Casts of monuments preserve fading treasures

Harvard collection turns historical afterthoughts into valued resource

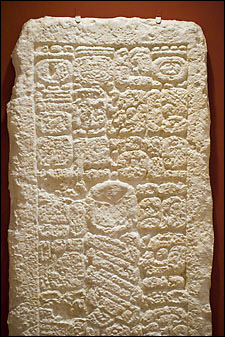

The carved stone monolith tells the story of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, the 16th and last ruler of the Maya city of Copan, one of the most important sites in Maya history.

Created by stone carvers more than 1,200 years ago, the monument’s 20 glyphs tell of Yopaat’s inauguration, of his conjuring an ancestral spirit 20 years into his reign, and of his heritage as the son of a royal woman from Palenque in what is now Chiapas, Mexico.

Peabody Museumn, 11 Divinity Ave. Open daily 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The exhibit features some of the most important and valuable casts from the unique Mesoamerican collection.

But the monolith – or “stele” – was lost even before experts knew how to decipher the glyphs of written Mayan.

The original, after the Maya habit of re-using old stoneworks, was broken up by nearby villagers and incorporated into the stone wall bounding a local cemetery.

“It’s part of a wall covered over with cement. We don’t even know which part of the wall it was put into. It could even be the foundation of the wall,” said Barbara Fash, director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology’s Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program. “We no longer even have the original monument any more.”

Though the stele itself is gone, its story has not been lost. Its inscriptions have been preserved in a long-neglected collection of plaster casts of Maya and Aztec monuments whose value scholars have increasingly recognized in recent years.

These casts – roughly 600 of them – were made in the field at a wide variety of sites in the late 1800s and early 1900s. At the time, they were considered a poor second choice to securing the original, a step above a photograph.

But as time, looters, acid rain, and the normal weathering of the years have taken their toll on the originals left in the field, scientific sensibilities have changed. It is no longer acceptable to remove original monuments from their home countries, making reproductions like the casts more valuable to far-away museums.

But it is the information the casts contain, increasingly lost on the originals to vandalism and the ravages of time, that has catapulted them upward in value for those struggling to understand the lost Maya civilization through the histories told by the Maya themselves on these monuments.

The Peabody Museum’s Corpus program, led by Fash, is at the forefront of a new movement to recover and preserve the knowledge the casts contain, knowledge that would otherwise be lost forever in the jungles of Central America.

“We have about 600 casts from about 16 different sites – Maya and Aztec … . All of these monuments have details that are now eroded on the originals. All of them,” Fash said.

Steven LeBlanc, director of collections at the Peabody Museum, said the preservation and study of the Maya casts is a good example of the role that museums play in preserving knowledge for future generations.

“When these were originally collected and brought to the museum they could not be read. Now that the hieroglyphs can be deciphered, the casts are more valuable than anyone could have imagined,” LeBlanc said. “Museums collect and curate many things that do not have obvious value now, but as has happened repeatedly, they may be of great importance in the future.”

Over the past decade or so, the first order of business has been to preserve the casts themselves, Fash said. They had been stored haphazardly, some black with soot, others chipped and cracked, stacked along the walls several deep in the large Peabody Annex behind the museum. A few years ago, Fash, Harvard students, and Peabody Museum conservators began the painstaking process of cataloging and cleaning the casts – water can’t be used because it will dissolve the plaster.

They’ve also designed and begun building custom rigid polycarbonate cases with metal edges, to protect the casts and allow them to be stacked, stored, and accessed more easily and safely. Though some cases have already been completed, the process will be a long one, Fash said, because of the size of the collection.

The potential payoffs of their work are many, however, to scholars, to the museum, and to the home nations where the original monuments stand.

In some cases, the Peabody has made copies of its casts and sent them to the monuments’ home countries. This allows officials there to take the fragile originals off public display and put out the cast copies, which often are in better shape and have more details than the original, Fash said.

“It’s sad, because at so many of the sites that have beautiful monuments and historically important monuments, [country officials] can’t always take care of them because preservation in the field is hugely problematic,” Fash said.

Jeffrey Quilter, the Peabody’s deputy director for curatorial affairs, said Fash’s work with the casts has not only helped preserve a unique resource, it has also strengthened links with Latin American colleagues.

“Barbara Fash’s work with the casts is exemplary in its combination of helping to preserve a unique Harvard resource, researching the past, and informing students and the public. Equally important, her work has forged stronger links with colleagues in Latin America,” Quilter said.

Exactly when many of the casts were made is unknown, Fash said, because the researchers considered them of lesser importance at the time. Many were made more than 100 years ago by moistening paper and pressing it around the shapes on the original monument, building up layer after layer until they’d created a solid mold. A fire was lit nearby to dry the paper, after which it was removed from the monument and then packed out of the site in what appear, in photographs of the time, to be comically large backpacks.

Back at the Peabody, the molds were used to make plaster casts of the monuments, Fash said, adding that they are re-usable up to three times before details begin to get lost. The paper molding process has been little-used for some time, since the advent of latex to make molds with.

The Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions is moving beyond latex, however, and employing modern technology in its efforts to preserve the Maya monuments and the information they contain.

said they’re in the final stages of testing a laser scanner that creates a digital, three-dimensional image that can be stored on a computer. The image can be “printed out” when needed using a device that builds three-dimensional models, layer by layer, using the stored image files.

said they’re in the final stages of testing a laser scanner that creates a digital, three-dimensional image that can be stored on a computer. The image can be “printed out” when needed using a device that builds three-dimensional models, layer by layer, using the stored image files.

The process has been successfully tested on samples in the Peabody’s collection. Fash said that plans are being drawn up for a team to go to Yaxchilan, a Maya site in Chiapas, Mexico, in March to field-test the system. If everything works as planned, Fash said, the Peabody will begin regular trips to laser-scan as many monuments as possible, creating a digital record to augment the originals, casts, and photographs in the collection.

The new technology is a potentially powerful tool in re-creating Maya monuments, Fash said. In addition to being able to scan an original monument – or a cast – to make a three-dimensional image, they can also input photographs taken of the original at the time of its discovery. Museum archives have 50,000 photographic images, some of which contain lost details that the computer can combine into new three-dimensional images that transport a damaged monument back in time.

When it comes to Maya hieroglyphics, details count, Fash said. Small dots and squiggles on the original monument matter when reading the complex script, which is still being deciphered today.

“Every detail is important,” Fash said.

To call attention to the Peabody’s collection, a selection of casts made from 14 lost Maya and Aztec monuments have been on display since 2001. One, from Piedras Negras, was instrumental in helping scholars decipher the Maya’s written language, a process that is continuing. Today, however, the monument itself has been broken into pieces and scattered.

“Looters took to the monument and carved pieces off. It’s no longer in one piece. It’s not even known where all the pieces are,” Fash said. “Now that we’ve made great advances in the decipherment process, epigraphers can come here and look closely at our casts and see details that they can’t see on the original. And they don’t have to cut through the jungle to get here.”

Related links:

- Oldest Mayan mural found by Peabody researcher: Jungle ordeal leads to surprise treasure

- Three weeks in tiny tunnel pay off: Maya creation mural makes toil worth the trouble

- Pathway to the Past: Mayan staircase project preserves ancient history