University namesake celebrates 400th

It is 1607 in England.

Queen Elizabeth I has died only four years earlier. King James I, her successor, has already commissioned a new Bible translation that will indelibly mark the English language four years later.

Alive and well and working in London, William Shakespeare has recently completed “King Lear,” “Macbeth,” and “Antony and Cleopatra.” William Byrd publishes his second volume of “Gradualia,” a major compendium of church music.

In continental Europe, Monteverdi premieres his landmark opera “Orfeo.” Painters like Caravaggio, El Greco, Hals, and Rubens are active. Artemisia Gentileschi is a girl of 14; Diego Velázquez, a lad of 8; Rembrandt van Rijn, only 1. Cervantes enjoys the continuing success of “Don Quixote” (Part I, 1605). Astronomers like Galileo and Kepler will soon reshape our vision of the solar system.

Across the Atlantic, English colonists finally gain a lasting foothold in the Americas with the founding of Jamestown.

Into this world of expanding horizons, John Harvard was born to Robert Harvard, a Southwark butcher and local official, and his second wife, Katherine Rogers Harvard.

Because the births of common folk were not regularly recorded at this time, baptismal registers are often the first documents attesting to new arrivals in the Christian community. In an age of high infant mortality, many parents had their children baptized within days of birth, lest they die outside the church’s circle of blessing.

And so, on Nov. 29 (by the calendar then used in England), Robert and Katherine took their second son to be baptized in the Chapel of St. John the Evangelist at St. Saviour’s Church (attended by Shakespeare himself, and now London’s Southwark Cathedral. The baptismal site was renamed “Harvard Chapel” in 1905).

Nothing of note developed in John Harvard’s life until 1625, when his father and several siblings died of the plague. Cousin Thomas Harvard bought the butcher business, while mother Katherine soon married and lost two other husbands.

In December 1627, John Harvard entered Cambridge University’s Emmanuel College, established in 1584 for Protestant ministerial training. When Harvard turned 21, he received £300 from his father’s estate. By 1637, after the deaths of his mother and cousin, most of the family fortune (some £2,000) had passed into his hands.

Harvard completed his bachelor’s degree in 1632 and his master’s degree in 1635. Emmanuel records reveal little beyond his signature. In April 1636, he married Ann Sadler (sister of his friend John Sadler, future master of Cambridge’s Magdalene College). Just over a year later, the couple set off for Massachusetts Bay Colony. In August 1637, they received land on Gravel Lane (in Town Hill, now City Square) in Charlestown, then a settlement of some 150 dwellings.

The young clergyman had barely put down roots before consumption struck him dead in September 1638, not long after the nameless “colledge” so generously remembered in his will had begun teaching its first students. Harvard’s remains were buried in Charlestown, but the grave marker disappeared during the Revolutionary War. In 1828, alumni raised funds for the granite-obelisk cenotaph still standing in Charlestown’s Old Burying Ground.

At the October 1884 unveiling of Daniel Chester French’s now-familiar bronze of a hypothetical John Harvard (no authentic likeness exists), Harvard President Charles William Eliot stood on the Delta (the triangular patch west of Memorial Hall where the sculpture sat until 1924) and shared the meaning he had mined from John’s distant, enigmatic life: “He will teach that one disinterested deed of hope and faith may crown a brief and broken life with deathless fame.”

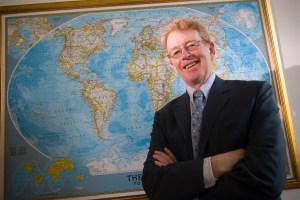

On Nov. 25, the Rev. Professor Peter J. Gomes, the Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church and Plummer Professor of Christian Morals, delivered a sermon at Southwark Cathedral in honor of the 400th anniversary of John Harvard’s birth and baptism. For full text of his sermon, visithttp://www.southwark.anglican.org/cathedral/sermons/pg20071125.htm.