Seven Harvard students named Rhodes Scholars

Harvard has the highest number of winners

Harvard students and a recent graduate won seven of 32 Rhodes Scholarships awarded to Americans for 2007. The scholarships provide all expenses for two or three years of study at the University of Oxford in England, worth an average of about $45,000 a year. The 32 winners from the United States will join an international group chosen from 13 other nations and jurisdictions, extending from Australia to Zambia, Bermuda to Botswana. This year, Harvard has more Rhodes Scholars than any other school. The scholars will enter Oxford in October.

The oldest and best-known scholarships for international study, the awards were created in 1902 by the will of Cecil J. Rhodes, British philanthropist and African colonialist. It was his hope that the scholars would make effective and positive contributions toward a better world. Rhodes Scholars should, he wrote, “esteem the performance of public duties as their highest aim.”

Loving literature, sharing the passion

Joshua Billings, a senior majoring in classics and German, was drawn to an academic life by a passion for literature and teaching. “I’ve always loved literature, particularly Greek and German literature, and wanted to study the interaction of the two,” he says.

By his junior year in high school, Billings had already started down that path. He spent two summers teaching both literature and mathematics full time to fifth and sixth graders in public schools in Cambridge, Mass., his hometown. “That program, called Summerbridge, was my most meaningful experience outside my high school classrooms,” he comments.

At Harvard, Billings produces and directs student operas. “One of the most fun of my college experiences,” he calls it. He also is chief editor of the Harvard Book Review. All this and classes don’t allow much time for recreation, but when he gets time, he likes to read and cook.

Billings describes his selection as a Rhodes Scholar as “a very high-pressure process.” It ended at an interview in New York City, when he was told that he had won the honor. “At first, I was surprised,” the Leverett House resident recalled. “There were a lot of extraordinary people in the competition. Then I felt happiness. I’m very lucky.”

At Oxford, Billings will study European literature. “I’m excited about being in the community of Rhodes Scholars,” he says. “I look forward to studying with people from all over the world.”

A writer’s life

For her senior thesis, Casey Cep is writing a novel, an indication of how seriously she takes her work as a writer. Other indications include the fact that she is president of the Harvard Advocate literary magazine and an editor at both the Harvard Crimson and the Harvard Book Review. In addition, she has interned at The New Republic.

Cep credits Harvard’s stellar community of writers and critics for her development and said she hopes to work as a writer, either in literature or journalism, after completing her studies at Oxford.

“It’s just a tiny part of the world with an unbelievable gathering of writers and critics,” Cep said of Harvard. “Harvard has been an extraordinary place to go to college.”

The English and American literature and language concentrator and resident of Pforzheimer House plans to study theology at Oxford to both feed a longtime personal interest and to gain insight to a force that is a powerful motivator in people’s lives.

Motivations of people and characters are important for a writer. Cep’s novel, “Tributaries,” is set in her native Maryland Eastern Shore, where she grew up fishing and crabbing in the small town of Cordova. The book, she said, explores how four siblings deal with the grief over their mother’s death. In addition to exploring the characters’ journeys, she said the book also explores the unique community and way of life Chesapeake Bay’s Eastern Shore offers.

“I’ve always been interested in small niche communities where people are very familiar with each other,” Cep said.

When she leaves Oxford, Cep plans to return to the Eastern Shore region and use her writing skills in some way to give back to a community that she feels gave her so much.

A scholar and activist

It was all about politics when Brad Smith was at Harvard as an undergraduate government concentrator and it’s still about politics for Smith.

Smith, who graduated in 2005, was active in the Institute of Politics (IOP) while at Harvard, working on an IOP student advisory committee on Social Security reform. His work with the group led him to testify on Social Security privatization before the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging. He also chaired the Massachusetts Alliance of College Republicans.

Smith put his Harvard experience to immediate good use, working through November’s election on the successful U.S. Senate campaign of Republican Bob Corker in Smith’s native Tennessee (he hails from Chattanooga).

Smith performed many tasks for Corker’s campaign, traveling with him across the state, helping set up appearances, conducting research, writing memos, and eventually handling some logistic and press issues.

