In a continuing celebration of William James, Harvard’s Houghton Library houses the exhibit ” ‘Life is in the transitions’: William James, 1842-1910.” The exhibit, which includes sketches, manuscripts, lecture notes, and letters, will continue through Dec. 23. In this 1865 photograph, William James (front row, far left) is among members of the Thayer Expedition.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A life of transition

Exhibit tracks how William James evolved as philosopher, scholar

The notion that a life’s worth is measured more by the path it has taken than by its final destination is at the heart of a new exhibition at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

“ ‘Life is in the transitions’: William James, 1842-1910” is a diverse collection of manuscripts, photos, letters, sketches, and correspondence that carefully chronicles the turning points in the life of the groundbreaking scholar, author, and philosopher considered by many the father of American psychology.

“Life is in the transitions as much as in the terms connected; often, indeed, it seems to be there more emphatically, as if our spurts and sallies forward were the real firing-line of the battle, were like the thin line of flame advancing across the dry autumnal field which the farmer proceeds to burn,” James wrote in 1904’s “A World of Pure Experience.”

The eight display cases in the exhibition reveal a complex, brilliant, lovable, fallible character searching for answers to life’s most pressing questions. They also show a man continually striving to be understood, to bring a bright clarity of thought and meaning to his ideas and work, and to find his place in the world.

The show explores James’ eclectic mix of interests and intellectual pursuits: his early passion for art; his excursion to Brazil with the famed naturalist Louis Agassiz; his time at Harvard as a medical student and teacher; his interest in the metaphysical; his exploration of religion; and his great philosophical writings.

“There is nothing so complete, so generous,” said curator Linda Simon, a professor of English at Skidmore College, of Harvard’s vast James holdings, the majority of which were donated to the University by James’ wife in 1923. Simon has also written a biography of James, “Genuine Reality.”

Culling through the works, Simon chose to highlight the crossroads in James’ life that reveal how his changing interests, attitudes, emotions, and opportunities molded his personality and shaped his professional career and intellectual pursuits.

“In each case there is a feeling of ‘what if,’ ” said Simon. “There are so many points in his life where he could have said ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ or ‘this way’ or ‘that way.’ That is one of the things I wanted to point out, that it wasn’t a life that necessarily had to be lived the way that it was lived.”

The first case reveals James’ desire to become an artist, much to the dismay of his father, who frowned on the prospect. In a letter written to his parents around 1860, James pleads with them to explain “the reasons why I should not be an artist.” The same display includes a series of sketches by the talented James. In one of his most famous drawings, which shadows his own struggles with depression, a man sits in a chair with his head bowed under the words “Here I And Sorrow Sit.”

In another case, James’ diary offers up some of the scholar’s deepest feelings about his depression. A close inspection of the book reveals that some pages have been carefully cut out, perhaps by the family, in an effort to shield the most intimate side of the scholar from curious eyes.

The exhibit includes information on James’ 34-year teaching career at Harvard, which encompassed subjects as diverse as anatomy and physiology, natural history, psychology and philosophy.

Letters in the exhibition shed light on his family ties, his struggles to declare his love for his eventual wife Alice, his close connection to his brother Henry, and the loving but often professionally critical nature of their relationship.

Early versions of his essays “Pragmatism” and “The Moral Equivalent of War” are also on view. The reworked manuscripts, replete with lines deleted, copious notes, and inserted words, offer important insights into “the way James’ mind was working,” said Simon.

“He was always questioning and looking for the new. He was never completely satisfied, and that’s what makes him a very appealing figure, because I think most people do the same,” said Leslie Morris, curator of modern books and manuscripts at Houghton, who helped to organize the exhibition.

“It’s a little reassuring to know that someone of the stature of William James … went through all of this too.”

The exhibition opening matched the last day of a symposium, “In the Footsteps of William James,” organized by the William James Society in collaboration with the Chocorua Community Association and the Houghton Library to honor the centennial of his death.

Included in the discussions was an informal talk by James Kloppenberg, Harvard’s Charles Warren Professor of American History, titled “What Makes William James Significant.”

Kloppenberg, who has taught James’ work for the past three decades, said that when he asks his students to name the writings that have had the biggest impact on them, “the name that comes up more often than any other is William James.”

And while his students are inevitably drawn to James’ struggle to find meaning in his own life, and his lively personality (one, in the words of his sister Alice, “so vibrant it was as if he was born fresh every day”), it’s his work, said Kloppenberg, that resonates the most.

Through his work, students explore questions of what constitutes the complete understanding of human experience; the significance of religion and religious experience; why people are willing to die for an idea; and the notion that “there is something special in every individual.”

In James’ writings, said Kloppenberg, they find ideas that are “fascinating and worth their time.”

The show is on display through Dec. 23.

As a companion to the show, Simon and Morris compiled a collection of essays — titled “William James in His Times and Ours” — from a wide range of scholars commenting on various aspects of the exhibition. Contributors include Harvard’s Louis Menand, Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of English; Harvard University President Drew Faust; author Gore Vidal; Steven Pinker, Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology and Harvard College Professor; David C. Lamberth, professor of philosophy and theology at Harvard Divinity School; and Princeton Professor Cornel West.

William James, 1842-1910 Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

James brothers

Author Henry James with his brother William at Lamb House in September 1900. The family photo is among the collection of manuscripts, photographs, letters, and sketches on view at Houghton Library.

James scholar

Linda Simon, professor of English at Skidmore College, is curator of the William James exhibit. Simon, a William James expert, is the author of “Genuine Reality: A Life of William James” and a collection of essays on William James titled “William James Remembered.”

Change of course

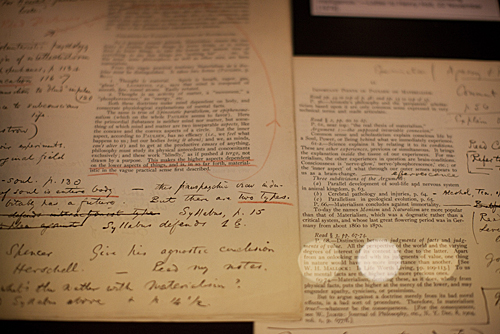

William James’ annotations and revisions from his syllabus.

Studio shot

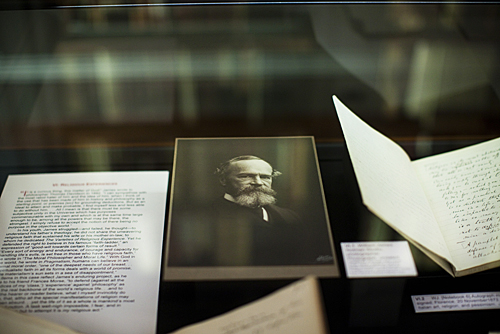

A photograph of William James by Notman Studio is among the manuscripts and books on display at Houghton Library.

Through the looking glass

Frances Davidson (left) and her daughter Jean Davidson enjoy the exhibition.

Positively William James

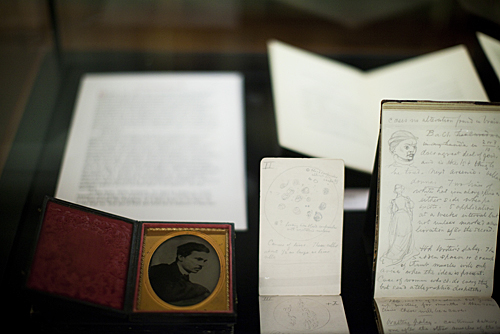

One of the cases on display shows an ambrotype of William James. An ambrotype is an early kind of photograph consisting of a glass negative backed by a dark surface so as to appear positive.