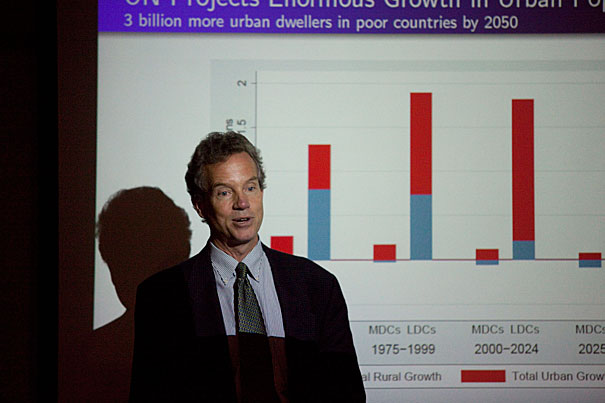

Because of a lack of investment in infrastructure, the developing world is already vulnerable to effects that climate change is expected to make worse, Mark Montgomery told his audience at Harvard’s Center for Population and Development Studies. The professor of economics from Stony Brook University used last summer’s flooding in Pakistan, which left millions of people homeless and destroyed bridges, homes, schools, and hospitals, as an example.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Poor prospects

Cities in developing world stand to suffer most from global warming

Small and midsize cities in poor countries will be among those that suffer most from climate change’s droughts, floods, landslides, and rising waters, an expert on the world’s urban poor said Monday (Dec. 13).

Experts expect the world population to rise from 6.8 billion to roughly 9 billion by midcentury, with much of the growth — and hence most of the suffering from the effects of climate change — happening in smaller cities scattered throughout the developing world rather than megacities such as Mumbai, said Mark Montgomery, an economics professor at Stony Brook University.

A big challenge facing researchers and government officials, however, is that almost nothing is known about these cities, Montgomery said. That is a critical gap because to be effective, mitigation strategies have to be evidence based, so that improvements and protections are made where people are most vulnerable.

“Urban adaptation strategies have to be spatially specific and evidence based,” Montgomery said. “Somehow, in some way, evidence will have to be brought to bear in finding solutions.”

Montgomery and researchers like him are beginning to focus their attention on these municipalities. Their efforts, however, are hampered by a lack of government data. Data on migration — thought to be a major factor in urban growth — is almost entirely lacking, while other demographic information is also scarce. Even the definition of a city varies from place to place, making comparisons challenging. Some data is collected on the city proper, some on the city and surrounding, dependent communities, and some on larger metropolitan areas.

Montgomery spoke Monday at Harvard’s Center for Population and Development Studies in Cambridge. His talk, “The Consequences of Climate Change for City Dwellers of Poor Countries,” was introduced by Center Director Lisa Berkman, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and of Epidemiology in the Harvard School of Public Health.

Berkman said that population researchers often study the effects of human populations on the natural world, but few examine the impact of the natural world on humans, as Montgomery does.

Because of a lack of investment in infrastructure, the developing world is already vulnerable to effects that climate change is expected to make worse, Montgomery said. He used last summer’s flooding in Pakistan, which left millions of people homeless and destroyed bridges, homes, schools, and hospitals, as an example.

“We don’t need to engage in a ‘what if’ [scenario] where extreme weather is involved,” Mongtomery said.

Climate change, Montgomery said, highlights the inferiority of poorer cities’ infrastructure compared with that of the industrialized world, where governments have money to strengthen seawalls, improve sewage treatment plants, and upgrade emergency services.

Montgomery said that scientists in geophysical specialties have taken the lead in examining the threat from climate change. Health and social scientists have been largely absent from the debate, even though they potentially have much to add, he said.

“We have ideas, tools, and data that [are] not being exploited in the physical sciences,” Montgomery said. “There is a lot that could and should be done to bring the expertise from health and social sciences to these issues.”

The effects of climate change differ depending on where the city is located, Montgomery said. Rising sea levels and an increase in flooding and landslides from coastal storms are key threats to low-lying coastal cities. Many cities in the developing world lie not on the coast but in arid areas where water security is a problem, particularly for those relying on meltwater from mountain glaciers, which are under stress from rising global temperatures. These cities deal not only with the prospect of drought, but also with reduced electricity supplies from hydropower, reduced agricultural production, and heat stress on their populations.

“This is an area that needs some sustained research attention,” Montgomery said.

Poor people tend to live in places that are already less desirable and environmentally risky, prone to flooding and other hazards. Poor drainage and sewage processing increase the risk of flooding and also of the spread of infectious disease during flood events.

In response to questions, Montgomery said that much of the work that would make these communities better able to withstand climate challenges are things that ought to be done anyway to make the cities safer and more secure for residents. Climate change just increases the consequences if nothing is done.

“What climate change is really doing in this story is adding urgency. You’re raising the temperature on the issue,” Montgomery said. “The payoff for doing what ought to be done already … is great.”