After months of 14- to 16-hour days, Smith is now working on Corker’s transition team, but he expects his work for Corker to stop in January when Corker is sworn in and Smith begins to look ahead to next year at Oxford.

Smith says he feels blessed by his selection for the Rhodes Scholarship, particularly because after meeting the other finalists in his district, he felt any of them could have gotten it.

“I was really surprised,” Smith says. “You go and there are so many good candidates. I could see all of the others getting it.”

Smith says the first person he called to tell the news was his father, whom he phoned from the car after leaving the final interviews.

He plans to pursue an M.Phil. in comparative social policy at Oxford and continue his political work when he returns to the United States, working as a campaign manager or policy adviser either in Tennessee or national politics.

Better living through chemistry

Parvinder S. Thiara intends to work toward increasing the world’s supply of clean water. A senior majoring in chemistry, he was drawn to this goal by the death of his grandfather, who succumbed to infectious diarrhea in India. “Water is a big problem,” Thiara says. “I found that more than 2 million people, most of them children, die each year from waterborne diseases.”

Thiara founded the nonprofit Foundation for the Advancement of Water Sanitation Improvement Technology. “We’re trying to identify and develop natural products that can be processed locally and used to disinfect water,” he says. “For example, we have been working with clove oil, which shows promise in this area.”

Thiara, a Kirkland House resident, works in the laboratory of Eric Jacobsen, the Sheldon Emery Professor of Chemistry, and in his junior year he was elected to the national honor society Phi Beta Kappa. At Oxford, he plans to earn two master’s degrees, one in theoretical chemistry and the other in water science, management, and policy.

For recreation, Thiara is fond of Bhangra dancing, which he describes as “a traditional folk dance that has been modernized to become the hip-hop of India.” He is from Rochelle, Ill.

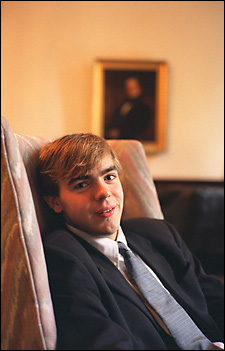

While overseas, Ryan Thoreson ’07 will study for an M.Phil. in social anthropology, a pursuit that will allow him to explore the cultural context of international laws on gender and sexuality. (Staff photo Kris Snibbe/Harvard News Office)

Giving something back

Ryan R. Thoreson ’07 is a playwright (“Fargo, A Mostly True Story”), an activist for sexual civil rights, senior editor at Perspective magazine, and a blogger for Cambridge Common and Dem Apples, an organization of Democrats at Harvard.

Now the 22-year-old is a Rhodes Scholar, too. “It was really nice to step back and reflect on everything I had done at Harvard,” says Thoreson of the process, which required a 1,000-word personal statement on an imagined course of study at Oxford. “There’s not that much opportunity to reflect. Whether or not I got the Rhodes, it made me think about my life a little more.”

After a 15-hour road trip with his mother from his home in Fargo, N.D., Thoreson on Saturday (Nov. 18) found himself in a conference room in Des Moines, Iowa, with 15 other Rhodes finalists – for 10 hours. Each one had a 20-minute interview, and a long wait. By 5 p.m., Thoreson got the news that changed his life. “I was shocked more than anything else,” he says – in part because of the diversity of his District 14 competitors: student experts in tropical medicine, conservation, political theory, and more.

The Rhodes Scholarship itself caught his eye because it required “giving something back to society and the world,” says Thoreson. “It was a vehicle for change.”

Prompting change is something that right along has inspired the Lowell House resident, who has joint concentrations in government and in studies of women, gender, and sexuality. He is active in the Harvard Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, and Supporters Alliance and coordinates the Alternative Spring Break AIDS Action Project. (It distributes meals to an HIV/AIDS population in New York City.)

After Oxford, Thoreson will pursue a career in international law, with an emphasis on civil rights law as it applies to sexuality. “I have a stack of (law school) applications on my desk,” he says. “I’ll push them off now until my second year at Oxford.” While overseas, Thoreson will study for an M.Phil. in social anthropology, a pursuit that will allow him to explore the cultural context of international laws on gender and sexuality.

