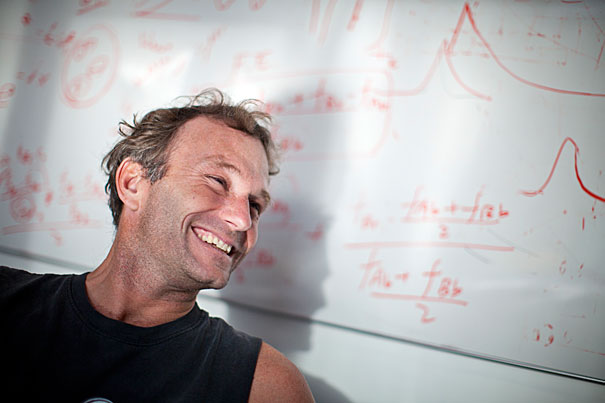

One way that Florian Engert has helped to make science fun for his students is by building a community. “I try to promote communal activities,” says the professor of molecular and cellular biology. “We rent a house for a lab retreat twice a year. We play sports.”

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

Biology researcher’s on a roll

Engert keeps moving, whether at work or play

On the second floor of Harvard’s Biological Labs, next to signs warning of biohazards and pointing to eyewash stations, there used to be another sign: No rollerblading.

The incongruous warning was apparently directed at Florian Engert, who has been known to wheel about the otherwise sedate hallways. Now that he has been tenured as a professor of molecular and cellular biology, the prohibition has quietly vanished.

Engert moves like someone accustomed to more demanding pursuits. He seems to be perpetually heading from one task to another, darting purposefully between research projects and lectures. He appears tireless and endlessly focused, yet lighthearted. The Rollerblades still sit sheepishly by the lip of his desk.

Harvard is the latest stop in a series of research institutions for the young professor. Engert was born and raised near Munich, Germany, the son of a baker and a hairdresser.

“My parents had very blue-collar professions,” he says. In post-World War II Germany, “it wasn’t about how clever you were but what jobs were available. They were intellectual but not highly educated.”

His parents instilled their intellectual curiosity in their children. As an undergraduate, Engert studied not neuroscience but physics. He also found himself drawn to adventure.

“I love the mountains and the oceans,” he says. He hiked in the Alps. He ran marathons. As an undergraduate, he took a semester off to sail across the Atlantic. “I grew up near a lake,” he offers by way of explanation.

At the end of his undergraduate study, he decided to join a neuroscience lab for his last research project. That led to graduate work in neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute.

“In physics, the choice appeared to be elementary particles or astrophysics,” he says. “But that seemed very far removed from daily life: too large or too small. Neuroscience is really what defines us as humans.”

As a graduate student, Engert embarked on another quest, this time to the Himalayas. His Ph.D. adviser asked him not to go, worried about the future of Engert’s research project, should something untoward happen at high altitude.

“One of the concerns was what would happen to the results if I should die on the mountain. But I came back and finished my degree,” Engert says.

From Munich, Engert went to the University of California, San Diego, where his adventure of choice was surfing. Then, eight years ago, he came to Cambridge, Mass.

“Not a lot of mountains, not a lot of ocean here” to tax him, he muses. “But the community here makes it easy for science to be fun.”

One way that Engert has helped to make science fun for his students is by building a community. His office in the Bio Labs is directly off the common space for his group. If you hope to find the professor by looking for his name on the door, you will find instead a room with a foosball table, a coffee machine, and perhaps a pile of muffins.

“I try to promote communal activities,” he says. “We rent a house for a lab retreat twice a year. We play sports.”

Referring to the shockingly competitive annual beach volleyball tournament at the Bio Labs, he adds: “Two years now, we have almost won the Rhino Cup. We will win.”

Engert credits the fun, communal atmosphere for the productivity of his group. He gives his students freedom to be creative. The result is a group of self-motivated young neuroscientists who consistently turn out fresh work and new methods.

Staring out his second-floor window in a rare static moment, Engert says simply, “This is the most collaborative scientific community I have been part of. I really like it here.”