Three-day extravaganza fetes Bernstein

The maestro and the Kroks: Bernstein goes a cappella

Sixty years ago, as a junior at Harvard, Leonard Bernstein ’39 already had a reputation among undergraduates for his precocious performances with the Works Progress Administration orchestra. He also cut classes, doodled instead of taking notes, and suffered unlikely lapses in scholarship. The future composer of wide fame got a “C” in at least one core music course.

Sixty years ago, as a junior at Harvard, Leonard Bernstein ’39 already had a reputation among undergraduates for his precocious performances with the Works Progress Administration orchestra. He also cut classes, doodled instead of taking notes, and suffered unlikely lapses in scholarship. The future composer of wide fame got a “C” in at least one core music course.

As part of a timeless college tradition, Bernstein also spent countless late nights at Eliot House discussing God, politics, and the arts “over plenty of beer,” said his old friend and fellow music concentrator Harold Shapero ’41.

But despite his outwardly typical undergraduate life, Bernstein “was all music,” said Shapero. At Harvard, he wrote scores, directed plays, edited music criticism, monopolized the piano at every party, and made his first appearance as a conductor, with incidental music for a 1939 student production of “The Birds.”

A recent three-day celebration at Harvard, “Leonard Bernstein: Boston to Broadway” (Oct. 12-14) explored the early influences on the man who was by mid-century the maestro to the world: His father Samuel’s singing; the rich music of his Roxbury synagogue; Jewish folk and liturgical music; amateur experiments with musical theater; a lineup of piano teachers (whose artistic lineage traces back to Beethoven); and the wider musical world of Boston that nurtured Bernstein’s genius.

“Boston to Broadway” was conceived two years ago and brought into focus by “Before West Side Story: Leonard Bernstein’s Boston,” a spring 2006 seminar that explored Bernstein’s musical roots in New England. “In the beginning, at least for Leonard Bernstein, there was Boston,” said seminar co-teacher Kay Kaufman Shelemay, G. Gordon Watts Professor of Music and professor of African and African American studies.

The seminar’s explorations evolved into “Boston to Broadway,” an intensive series of symposia (10), exhibits (three), and concerts (two) – an outsize event to capture the life and music of an outsize man. The recordings, video, and research from the 2005 seminar – along with videotapes of the recent festival – have been deposited in Harvard’s Edna Kuhn Loeb Music Library.

The event was part of a wave of new Bernstein scholarship, and drew a multifaceted picture of “one of the most celebrated and controversial” figures in American music, said festival co-director Carol J. Oja, William Powell Mason Professor of Music. Before becoming “a citizen of the world,” she added, “Leonard Bernstein was a son of Boston.” Oja helped plan the festival, along with Jack Megan, director of the Office for the Arts, and Tom Lee, program manager of Learning from Performers.

So over three days, the musical Boston of 60 and more years ago was at center stage.

Most powerfully, that Boston was the grand Congregation Mishkan Tefila in Roxbury, where on the Friday nights of Bernstein’s youth good music reigned, boosted by the second-best organ in the Northeast. And it was Sharon, Mass., where his parents had a summer house – and where Bernstein enlisted neighborhood kids in his early musicals, including a 1934 drag version of Bizet’s “Carmen,” with Yiddish dialect. (Bernstein, in a red wig and black mantilla, played the lead role.)

Bernstein’s musical New England was also the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, where he saw his first orchestral concert in 1932; the crosscurrents of jazz and American pop startling the airwaves and dance floors; and – of course – it was Harvard, where he wrote a sweeping thesis (in 62 pages) on the origins of American music.

And where he displayed his now-famous will. During a class in 16th century counterpoint, when Bernstein had defiantly composed and played a piece full of dissonance, he had an answer to his professor A. Tillman Merritt’s criticisms. Bernstein “took his fist, and banged it on the piano and said: I like it!,” Shapero recalled. “It was a demonstration of his conviction, a sureness that he had, and he needed – and that he was born with.”

The Bernstein festival – organized by the Department of Music and the Office for the Arts at Harvard – was framed just the way it should have been – with laughter and music at either end, and panels and symposia in between that had a Bernstein-like conversational energy.

On Oct. 12, the Bernstein family turned the John Knowles Paine Concert Hall into their living room, regaling a sold-out crowd with funny stories. “The Bernstein family was always a lot of laughs,” said Burton Bernstein, younger than Leonard by 14 years, and a onetime New Yorker staff writer. “A combination of very bad taste and hysteria.”

Nina Bernstein Simmons ’84, a filmmaker who helped digitize the Bernstein Archive at the Library of Congress, recalled a concert segment that her father – famously balletic and theatrical on the podium – conducted with just his nose.

