Susan Mango: “Art and biology just aren’t that different. I realized sometime in graduate school that I think about biology differently from some scientists. For me it’s very grounded in visual and spatial representation.”

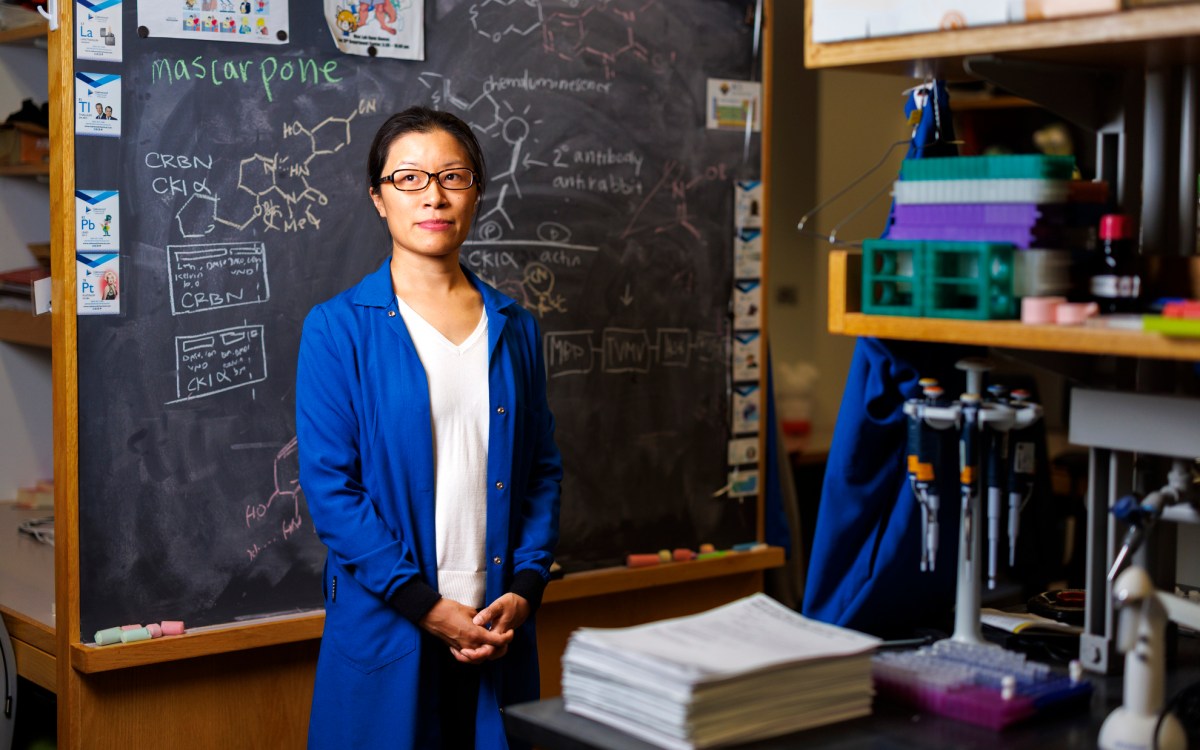

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The art of science

Unorthodox approaches help to fuel Susan Mango’s research

After earning a biochemistry degree from Harvard College in 1983, Susan Mango was on the path to becoming a scientist. She loved thinking about puzzles, the beauty of scientific questions, and the elegance of experimental design. Graduate school in biological science was the clear next step.

Then Mango spent a postgraduate year doing something completely different: She took a job at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., working on conservation of artworks.

“Taking that time, not having set a rigid trajectory from undergraduate science student to full professor, was liberating,” Mango said. “I think it helped keep science fun.”

Mango, who rejoined Harvard this academic year as professor of molecular and cellular biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, says her interest in art naturally complements her interest in science.

“Art and biology just aren’t that different,” she said. “I realized sometime in graduate school that I think about biology differently from some scientists. For me it’s very grounded in visual and spatial representation.”

“Biology is all about puzzles and imagining processes,” she added. “I like puzzles. They’re fun.”

Mango’s unorthodox approach to experimental research has led to the kind of creative, elegant studies that push the limits of biology. Her work on pharynx (a cavity area behind the mouth) development in nematode worms has provided biologists with one of their most robust models of organ formation.

In 2008 her ingenuity was rewarded when the MacArthur Foundation phoned out of the blue to award her one of its “genius grants,” which carries with it $500,000 in no-strings-attached funding. Mango said that call — notable for the MacArthur representative’s dogged insistence that he really was who he said he was, and not some prankster — triggered an enjoyable, days-long process of reconnecting with long-lost friends, colleagues, and mentors who read of her honor.

Mango grew up in New York, London, and Washington, the daughter of a peripatetic professor of Byzantine history. She in effect “rebelled” against her humanist parents by cultivating an interest in science. Her own career has taken her all over the country. From Harvard, she went to Princeton to complete graduate work, moved on to a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Wisconsin, and eventually landed on the faculty of the University of Utah’s School of Medicine and Huntsman Cancer Institute.

While in Utah, Mango developed a reputation for forward-thinking research. High-impact journals have regularly published her groundbreaking work on organogenesis. Mango’s approach to puzzling out questions in biology not only lets her think about old questions in new ways, but also allows her to find new questions in old subjects.

After decades in the lab, biological experimentation continues to intrigue her, she said, because “you think the answer is going to be black or white, but it’s always some shade of gray.”

Now, her Harvard appointment brings Mango full circle, into an office next door to her freshman biology professor, Richard Losick, the Maria Moors Cabot Professor of Biology.

“It’s good to be back,” she said. “This is the next step. It’s an adventure.”