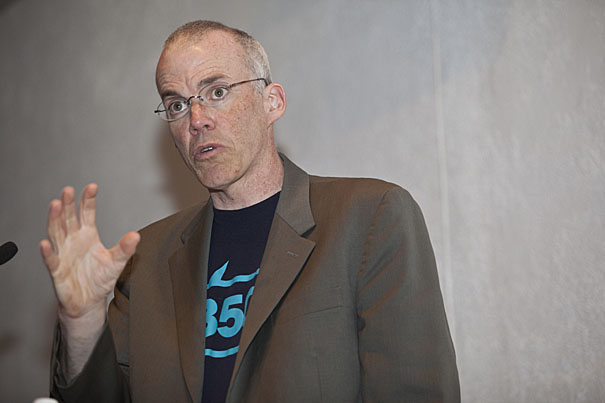

Current U.S. farming and food systems are like much of modern Western life, intensively dependent on oil. Farming requires fertilizers, tractors, and carbon-based transportation systems, author-turned-activist Bill McKibben ’82 told his audience at Harvard Divinity School. “The food you eat is essentially marinated in fossil fuel before it reaches your lips.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Reality check

Environmentalist Bill McKibben reimagines life on a fragile planet

Last year, author-turned-activist Bill McKibben ’82 spent just 60 days sleeping in his own bed. The rest of the time he was on the road, organizing what he deems essential to force political change on a warming planet: a global grassroots movement.

In remarks at Harvard on Monday (March 8), McKibben — whose 1989 book “The End of Nature” popularized the science of global warming — apologized for the greenhouse gases that his worldwide travel consumed, a bigger carbon footprint than most small villages, he said. But with glaciers melting, oceans acidifying, and climate zones shifting, he said, the world needs a political makeover fast.

His new organization, 350.org, could help by educating the political classes to a new reality that greenhouse gases shrouding Earth should go no higher than 350 parts per million in carbon dioxide equivalents.

One problem, of course, is that the level of such gases is already at 390 ppm “and rising fast,” McKibben told listeners in a crowded Sperry Room at Harvard Divinity School. The world is running out of oil, though perhaps slowly, he said, and that requires the political will to think beyond petroleum.

Beyond oil’s decline are the stark, immovable facts of physics and chemistry, said McKibben, the “deep physical limits” caused by proliferating greenhouse gases.

So what can people do?

“A new logic prevails,” he said in a talk called “Reality Check: How the Facts of Life on a Tough New Planet Shape Our Choices.” The event was part of a lecture series called “Ecologies of Human Flourishing,” co-sponsored by the Center for the Study of World Religions. The session included a conversation with Harvard climate scientist Daniel Schrag.

By this “new logic,” said McKibben, security and stability will become more important that constant economic growth. “All the glory associated with the concept of growth will start to tarnish,” he said. “Maturity will become our credo.”

He said that centralized energy systems dominated by fossil fuels will be slowly replaced by systems that are dispersed and localized, and that rely on renewable energy. McKibben’s house in the Vermont woods, for instance, has an array of solar panels on the roof. “On sunny days,” he said, “I’m a utility.”

And food systems — the way we grow and distribute what we eat — will shrink from global to regional models, he predicted. Farmers’ markets are among the fastest growing sectors of the economy. (In Madison, Wis., one regional market draws 100,000 shoppers on a Saturday.) And the last five-year census of U.S. agriculture showed the first growth in the number of farms in 125 years, most of them small-scale operations.

Current U.S. farming and food systems are like much of modern Western life, intensively dependent on oil. Farming requires fertilizers, tractors, and carbon-based transportation systems, he said. “The food you eat is essentially marinated in fossil fuel before it reaches your lips.”

In addition to asking what we can do, said McKibben, another important question is: How can we flourish? Perhaps by living better, but with less, he said.

He sketched in a world of sprawl, increasing social isolation, and declining happiness, an America of “enormous houses, and enormous cars to drive between them.”

McKibben said the chief untold consequence of our dependence on fossil fuels is that oil “has made us lonelier people than we were before.” We are inhabitants of “bigger houses farther apart from one another,” he said, isolated by television, and enjoying half the meals we had with friends in 1950. Meanwhile, “human satisfaction” polls show that American happiness peaked nearly 60 years ago, despite a trebling of material prosperity since then.

“These are enormous changes,” said McKibben, but shifting our sense of scale might help. He cited a recent study showing that shopping in farmers’ markets engendered 10 times the number of personal interactions that a stroll under fluorescent lights at the supermarket does.

“I love hearing Bill talk. Bill always makes me hopeful,” said Schrag, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and professor of environmental science and engineering, and director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment.

But other reality checks are required, he said. For instance, only about 40 percent of Americans think climate change is actually happening. And just 15 percent think climate change is “actually serious,” said Schrag.

Add to that the speed and gravity of the ecological consequences of climate change. California’s rivers that are now fed by glacial melt may run dry by the end of the century, stranding water-hungry farms. And by as early as 2035, melting glaciers in the Himalayan mountains may cause dry conditions on farms far downriver that presently feed 3 billion people.

Then there are problems with renewable sources of energy, said Schrag. Rooftop photovoltaic solar arrays such as McKibben’s are expensive.

Renewable resources such as wind and solar will require massive construction projects, an idea offensive to many people in an environmental movement inspired by pastoral ideals.

Then there is the issue of energy density, said Schrag. A wind farm may create a watt for every square meter of its physical footprint. But a coal mine in Wyoming may represent an energy potential that is a million times denser.

A social movement such as McKibben’s 350.org is important, and even necessary, said Schrag. But any such movement “has to support trade-offs,” like the “massive building projects” that a shift to renewables will require.

McKibben said he understands that, and he is in favor of a wind farm proposed near his beloved Siamese Ponds Wilderness in New York’s Adirondack Park. “Build this as fast as you can,” he said, bowing to the grave urgency of global warming. “There’s not going to be winter there in 40 years.”

But at the same time people make compromises in the cause of renewable energy, they can certainly do more with less, said McKibben. Profligate use of energy is “astonishing,” he said. “We’ve spent the last decade driving semi-military vehicles back and forth to the grocery store.”

This year’s campaign by 350.org includes a “great power race,” he said, a competitive challenge to universities in China, India, and the United States to prompt novel ideas for sustainable energy.

Last year, 350.org sponsored the largest political demonstration held worldwide, with 5,200 rallies in 181 countries, which engendered 25,000 pictures on the group’s Web site.

The capstone day this year for 350.org is Oct. 10 — 10/10/10 — with a “global work party” that will install solar panels, lay out bike paths, dig community gardens, and demonstrate other local projects that have a light carbon footprint.

Global warming is too grave a problem to solve one project at a time, but a worldwide gesture, said McKibben, “will help us make the point to our leaders that if we can do this work, they sure as hell can too.”

Upcoming

Next in the “Ecologies of Human Flourishing” series: “Does Thoreau Have a Future? Reimagining Voluntary Simplicity for the Twenty-First Century,” a lecture by Lawrence Buell, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature in Harvard’s Department of English. It will be held Thursday (March 25) from 5:15 to 7 p.m. in the Sperry Room, Andover Hall, 45 Francis Ave., Cambridge, Mass.