Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stepping into action

Harvard programs help incoming freshmen to get into the flow

This was New England’s summer of endless sunshine — that is until a group of incoming Harvard freshmen started hiking through New Hampshire’s woods. Then a nor’easter swept in and stalled, dumping four days of rain on the campers, most of them still half-strangers to each other.

Suddenly, it was the season of soggy bonding.

Last week’s rain and mist draped an unexpected chill across the top of Lovewell Mountain, arriving just as the hikers finished their well-earned lunch. But instead of groans, shivers, or even silent stoicism, the participants in Harvard’s First-Year Outdoor Program (FOP) dug through their heavy backpacks, added a layer of clothes, and topped it with rain gear. Then they formed a circle.

“One! Two! Let’s Play Zoo!” chanted Emma Franklin, a junior neurobiology concentrator and one of the trip’s two leaders. Franklin’s words kicked off an energetic, pantomimed game in which players made quick hand gestures representing animals. Their gestures, made to a steady, clapped beat, spread rapidly around the circle until someone missed and was forced out.

The contest continued for the next 20 minutes until a winner was declared. Then, their spirits lifted, the students hoisted their heavy loads and headed into the dripping forest toward a distant spot that would become their home for the night.

The nine students and two leaders were among more than 800 participants in Harvard’s pre-orientation programs, a quintet of activities that brought the freshmen to campus before the official College orientation began at the end of August.

The students have myriad options in getting to know their peers. Participants may head for the woods, or fan out into Boston’s neighborhoods for community service, or stay on campus to tap their artistic muses. Others help Harvard’s maintenance crews, spending the week earning extra money and prepping the dorms for the new semester. The final group, international students, has more orienting to do than the typical domestic student group, so they spend more time learning about life in America and at Harvard.

The programs, each of which contains a strong element of student leadership, expose students to fresh goals and challenges, whether hiking up ridges or learning about arts. But the main benefit of these programs, organizers say, is not a particular goal or achievement, but rather the creation of a community on which students can rely during their transition.

“We think this is a great way to start college,” said Katie Steele, Harvard College’s director of freshman programs. “You’re going to meet people who share similar interests, you’re going to know some upperclassmen, and you’re going to do something you’ve never done before.”

The pre-orientation programs are just the start. College officials labor to shrink Harvard to a manageable size for incoming students. Those efforts are more overt early when students are part of pre-orientation and orientation programs, and gradually become part of the fabric of campus life, when “freshman dorm entryways” function as mini-communities overseen by proctors, who check in on students if they’re having trouble.

Such efforts continue through the students’ first year and beyond, as undergrads find their own way into studies, activities, and groups that interest them, all with their own communities. At the start of their sophomore years, the students move into Harvard’s upper-class Houses, which are communities within a community, headed by faculty masters and including scholars linked to House life as fellows. The result is a gradual formation of a concrete sense of belonging that, for many undergraduates, continues to define their College years even when they look back decades later.

“This place works best when people feel connected,” Dean of Freshmen Thomas Dingman said. “This can be a big, intimidating place.”

The first step in the process begins even before pre-orientation. Resident deans exhaustively review incoming applications from freshmen, matching students by hand in an effort to successfully create the smallest community on campus: that of students sharing a room.

The effort, Dingman said, strikes a balance between what a student finds comfortable and steadying and what may foster personal growth, by matching likes and habits with the broadening experience that exposure to new people can bring.

“If someone always gets up early, and staying in shape is important to them, if religion is important, we can match them with someone who shares those interests but who is perhaps from another part of the country, or from another racial or ethnic group,” Dingman said.

Pre-orientation programs help students to develop a sense of community even before they meet their roommates. Annenberg Hall, Harvard’s vast freshman dining commons, is often mentioned as a tough introductory hurdle for a new student, tray in hand, scanning the rows of tables for a friendly face.

“It’ll be nice to avoid the ‘high school horror story moment’ of going into the cafeteria and not knowing who to sit with,” said Keerthi Reddy, an incoming freshman from San Diego who participated in a FOP trip. “There’s nothing like spending a week in the woods to get to know someone.”

While the official orientation programs are mandatory, the pre-orientation programs are not. Steele said some incoming freshmen instead choose to use the final weeks before coming to Cambridge working, vacationing with family, or participating in sports.

Pre-orientation programs are known by handy acronyms modeled after FOP, which was the first at Harvard, starting in 1979. The Freshman Arts Program is FAP, the First-Year Urban Program is FUP, and the Freshman International Program is FIP. (The exception is fall cleanup, run by the Dorm Crew, where students earn money by cleaning dormitories.)