Last summer, as a Weissman International Intern, Thoreson worked at the International Lesbian and Gay Association, a nonprofit in Brussels, Belgium. In some countries, he discovered, the sexual civil rights issues being fought over in the West – marriage, adoption, employment law – can take a deadly turn. In Iran, Morocco, and elsewhere, anti-sodomy laws are explicit. In China, homosexual men and lesbians are often prosecuted as hooligans.

Thoreson will write his honors thesis on the gay and lesbian civil rights movement in South Africa. The one-time home of Cecil Rhodes, he says, provides a role model for the world in terms of sexual civil rights. It’s a country where, under apartheid as little as two decades ago, homosexuality was banned – and where this year a law was passed legalizing gay marriage. Says Thoreson, “They went from zero to 60.”

Championing the marginalized

Elise Wang ’07 is too busy today to think about being named a Rhodes Scholar: She’s studying for a midterm in the history of American revolutions. But being busy is nothing new for the 22-year-old Chicagoan, who transferred to Harvard after her freshman year at the University of Pennsylvania. She was coxswain for two crew teams, one at the John F. Kennedy School of Government and the other at Adams House. She played the violin and viola for the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra. And she took a year off to travel in Taiwan and to study Mandarin, immigration issues, and Chinese history at Beijing University.

Being busy will mark the next six months, too. Wang, a bilingual concentrator in studies of women, gender, and sexuality and comparative religion, will write an honors thesis on conceptions of feminism and faith in modern literary treatments of two Chinese empresses. She’ll also finish writing a legal handbook for the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women.

At Oxford, Wang will pursue an M.Sc. in forced migration, an interdisciplinary look at the legal framework of refugee law and the causes that underlie migration patterns. For immigrants, says Wang, who volunteered one summer at a law firm that represented undocumented workers, “everything is 10 times harder.” After Oxford, she will pursue a career in immigration law, inspired, in part, by her father’s story. A trained pathologist, David Wang emigrated to the United States from Taiwan in 1982 – the first member of his family of farmers and soldiers to graduate from college.

As for winning the prestigious Rhodes, says Wang, “Every step of the way was a gift.” Being nominated, being a finalist, bracing for the last interview in Chicago, then waiting a final few hours with eight other candidates. (Only Wang and one other of the group were awarded the scholarship.) “There was absolutely no way to tell who would win or why they would win,” she says, eager to dispel the idea that the final winners stood out from their nominated peers. “Every single person I met was idealistic, earnest, and completely sincere, in addition to be overwhelmingly qualified.” Adds Wang, “I felt perfectly OK with any of us winning it.”

Someday, she says of her new Rhodes competition friends, “I’m going to read about them in The New York Times.”

Children’s advocate

Daniel Wilner ’07, a philosophy concentrator from Kirkland House, sees a strong connection between his love of the theater and his intention to work on childhood development in the future.

Wilner, a Montreal native and a Canadian Rhodes Scholar, worked with refugee children last summer with the International Rescue Committee in New York. He says working in the theater and with children both require one to be spontaneous and open to the world around you.

Wilner, who credits Harvard with giving him “strong intellectual tools” with which to move ahead, plans to study politics and social policy while at Oxford, though his specific plan of study is yet to be finalized. In addition to his academics, Wilner has done considerable work in theater while at Harvard, including work with the Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club and with a theater company in Paris. He looks forward to participating in the student drama scene at Oxford and hopes to continue acting for several years after completing his studies.

Ultimately, however, Wilner says, he plans to work in child development, with the aim of strengthening societies’ policies toward children. One possible route, he says, is to enter medical school with the intent of specializing in child psychiatry.

He’d one day like to work with institutions and influence them to adopt policies that help children become creative individuals. Today’s educational system, he says, seems to regard art and athletics as luxuries that can be cut when budgets get tight. That underestimates the impact those two activities can have on a child’s development, he says.

“In some ways education is making children less creative when it should be doing the opposite,” Wilner says.