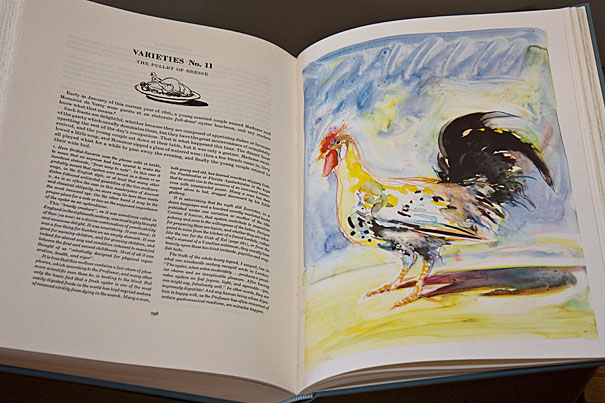

In a first-floor conference room at the Schlesinger, a temporary exhibit called “A Taste of History,” features a selection of cookbooks from the library’s famous collection. The exhibit is just one part of a two-day conference titled “Why Books?”.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Why Books?’

Harvard is field of battle for print’s fate in a digital age

Why books?

In a two-day conference of the same name, experts from Harvard and elsewhere are investigating the fate of print in a digital age. The field of battle, Thursday and today (Oct. 28-29), is the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, the home of a prestigious fellowship program and one of Harvard’s most durable crossroads for interdisciplinary discourse.

After a decade of debate, the consensus is that books are not going away — and that at best electronic communication will align powerfully with the tradition of ink and paper.

“Why Books?,” two years in the making, was organized by a faculty committee headed by Leah Price ’91, RI ’07, and Ann Blair ’84, BI ’99. Price is a professor of English, Harvard College Professor, and the Radcliffe Institute’s senior adviser in the humanities. Blair, also a Harvard College Professor, is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History.

Today’s (Oct. 29) conference at the Radcliffe Gymnasium consists of a series of four panels — on future text formats; storage and retrieval; circulation and transmission; and reception and use. There is a conference hashtag for Twitter: #whybooks.

“Why Books?” started Thursday (Oct. 28), logically, with explorations of both digital and print resources at Harvard. Conference attendees took in 13 workshops — visits to University facilities that make, store, conserve, distribute, and (yes) digitize books and other printed matter.

At the Radcliffe Gymnasium, Marilyn Dunn, executive director of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, demonstrated Harvard’s Web Archive Collection Service (WAX), a mechanism for harvesting and preserving Web content.

At Harvard Law School, experts from the Special Collections staff made one presentation on 16th century law books and another on books that illuminated the pedagogy of Christopher Columbus Langdell (1826-1906), the Law School’s first dean and a pioneer in case-method teaching.

At Harvard University Press, Art Director Timothy Jones outlined the challenges of book and editorial design as the world moves into a digital environment.

At Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center, those on tour observed conservators at work and learned about the art and science of preserving fragile books, maps, drawings, and other printed materials. (Some are so delicate they can’t be exposed to direct light.)

At Bow and Arrow Press, visitors went back to the future, getting a hands-on history of a vintage letterpress operation from Zachary Sifuentes ’99, resident tutor in poetry and arts at Adams House.

There were other workshops on e-books, preserving digital materials, printing before the industrial age, and how original manuscripts illuminate an artist’s creative methods and even the business environment they operated in. (That was at the Houghton Library, where visitors looked at written pages from William James, Samuel Johnson, and Emily Dickinson.)

In a first-floor conference room at the Schlesinger, visitors roamed through a temporary exhibit called “A Taste of History,” a selection of cookbooks from the library’s famous collection.

There was a 1679 edition of a cookbook by German author Anna Wecker, the world’s first female food writer. Its title in English reads “New, delightful, and useful cookbook,” and it was first published in 1596. In the back is an appendix on Parisian cooking — an early sign of the dominant French cuisine that would soon sweep Europe.

Also on display was “What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking” (1881), the first cookbook by a freed slave; a 1943 wartime version of Irma S. Rombauer’s “The Joy of Cooking,” including what she called “emergency chapters” on meatless and sugar-free dishes; Julia Child’s copy of M.F.K. Fisher’s “How to Cook a Wolf”; and a tiny cookbook printed in 1601 in Venice, Italy, the Schlesinger’s oldest cookbook volume.

“These are my babies,” said Barbara Wheaton, whose 1982 “Savoring the Past” legitimized culinary arts as a window onto history. The longtime Harvard food scholar, now honorary curator of the Schlesinger’s Culinary Collection, delivered a loving précis of a few of the volumes.

Summing up the books with her was Marylène Altieri, the Schlesinger’s curator of Books and Printed Materials.

“That any of the tradition gets written down is miraculous,” said Wheaton of books about cooking — volumes that often capture the voices of women and male artisans who otherwise would be lost to history. These were “people who didn’t expect that what they said would matter,” she said.

Any conference on the fate of books would do worse than to start with books about cooking, said Wheaton.

“One of the first things our ancestors did … was to talk about food” — a topic so vital to survival that it helped shaped language millennia before print arrived, she said. “To talk about getting it, to talk about preparing it, to talk about the sensations of eating it — with all the moral and sensual and practical questions that arise from getting enough stuff … to keep the organism going.”

As for broader question of the fate of print that will come up in today’s “Why Books?” conference — “I think about it every day,” said Wheaton.

“I’m absolutely nuts about computers and the Internet. I’m building a database that is better than having an expensive car because I can do such wonderful things with it,” she said. “But nothing replaces books. Ever.”

Wheaton reached in front of her and touched the edges of Abby Buchanan Longstreet’s “Dinners, Ceremonious and Unceremonious,” an 1890 volume on table etiquette.

“The thing itself,” she said of the volume. “This book is small and dainty and civilized. It has gold letters and a nice tasteful green (cover).”

By holding it, and reading it, said Wheaton, “you’re going to have a decorous experience.”

As her visitors filed out, she added: “Come back and read a book. Read 10.”