Jamie Bernstein ’74, a writer and host of a series of Carnegie Hall Family Concerts, likes to remember her father disheveled and in a bathrobe, telling a joke.

Alexander Bernstein ’77, in a snippet from Nina’s film, “Leonard Bernstein: A Total Embrace,” said his father’s genius and good humor had a common source. “My father never grew up, entirely. He was very much a child, with that kind of curiosity, that kind of energy, and that kind of lack of boundaries,” said Alexander, now president of The Bernstein Education Through the Arts Fund Inc. “That had everything to do with his genius and with his accomplishments.”

In Bernstein family fun, nothing was sacred. Burton said the three Bernstein siblings invented a nickname for Mishkan Tefila Rabbi H.H. Rubenovitz: “Ha Ha.”

“We didn’t know how good we had it, in a way,” said Jamie of life with her famous father. “Every time you went to a concert, Leonard Bernstein was conducting.”

That night, a sold-out concert at Paine starred a dozen Harvard student musicians and the 29 Harvard Bernstein Festival Singers. “I had the time of my life working with these students,” said festival co-director Judith Clurman, director of choral activities at The Juilliard School and also one of the early planners of the festival. “I demanded a lot of them. Good is never good enough for me.”

The concert’s theme was the young Bernstein, and it included selections that early on inspired him: a composition by Mishkan Tefila musical director Solomon G. Braslavsky; works by Aaron Copland, Marc Blitzstein and George Gershwin; and Shapero’s “Four Hand Sonata for Piano,” dedicated to Bernstein in 1941. The show included the world premiere performance of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” as arranged by a teenage Leonard Bernstein in 1937 for a summer camp rhythm band. (Think ukuleles.) The score was unearthed during the 2005 seminar.

On Oct. 14, the 16th anniversary of Bernstein’s death, music and laughter closed the three-day festival. A “Celebrating Bernstein” concert in a nearly full Sanders Theatre sampled Bernstein’s mature work – with all the early influences (Jewish popular music, jazz, Gershwin) intact. There were selections from “Mass” (1971) and “Kaddish’ (1963), and bits of “Chichester Psalms” (1965), including the Hebrew version of a scatlike riff that landed on the cutting-room floor during the making of “West Side Story.”

The concert ended with two numbers from that legendary stage and screen production. There were two standing ovations.

At an earlier festival panel, an all-star cast had explored “West Side Story.” Attending were producer Harold Prince, who rescued the stage show when it needed funding; Marni Nixon, who was the soprano behind Natalie Wood’s singing in the movie version; and Carol Lawrence, who in 1957 created the role of Maria on stage. Lawrence provided a Bernstein moment, whirling artfully up to the podium like the dancer she still is.

The electric and intense score to “West Side Story” – part opera, part Shakespeare, part social commentary – “changed everything” in musical theater, said Prince. “First of all, it gave you courage.”

“We were controlled and manipulated by a genius,” he added. “We learned how to open new doors.”

At the festival, exposure to Bernstein opened new doors for the young Harvard singers and instrumentalists at the core of the celebration. Before long, said Clurman, the students paid the maestro the highest compliment: They added his music to their iPods.

After the Sanders Theatre concert, a reception was held at Eliot House. Alexander said the family had always wanted an event that showcased Leonard Bernstein as a great artist who was also a great teacher. The “Boston to Broadway” celebration of his father “exemplified that in every possible way – the scholarship, the artistry, and the teaching,” he said. “It was everything my father cared about.”

At the reception, the three Bernstein children – at the heart of events all week – were nearly the last to leave. They swept on their coats and piled out into the chilly evening. As they walked up Dunster Street they made their father’s favorite music – laughter.

“In our family,” Jamie had said earlier, “goofiness is next to godliness.”

The art and energy of young performers made the festival stand out among celebrations since the composer’s 1990 death, said Humphrey Burton, Bernstein’s biographer and longtime friend, who was a part of several symposia. “I haven’t been to something so fresh and youthful.”

Bernstein’s passion for teaching prompted his Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, which ran from 1958 to 1972. The same passion propelled him into television during the 1950s, when the medium was fresh and an open book for the arts. His TV work, highlighted in a festival evening of old kinescopes on Oct. 13, “showed his skill and range as a teacher,” said presenter Marie Carter, vice president of licensing and publishing at the Leonard Bernstein Office Inc.

In 1951, it was Bernstein’s dual love of teaching and the Boston area that led him to help found the music department at brand-new Brandeis University.

One young recipient of Bernstein’s wisdom was Glover Dale – now 71 – an original Shark in the stage production of “West Side Story” (1957-58). “I’m realizing it from this conference: My formative influences were Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein,” said Dale, who took part in an Oct. 14 “Dancing the Story” symposium. “One was tasked to point out your weaknesses; the other, to point out your strengths.”

