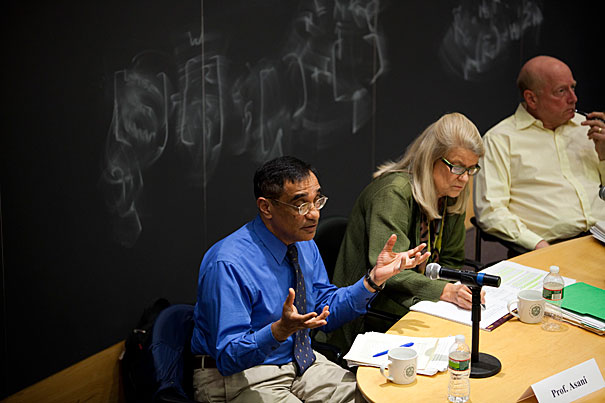

“There are certain groups that are unable to come to terms with the reality that 21st century America is culturally, religiously, and ethnically the most diverse country in the world,” said Harvard Professor Ali Asani. “Groups that are threatened by this diversity have consistently portrayed Muslims as ‘the other.’ ” Asani (left) was one of three panelists at the teach-in. Also on the panel were Diana Eck (center), professor of comparative religion and Indian studies at Harvard Divinity School, and Mark Tushnet, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Harvard Law School.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A backdrop on Islam in America

Teach-in offers historical perspective on mosque controversy

American leaders who criticize the proposed Islamic community center in lower Manhattan are not only shamelessly exploiting American fears about Islam for political gain, but are fruitlessly flailing against a new demographic reality, said Ali Asani, professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures at Harvard.

Asani was among the participants at a packed teach-in on Tuesday (Sept. 21) in Boylston Hall that explored why the proposed center has become such a national controversy.

“There are certain groups that are unable to come to terms with the reality that 21st century America is culturally, religiously, and ethnically the most diverse country in the world,” Asani said. “Groups that are threatened by this diversity have consistently portrayed Muslims as ‘the other.’ ”

Sponsored by a tapestry of organizations — including the Pluralism Project, the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, and the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program —the teach-in tried to put the mosque controversy into historical context.

Characterizing a particular religion or ethnic group as a threatening “other” is not new to American history, participants said. There have been similar movements against Catholics, Jews, Mormons, Chinese, and immigrants at various points in American life, noted Diana Eck, professor of comparative religion and Indian studies at Harvard Divinity School. As the Muslim-American community grows and its mosques become more visible, the nation’s Muslims, likewise, have encountered similar “anti” forces, she said.

Opposition to American mosques also pre-dates the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Eck said the Pluralism Project has recorded incidents of arson and vandalism against mosques since 1991.

But what was once expressed as veiled concerns about noise, traffic, or zoning is now being “overtly expressed” as outright opposition to Islam, she said. Various groups are now reaping publicity by attacking the idea of building near Ground Zero, while organizations supporting the Islamic center project have been ignored by the media, Eck said.

“One has to really ask the question: How is it that the media responds so quickly to those who want to see this as placing a ‘victory mosque’ on top of ruins of Ground Zero?” Eck asked.

Moreover, Asani said, the media’s reliance on “angry, bearded old men and hijabi women” as representative of “authentic” Islam presents a distorted viewpoint. “In the attempt to represent the Muslim as ‘the other,’ you don’t see any reference to [how] the Muslim presence in the United States actually pre-dates the creation of the United States,” he said. “There is a whole history that has been totally ignored or denied.”

From a legal standpoint, there is little doubt that proponents of the Islamic center have a right to build the facility, said Mark Tushnet, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, even if something he dubbed the “heckler’s veto” might be employed. That is, proponents have a right to build the facility but opponents may be entitled to fight the location as inappropriate.

Why are anti-Islamic sentiments being voiced now, nearly a decade after the Sept. 11 attacks? “I frankly think this is due to American politics and the upcoming midterm election and the attempt by certain political groups to take control of Congress,” Asani said. The language of some U.S. politicians often parallels “word for word” the anti-Muslim rhetoric of fundamentalist politicians in India, he said.

During a question-and-answer period, Fariba Parsa, a visiting postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, wondered whether educating Americans about Islam would have any real effect.

Asani said that religious “illiteracy” was a global problem, not just in the United States, and that there is widespread ignorance about Western culture and religion in Muslim societies.

What is most ominous is “not the clash of civilizations, but the clash of ignorance,” he said.