When FOP began in 1979, Amy Justice was a Harvard sophomore coming off a tough freshman year. Justice, who is now a professor of medicine at Yale University, at first struggled with her pre-med classes but found her groove after signing up to be among FOP’s first student leaders. She said that weeks in the woods gave her confidence that she could handle challenges she had never faced before, and gave her a supportive community on which to rely.

“It’s an experience that stays with you for the rest of your life. It’s a source of strength,” Justice said. “I walked into Harvard and nearly flunked out. I remember thinking, ‘This is a whole different world, and I don’t understand this world.’

“The program … is not about academics. You stretch physically and [are] part of a team. It’s about being aware of other members of the team, and getting over the little things. It’s about being out in nature, where you can’t control what’s happening,” Justice said. “It’s not about who gets ahead; it’s about how the group moves forward.”

The community-building aspects of the outdoor program are replicated in other freshman pre-orientation programs, though they unite around work, the arts, community service, or understanding the United States after arriving from abroad.

Jack Cen, a senior and a captain for the fall cleanup, participated in the program as a freshman as a way to get on campus early and meet people. That worked well enough that he stayed through subsequent years because of the connections he made.

“It was nice to settle in first. It eased the process,” Cen said. “It’s a … unique set of people willing to clean bathrooms every week, week in and week out,” through the summer.

Robert Wolfreys, crew supervisor for Facilities Maintenance Operations, which runs the fall cleanup, said the students work hard, but there are orientation-style programs mixed in with the tasks. Upperclassmen take participants on tours of the Yard and Harvard Square. Activities include a massive tug-of-war and a cookout.

Fall cleanup is among the most popular pre-orientation programs, rivaling the Outdoor Program’s 300-plus, with about 350 freshmen participating, Wolfreys said. Students find themselves taking out trash, sweeping and washing floors, cleaning walls, replacing recycling bins and window screens, and checking lamps, data jacks, phones, and other dorm room equipment to make sure they work.

Students interested in the arts not only challenge themselves and meet students with similar interests, they also create an offering for the broader community, in the form of a pageant presented during orientation.

Dana Knox, program director for the Freshman Arts Program, said participants take a series of master classes with visiting artists and are encouraged to step beyond their comfort zones in their pageant work.

“We encourage students to take on fields outside their areas of expertise … to stretch and see if there is an untapped interest. We have dancers write the show and actors work on choreography,” Knox said. “The point is to find creative ways to get students into the environment of Harvard, giving them a chance to do something of specific interest to them — before the weight of classes and obligations of an academic year.”

A pageant of ideas Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Helping hands

Ty Walker ’14 helps with design, painting an “H” for Harvard and, of course, his new home.

Groove things

Meisha Brooks ’14 (from left), Tony Oblen ’14, Aviva Hakanoglu ’14 of New York, and Michael Wu ’14 harmonize and help plan the pageant’s music.

This is the remix!

Alastair Su ’14, of the musical composition team, lays down some tracks.

We built this city

Ginny Fahs ’14 (left) and Megan McDonnell ’14 paint some Harvard against the Boston skyline.

Actin’ up

Script writers Riana Balahadia ’14 (from left), Xiaoxiao Wu ’14, and Georgia Shelton ’14 bounce around ideas.

Back on the chain gang

It’s rough work for Ty Walker ’14 (from left), Sam Rashba ’14, and Matt DaSilva ’12, but the show must go on!

Dirty deeds

Brooke Griffin ’14 (from left), Diana Miao ’14, and Ginny Fahs ’14 ditch their shoes and get down to work.

It’s a freshman affair

Students from the art and design group powwow with other students and discuss the details of the show.

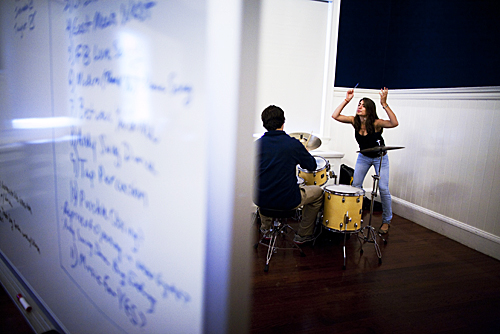

Beat it

Behind the dry erase board, Aviva Hakanoglu ’14 (right) of New York conjures magic in a drum rehearsal for the pageant.

Welcome notes

These freshmen — Alastair Su ’14 (from left), Michael Wu ’14, and Liv Redpath ’14 — hammer out the finishing touches for the pageant’s score.

Dancing queens

Pre-orientation programs, like the Freshman Arts Program, help students meet other students with similar interests and foster a sense of community. Here, Charlotte Chang ’14, Georgia Shelton ’14, Riana Balahadia ’14, and Xiaoxiao Wu ’14 rehearse for the big event.

Paint it blue

The New College Theatre stage gets a fresh shining, as incoming freshmen in the Freshman Arts Program rehearse and prepare for their annual pageant.