‘Human Factor’ at HBS shows industrial, business photos

From the front steps of Baker Library at the Harvard Business School (HBS), you can see the ever-moving present: the glitter of traffic along Soldiers Field Road, the gliding Charles River, and, beyond the Weld Boat House, the distant bustle of Harvard.

To see the past – itself ever changing, and fascinating – just turn around and enter Baker’s North Lobby. On view through early March is “The Human Factor,” an exhibit of pictures that celebrates the surprising art and compelling documentation of industrial photography assembled by HBS between the world wars.

The 57 images in the show (and more on the Web site) are just a fraction of the 2,100 pictures collected during the 1930s by HBS colleagues Donald Davenport and Frank Ayres. The two men wrote to 115 companies, asking for photos that would capture, as Davenport put it, “the courage, industry and intelligence” of the American worker.

For years, the photos – scenes of industry from the 1920s to the early 1940s – were trotted out for classroom work, or for HBS exhibits.

“The Human Factor” is the first of a series of photography shows at Baker Library that over the next few years will introduce scholars and the general public to the full range of HBS’s extensive, and little-known, collection of 30,000 industrial and business photographs.

The title of the present exhibit refers to the interest Davenport and Ayres had in the interaction of worker and machine – “the human factor” of industry that they thought was little understood in the classroom.

HBS “believed photographs of workers and machines would be valuable records for study in industrial management classes,” said Melissa Banta, guest curator of “The Human Factor” and a Harvard photo archivist and historian. “But these images were coming from public relations departments interested in employing photography as a way to convey a message of corporate success.”

For companies, the Davenport-Ayres request for photos represented an opportunity to celebrate American goods manufactured during the Great Depression, when consumer confidence in both the products and the uses of capitalism had to be restored.

The 1930s was also a decade in which both advertising and industrial relations were becoming more sophisticated, and taking on a scientific tenor. (In that era, HBS doubled its industrial relations course offerings.)

“Companies were eager to demonstrate the effectiveness of their industrial operations and most likely wanted to be sure they had a presence beside their competitors who were donating images to Harvard Business School,” said Banta. “The venue also offered businesses a chance to appeal to an upcoming generation of corporate administrators and potentially future managers of their companies.”

The ’30s were a rich time for photography as an art form. Banta points out in her essay for the exhibition catalog that the photos on display in “The Human Factor” took inspiration from some art movements, including cubism. Many of the photos were shot by famous photographers who were social activists, photo journalists, and photo artists.

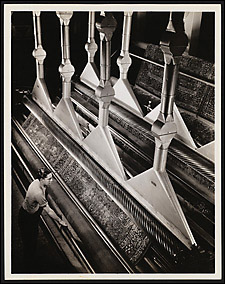

Margaret Bourke-White, one of the original photographers for both Fortune and Life magazines, found her earliest pictorial inspirations in industry and architecture. In “The Human Factor” there are examples of her artful documentation of electroplating and steel making. Her 1934 photo “Belting the Tines” records a process, the polishing of silver forks. It also transforms this close-up of hand labor into a work of art that is wavelike and fluid.

Lewis W. Hine, an investigative photographer who sometimes recorded the dark side of factory work, also created grand and hopeful photo documents of industry, including the building of the Empire State Building. Examples of his work for Shelton Looms, on exhibit at Baker Library, are intimate portraits of laborers in a long-ago world of factory cloth and carpets. His 1933 “A Finisher” draws the viewer into the intense effort of a worker framed by chains and gears.

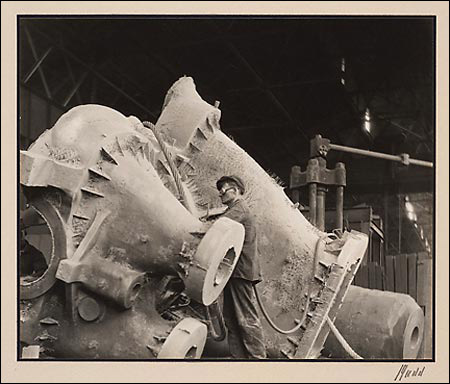

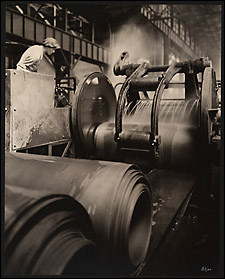

The exhibit is also a stop-motion look at industry between the wars. Its black-and-white images evoke the past the way an old movie might. The photos – many drawn directly from company promotions – show the romance of labor, the gigantism of industrial machinery, and the Oz-like shininess of staged factory activity.

There’s also the jarring shock of scale. Two men in soft caps, circa 1937, work inside a house-size General Electric Co. turbine. In a 1932 photo from the Carnegie-Illinois Steel Corp., a man with arms raised looks improbably tiny next to a giant cauldron pouring ingots of molten steel.

Some of the Baker Library photos capture the crisp symmetry of industrial labor. In a California packing house, straight lines of women work in nunlike white gowns, boxing apples. In another photo, uniformed women perch on stools in orderly rows, cracking eggs for mayonnaise. The image has the clocklike precision of a Busby Berkley chorus.

Examples from the Davenport-Ayres collection were chosen for the first HBS photo display because they span so many industries and capture so many interactions of worker and machine, said Laura Linard, director of historical collections at the Baker Library.

But the collection is not only a visual record of long-vanished process and procedure, she said. “Beautiful photography comes out of this.”

Future photography shows at the Baker Library will draw on a plethora of historical documents, including photographs that record industrial practices in North, Central, and South America. One collection alone, a compilation of United Fruit Co. photographs from 1891 to 1962, consists of 10,000 images.

Other photos record automobile promotions (1931-1944), Pan-American industries (1913-1934), and the tea trade in China. There is even a collection of Caterpillar tractor images (1927-1932).

“We’re very interested in making people aware of the extent and scope of the photographs,” said Linard. Beyond pictures, she keeps track of HBS’s 350,000 rare books and the manuscript and archival collections from the 16th century to the present day.

Baker Library is just one of nearly 50 repositories of historical photographs at Harvard that together house nearly 7.5 million images.

“There are many hidden photographic treasures at Harvard,” said Banta, whose work as a curatorial associate at Harvard University Library’s Weissman Preservation Center brings her into contact with collections all over the University. “And there’s an increasing focus on making them accessible, and interpreting them in new ways.”

‘The Human Factor: Introducing the Industrial Life Photograph Collection at the Baker Library’ is free and open to the public through March 7. Exhibit hours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday; noon to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday.

For a look at the exhibit online, go to http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/hf.

Gallery talks featuring Melissa Banta are offered at 4 p.m. Jan. 18 and at 4 p.m. Feb. 8.