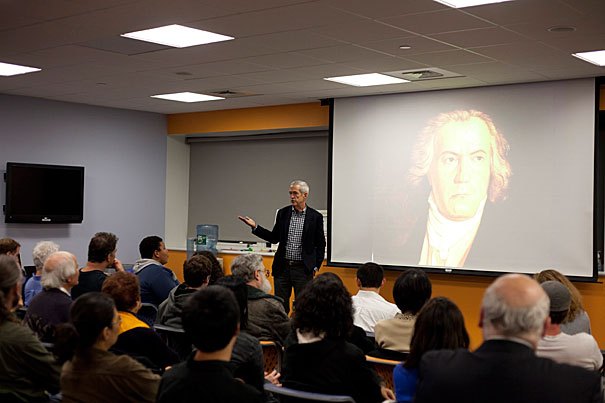

Thomas Kelly, Harvard’s Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music, addressed a crowd at the Harvard Allston Education Portal. Kelly’s talk was based on his popular course “First Nights,” where he explores the performance premieres of five seminal music works through a cultural, musical, and historical lens.

Julie Moscatel/HPAC

Overjoyed

Professor delights in details of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

Who could have guessed that Ludwig van Beethoven had so much work to do finding a place to perform his iconic Ninth Symphony?

Not only did the famously irascible composer — who was completely deaf by the time of the premiere — have to write the work, gather together an orchestra, and copy out the score for the instruments, he also had to scour 1824 Vienna to locate a suitable concert hall.

That’s just one example of the kind of intimate historical detail served up in a lecture this week (Nov. 9) by Thomas Kelly, Harvard’s Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music, who addressed a crowd at the Harvard Allston Education Portal.

Punching the air to a booming drumbeat, mouthing along to the work’s famed “Ode to Joy” choral finale, or taking on the role of conductor, directing the phantom orchestra before him, Kelly was in his element while playing snippets of the famous work.

The lively presentation was the first lecture this semester in an ongoing series that brings core General Education lectures offered to Harvard College undergraduates to the community. The talk was based on Kelly’s popular course “First Nights,” where he explores the performance premieres of five seminal music works through a cultural, musical, and historical lens.

“What better thing to share with the public than Harvard’s vision for what’s broadly important to the liberal arts,” said Robert Lue, professor of the practice of molecular and cellular biology, director of life sciences education, and the portal’s faculty director. “It’s the perfect thing to share with the community.”

Talks have included Harvard Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology Florian Engert’s lecture on “Finding Neuro: Insights from the Zebrafish on How the Brain Works,” and a discussion with Maria Tatar, John L. Loeb Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures and of Folklore and Mythology, titled “Fairy Tales and the Culture of Childhood.” On Dec. 7 at 6:30 p.m., Harvard Provost and Professor of Neurobiology Steven E. Hyman will deliver a talk based on his course “Drugs and the Brain: From Neurobiology to Ethics.”

Telling his audience that he uses “First Nights” to “help people understand how lucky they are to be alive on a planet that has art on it,” Kelly took the crowd through the piece’s four movements, explaining how Beethoven smashed the standard operating procedure of the day for symphonic works. Whereas composers like Mozart and Haydn followed a formula that began their works “loud and busy,” in part to try to get the audience’s attention, Beethoven did the opposite, starting his Ninth Symphony with what Kelly called “cosmic background sound.”

“You can’t be absolutely sure it’s started. It’s not fast, it’s not slow, it’s not in a major key, it’s not in a minor key. You don’t know anything,” he said.

Beethoven was also the first major composer to include voices in a symphonic work, noted Kelly, adding that the composer also broke with tradition by reusing themes from earlier parts of the piece in later movements.

Beethoven borrowed words for his rousing “Ode to Joy,” the dramatic chorus in the piece’s final movement, from a poem by German poet Friedrich Schiller that was crafted to sound like a fraternal drinking song.

Selecting lines like “all men should be brothers,” Beethoven conveyed a strong message about the emerging age of the Enlightenment and the “value of individual human beings,” the lines acting as a sort of critique of repressive societies and autocratic governments.

“Beethoven took a drinking song and made it into, what we might call, the world’s national anthem,” said Kelly.

The day of the performance, Beethoven, who was known for his typically unkempt appearance, was sporting a new haircut. How did Kelly know that the composer was freshly coiffed? Because he couldn’t hear, Beethoven had to rely on a conversation book, where people wrote down everything they wanted to say to him. One person, said Kelly, commented on the composer’s new hairdo in the log.

“We know everything he did all day long. … I like the idea of putting yourself really in the time.”

Local musician and North Brighton resident Tim McHale called Kelly “an incredibly vibrant professor,” and said the presentation had changed his perspective on the classical repertoire.

Noting that he doesn’t listen to classical music, McHale said, “but I will now. … He inspired me to look at it a little more deeply.”