Little Lulu comes to Harvard

The Little Lulu papers have found a home at the Schlesinger Library.

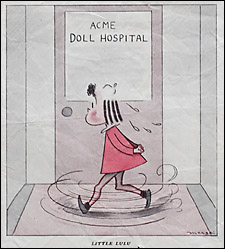

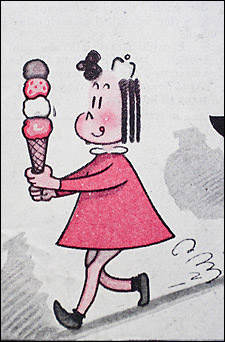

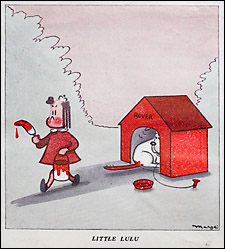

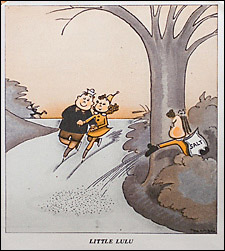

One might wonder why this cartoon character with her button eyes, sausage curls, and frilly bloomers peaking out beneath the hem of her bell-shaped red dress deserves a place beside the likes of Emma Goldman, Amelia Earhart, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. But as her boyfriend Tubby often found to his chagrin, Lulu is no one to trifle with … or ignore.

According to Lawrence Buell, the Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Lulu’s feistiness and independence have a significance that transcends the world of cartoon characters of which she was part.

“Lulu seems to me to be of great historical interest as a barometer of young women’s assertiveness in a male-dominated culture,” Buell said.

Buell, whose normal area of expertise encompasses Emerson, Thoreau, and other figures of 19th century American literature, is specially qualified to speak with authority on Little Lulu. His mother, Marjorie Henderson Buell, created the cartoon character in 1935. This year, Buell and his brother Fred Buell, professor of English at Queens College of the City University of New York, gave their mother’s papers to the Schlesinger, America’s premier library of women’s history.

Lulu will hardly be out of place there. Her creator was the first female cartoonist in the United States to achieve worldwide success. Little Lulu has appeared as a syndicated newspaper strip, in comic books, animated cartoons, and as a spokesperson for Kleenex. And she has been translated into many languages including Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, and Japanese.

“At one time, Little Lulu was second only to Disney in terms of sales and visibility,” Buell said. “But my mother made a decision to remain a small contractor rather than become a fast-track entrepreneur. She used to speak of her success in tones of wonder and bemusement.”

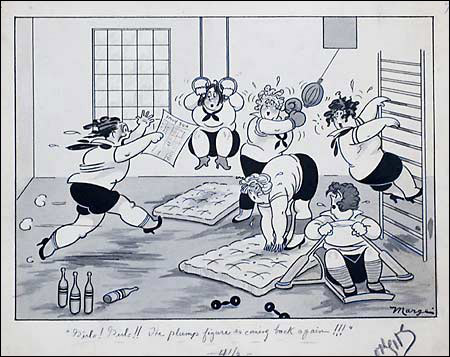

Born in 1904, Marjorie Henderson Buell was the product of what might be called a classic American childhood. She grew up in a small town outside Philadelphia and was homeschooled until the age of 11 or 12. One of three artistically talented sisters, she drew and painted as a child and sold her first cartoon to the Philadelphia Ledger at the age of 16.

By the time she was 25, she was publishing her first syndicated comic strip, “The Boyfriend,” under the name “Marge.” Her first Little Lulu cartoon, a single-panel drawing, appeared on the last page of the Saturday Evening Post in 1935. This initial version of Lulu was a bit more elongated than the character’s later image, but Lulu’s mischievous, insouciant personality was there from the start.

Over the next few years, Lulu’s popularity grew rapidly. Her adoption as an icon for Kleenex put her image on billboards and in magazines. A syndicated newspaper strip and monthly comic books chronicled her adventures, and a series of animated cartoons by Paramount brought Lulu to the movies.

“By the time I was able to take stock of the world, Little Lulu was already an institution,” said Buell, who was born in 1939.

Buell said that growing up with a celebrity mom was “kind of fun,” although at times it could be mildly embarrassing. Long and lean as an adult, Buell confessed that as a child he was “on the porky side.” As a result, he sometimes got teased about being the model for Tubby.

As Buell and his brother got older and more aware of events in the outside world, they began to urge their mother to take Little Lulu in new, socially progressive directions. But they found that their mother had her own ideas about what was appropriate for her creation.

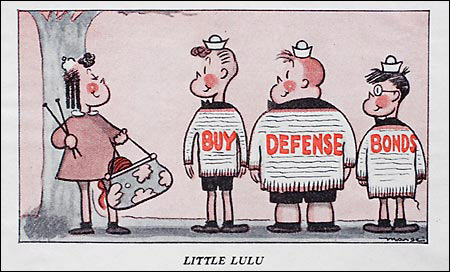

“In the late 1950s, my brother and I tried to advocate that the cartoon be integrated, that my mother needed to add a black playmate for Lulu. But she didn’t think of Lulu as a part of politics. She drew a line between entertainment and didacticism.”

Nor did Marge welcome the idea of introducing feminist themes into the cartoon. She preferred to let the character’s actions speak for themselves.

“She created this feisty little girl character who held her own against the guys and frequently outwitted them, but she didn’t want to turn the cartoon into a message. She agreed with Samuel Goldwyn’s slogan, ‘If you want to send a message, try Western Union.’”

And while early photographs of Marge show her to be an impish little girl with black curls, she also rejected the suggestion that the cartoon character was based on herself.

“My brother and I thought that Little Lulu was a self-caricature, but she resisted that too. She didn’t want to reduce the cartoon to an autobiographical subtext.”

His mother’s reluctance to embrace meanings or agendas that others found in her work may have had a significant influence on Buell’s ideas about literary criticism. It showed him that what an artist says about the origins and purpose of a work should not necessarily be granted a privileged position in its interpretation.

“The public will take the work in directions that the artist won’t have consciously intended,” Buell said.

Buell learned something else from growing up as the son of a highly successful artist – the importance of negotiation and compromise in a two-career marriage.

Buell’s father was an executive at Bell Telephone of Pennsylvania, an ambitious and successful man who worked his way through college at the University of Pennsylvania. But in order to ascend to the top echelons at Bell, he would have had to follow the customary career pattern of periodic relocations, something his wife was unwilling to accept.

Buell remembers his parents discussing the matter and eventually reaching a compromise. His father would trim his career ambitions in exchange for providing a stable locale for his family. His mother likewise would turn down the chance to pursue a Disney-style media empire and would instead be available for her children, at least when she was not working in her studio.

“For me it was a pretty powerful model of the importance of both partners negotiating their goals together,” Buell said.