public that made Darwin great, according to the Arnold Arboretum’s new director.

William “Ned” Friedman, the Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology who took over as arboretum director Jan. 1, has studied Darwin’s writings as well as those of his predecessors and contemporaries. While Darwin is widely credited as the father of evolution, Friedman said the “historical sketch” that Darwin attached to later printings of his masterpiece was intended to mollify those who demanded credit for their own, earlier ideas.

The historical sketch grew with each subsequent printing, Friedman told an audience Monday (Jan. 10), until, by the 6th edition, 34 authors were mentioned in it. Scholars now believe that somewhere between 50 and 60 authors had beaten Darwin in their writings about evolution. Included was Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, a physician who irritated clergymen with his insistence that life arose from lower forms, specifically mollusks.

Friedman’s talk, “A Darwinian Look at Darwin’s Evolutionist Ancestors,” took place at the arboretum’s Hunnewell Building and was the first in a new Director’s Lecture Series.

Though others had clearly pondered evolution before Darwin, he wasn’t without originality. Friedman said that Darwin’s thinking on natural selection as the mechanism of evolution was shared by few, most prominently Alfred Wallace, whose writing on the subject after years in the field spurred Darwin’s writing of “On the Origin of Species.” Although the book runs more than 400 pages, Friedman said it was never the book on evolution and natural selection that Darwin intended. In 1856, three years before the book was published, he began work on a detailed tome on natural selection that wouldn’t see publication until 1975.

The seminal event in creating “On the Origin of Species” occurred in 1858, Friedman said, when Wallace wrote Darwin detailing Wallace’s ideas of evolution by natural selection. The arrival of Wallace’s ideas galvanized Darwin into writing “On the Origin of Species” as an “abstract” of the ideas he was painstakingly laying out in the larger work.

This was a lucky break for Darwin, Friedman said, because it forced him to write his ideas in plain language, which led to a book that was not only revolutionary, despite those who’d tread similar ground before, but that was also very readable.

Though others thought about evolution before Darwin, Friedman said scientific discovery requires more than just an idea. In addition to the concept, discovery requires the understanding of the significance of the idea, something some of the earlier authors clearly did not have — such as the arborist who buried his thoughts on natural selection in the appendix of a book on naval timber. Lastly, Friedman said, scientific discovery demands the ability to convince others of the correctness of an idea. Darwin, through “On the Origin of Species,” was the only thinker of the time who had all three of those traits, Friedman said.

“Darwin had the ability to convince others of the correctness of the idea,” Friedman said, adding that even Wallace, whose claim to new thinking on evolution and natural selection was stronger than all the others, paid homage to Darwin by titling his 1889 book on the subject, “Darwinism.”