Kennedy School, Law School students labor for Nairobi poor

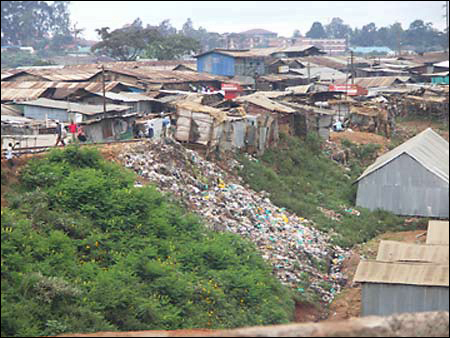

Nairobi’s Kibera slum is home to as many as a million people, struggling to survive in a community of tin huts, dirt roads, and garbage. To make matters worse, ethnic tension periodically boils over, adding violence to Kibera’s toxic stew of poverty, AIDS, and despair.

Two Harvard graduate students are working to bring hope, health, and a little soccer to the slum, through a nonprofit organization one of them founded. The organization empowers local people by giving them the tools and support needed to improve their community and their lives.

Carolina for Kibera Inc., or CFK, was founded by Rye Barcott – a joint M.P.A./M.B.A. student at the Kennedy School and Harvard Business School – after he spent the summer of 2000 in Kibera studying ethnic violence.

By the end of that summer, Barcott knew he couldn’t just walk away from the conditions he saw there without trying to do something. Inspired by an athletic league in the nearby slum of Mathare, he began to plan a similar athletic venture with the help of a Kibera resident, Salim Mohamed.

The league, Barcott hoped, would bring youth of different ethnic groups together as teammates, helping bridge differences between their communities. In addition, Barcott said, the youth who played would do community service, cleaning up garbage and working to make Kibera more livable.

As the summer wound down, Barcott got ready to head back to his studies at the University of North Carolina and made plans to raise money for the athletic league. But Kibera wasn’t quite finished with him.

One day, Tabitha Festo, a nurse familiar with Barcott’s work for the athletic league, asked him for a small amount of money to begin a health clinic. At first skeptical, Barcott soon became convinced Festo was sincere and gave her the 2,000 shillings – $26 – she asked for. It was something of an act of faith for Barcott, since he didn’t know for sure what would become of the money or whether he’d see Festo again.

Back in the United States, Barcott spent the school year trying to raise money for the athletic league. It turned out to be much tougher than he expected, but he managed to bring in about $20,000. He returned to Kenya the next summer and, working with Mohamed, got the league going.

He also got to see the fruits of Festo’s labor. Since Barcott had left Kenya the previous fall, Festo had used the seed money he’d given her to buy vegetables cheaply in a neighboring community and sell them for a higher price in Kibera, turning the $26 into $100. She used that money to open a small one-room clinic. Barcott said he found out about the clinic when Festo took him by the arm one day and led him to a red-painted building with a “Rye Medical Clinic” sign on it.

The clinic – renamed the Tabitha Medical Clinic – soon joined the athletic league under CFK’s umbrella and has grown rapidly to meet the area’s need for health care services. From seeing just five patients a day when it started, the clinic today has two doctors on staff and sees about 150 patients a day. CFK has continued to grow to meet Kibera’s needs in the intervening years. Today the league and clinic are joined by an AIDS and reproductive health awareness center for teenage girls and a garbage recycling program. A nursery school, also established through CFK’s efforts, has become independent.

Matt Bugher, a first-year student at Harvard Law School, serves as CFK’s treasurer. Bugher said he was an undergraduate at Grove City College in Pennsylvania in 2002 and was looking for a chance to work in Africa when he came across CFK’s Web site. He wound up volunteering with CFK that summer and by January 2004 had become the organization’s treasurer.

“It was amazing,” Bugher said. “It was really shocking at times and it was hard. It made going back to college and studying business hard.”

Bugher’s experience in Kibera prompted him to change his plans to go into business. Instead, he is studying law with a focus on human rights.

Bugher, like Barcott and CFK’s eight other U.S.-based staff members, are volunteers. Though the organization is Barcott’s brainchild, he sees his role today as one of support. From the start, Barcott said, he felt he had as much to learn from Kibera residents as they had from him. Anyone who can live on a dollar a day has to be resourceful, he said. The day-to-day operations are currently handled by 20 Kenyan staff members working in Kibera.

That hands-off management style is partly because Barcott believes that the organization will ultimately work best if run locally, but also partly because Barcott was busy in the Marine Corps during CFK’s early years.

Having gotten through the University of North Carolina on an ROTC scholarship, Barcott served as a captain in the Marine Corps after graduating, including a year in Iraq from September 2005 until August 2006, when Barcott left active duty. Barcott said he did little hands-on managing during that time, but continued to fundraise and offered moral support for those struggling with day-to-day decisions.

“When other Marines were writing to mom, I was writing to donors,” Barcott said.

Today, Barcott said, CFK serves roughly 25,000 people and was recognized by Time Magazine in 2005 as a “Hero of Global Health.” Barcott himself was recognized by ABC News in October as its “Person of the Week.”

When asked how the organization today matches his expectation when he started it, Barcott responded: “It blows it out of the water.”

“I thought I’d go raise some money, inject it, and go on with my life as a Marine,” Barcott said. “But it has become like an extended family.”