Dale credits Bernstein’s deep empathy for changing his life. “You could feel that this was a man of heart,” he said. “That’s why he was such a great writer – because he was open. He tapped into what was in the room, in the world. He felt all of it.”

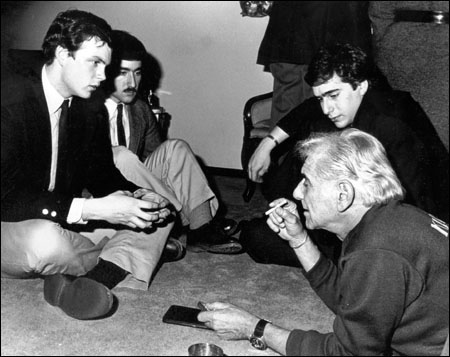

Devoted Krok Gordon Bloom ’82 (above, center) serenades the great master Bernstein (right) during the glory days of the group. (Photo courtesy of Gordon M. Bloom)

Bernstein felt for causes along the way, too, and marched for voting rights in the South and against the Vietnam War. But his sympathies never hardened into righteousness – despite his choral work for the radical and short-lived Harvard Student Union. (He directed the militantly unionist “The Cradle Will Rock” in his senior year.) “Lenny, though he had left tendencies, could never become doctrinaire in anything,” said Burton, “not even the Democratic Party.”

And his well-known sympathies for Israel never excluded the rest of the world. “Anywhere he went, he was in his element,” said Alexander of his father. “I traveled the world with him, and felt that very thing. What I got from him was a love of humanity, and making connections around the world.”

The last day of the festival was the anniversary of Bernstein’s death. “We don’t know how 16 years have passed since our father’s death,” said Alexander. “It feels like an injustice.”

But the Harvard festival took some of the sting out, said Jamie. “It’s been touching and gratifying,” she said. “The sheer attention lavished on our father and his life.”

The maestro and the Kroks: Bernstein goes a cappella

Leonard Bernstein ’39 wrote three symphonies, scored the breakthrough “West Side Story,” starred in early television, and swept his conducting baton over the world’s finest orchestras.

But in the fall of 1980, Leonard Bernstein also got on his hands and knees in a guest room of the Master’s residence at Lowell House and, starting with a low C, bellowed the call of the wild Sasquatch.

The occasion was his honorary, and spontaneous, initiation into the Harvard Krokodiloes, the University’s oldest a cappella men’s chorus. “This is great, this is Bernstein at his best,” Gordon M. Bloom ’82 remembers, thinking of the bellowing maestro. “This guy is really able to let loose.” That night, Bernstein had invited up a group of Kroks who wandered by his window, singing. Bernstein had also befriended the Kroks in 1973 (setting an e.e. cummings poem to music for them) while at Harvard delivering the Norton Lectures. But to Bloom’s early-80s iteration of the group, Bernstein was particularly generous and welcoming. He wrote them an original score (“Screwed on Wrong”), entertained them backstage at Avery Fisher Hall (home to the New York Philharmonic symphony orchestra), and hosted several Krokodiloes rehearsals at his home in the posh Dakota.

It was also Bernstein’s generous letter of recommendation that in 1982 helped launch the Krok’s first major international tour. (The group now tours five continents each summer.)

“Lenny had given us this letter, and it was like magic,” said Bloom, who now teaches at the John F. Kennedy School of Government and directs the Social Entrepreneurship Collaboratory at the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations. The brief typed missive, with Bernstein’s sweeping signature at the bottom, talks about “warmth, charm and comradeship.”

“Well, that was him,” said Bloom, one of generations of Harvard undergraduates affected by Bernstein’s grand gestures and generous teaching. “That was just him projecting his own sense of life onto the letter.”

When he coached the young singers, or just hung out with them to talk about the arts, it was often in a dressing gown, with a Scotch in one hand and a cigarette in the other. The periodic hours with Bernstein in Cambridge or New York “were a rollercoaster ride” of conversation, music, and parties, said Bloom – including a Bernstein-inspired 77th birthday performance by the Kroks for playwright Lillian Hellman.

Bloom remembers Bernstein best as a teacher, for his gifts of synthesis, challenge, and exploration. “His method was inspiring and transformational,” said Bloom, who uses the Bernstein touch in his own teaching, by blending traditional ideas with intuitive action. “You bucked the trend, you broke out.” The maestro also had a special empathy for students and performers suffering from insecurity. “Lenny had a way of just understanding that,” said Bloom, who to this day regards Bernstein as a mentor. “He made you feel like you could do amazing things. That was his gift.”