The pleasures and perils of pop culture

Preserving Ordway’s collection of pulp fiction at the Harvard College Library is a task that’s amazing! startling! wonderful! and … challenging

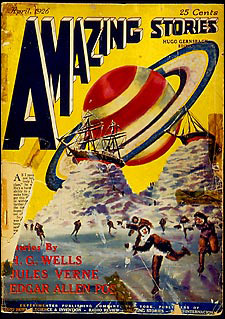

In the 1930s, years before man landed on the moon or even orbited the Earth, a very young Frederick I. Ordway III ’49 took an interest in space travel. One day Ordway returned home from school to find a copy of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories left by the family maid on a dining room chair. He raced to his room and read it cover to cover. Young Frederick wrote his parents a letter requesting the science fiction book “Lost on the Moon” for his 11th birthday. By the time he turned 12 he had joined the American Rocket Society as a student member. Before long, Ordway was a serious collector of science fiction, with a particular focus on the then-unmet dream of space travel. So intrigued was he that he joined pulp magazine fan clubs, actively acquiring duplicates and trading with other collectors.

In the 1930s, years before man landed on the moon or even orbited the Earth, a very young Frederick I. Ordway III ’49 took an interest in space travel. One day Ordway returned home from school to find a copy of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories left by the family maid on a dining room chair. He raced to his room and read it cover to cover. Young Frederick wrote his parents a letter requesting the science fiction book “Lost on the Moon” for his 11th birthday. By the time he turned 12 he had joined the American Rocket Society as a student member. Before long, Ordway was a serious collector of science fiction, with a particular focus on the then-unmet dream of space travel. So intrigued was he that he joined pulp magazine fan clubs, actively acquiring duplicates and trading with other collectors.

Decades later, Ordway’s personal collection mirrors what became a lifelong fascination. The boy who loved the idea of rocket propulsion and stories of space exploration grew up – after training in the geological sciences and working for a time in the petroleum and iron mining fields in South America – to be a real-life rocket scientist who worked for expert Wernher von Braun’s “rocket team” at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and later at the NASA-George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. This was the team that launched the first American satellite, Explorer 1, in January 1958 and the first American flight past the moon with Pioneer 4 in March of the following year. The same team put the nation’s first man in space aboard a Redstone-Mercury rocket in May 1961, and sent Apollo astronauts to the moon with the giant Saturn V rocket in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Ordway also authored, co-authored, or edited more than 30 books, wrote over 300 articles, and served as technical adviser to Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke for the 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

“I just knew what I wanted to do from a very young age,” said Ordway. “Those magazines put a spark under me.” His collection eventually became more sophisticated, venturing from sci-fi into astronomy and from 20th century magazines to books dating to the 1500s.

“I moved beyond them,” he said, “but I always loved the pulps.”

In 2002, Ordway donated his collection of approximately 900 science fiction pulp magazine issues dating from the 1920s onward to the Harvard College Library (HCL).

“I wanted to keep it all together,” said Ordway. “I was delighted to have it at Harvard – it made me very proud, very happy.”

For HCL, as well, the collection was a reason to celebrate. For a research library, the significance of the collection is twofold: It represents an uncommon glimpse of popular culture in the first half of the 20th century, and it presents a major preservation challenge.

The value of pop culture

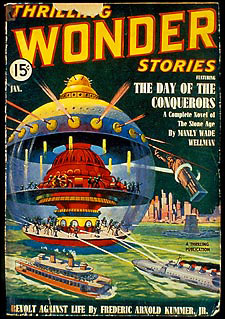

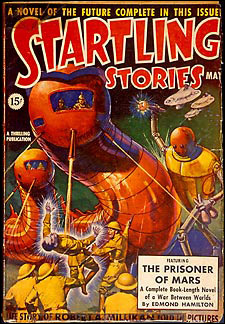

Ordway’s pulp magazine collection is many things: old, unique, intriguing. Filled with titles from the 1920s through the 1950s like Amazing Stories, Astonishing Stories, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories, it’s pure science fiction.

“It’s a collection about the engagement of intellect and spirit, science and imagination, work and fun,” said Alison Scott, Charles Warren Bibliographer for American History, Widener Library, who stewards the collection, “It’s the perfect way to build a collection. Ordway combined highly sophisticated technical professionalism with his interest in what is flat-out fiction, but on the same general topic.”

The collection features a lot more than fantastic stories and futuristic what-ifs. Each magazine, containing approximately 100 pages of imaginative fiction, ads, editorials, and letters to the editor, represents unadulterated pop culture, churned out quickly and cheaply. As such, it also provides a genuine look at race, class, and gender attitudes of the day.

“You’re not just seeing pure flights of fancy. You’re seeing minds embedded in their era working to construct imaginative fiction that is embedded in a particular time and place,” explained Scott. “In addition to stereotypes, you can get a more nuanced understanding of how people thought and felt and understood their world.”

The magazine covers – the only part of the publication in color – have their own eye-catching appeal, and some were created by the great American illustrators of the time, like Frank R. Paul and Earle K. Bergey. The covers are noteworthy for their “fantastic realism,” said Scott. “You don’t have models for space aliens. We’re not talking Rembrandt or Vermeer, but we’re talking about artists who gave visual terms to almost otherwise unthinkable visions.”

Research libraries are just beginning to collect popular culture materials like pulp magazines. “Professor Ordway’s very generous gift is one way to start filling that historical gap,” said Scott. “It’s also, I think, a potentially very important resource for students of American civilization, for history of technology, for history of travel and exploration.”

Popular culture at Harvard

One can’t always know how and when a library item will be used, but pop culture materials are being accessed more and more for research and teaching at Harvard. One example is a popular Harvard course, “Baseball and American Society, 1840-Present,” formerly taught by the late William Gienapp, which examined baseball’s relationship to the development of American culture. While Gienapp drew in part on baseball-related materials acquired by Widener Library over the course of the 20th century, the library specifically purchased many items to support the class and its students (although it was a large lecture class, the professor required every student to write a research paper).

According to Scott, who helped build the collection, Gienapp’s specific requests and the students’ inquiries demonstrated that just about anything relating to baseball – from statistics and sports writing in The New York Herald Tribune, to memorabilia catalogs and movies like “The Bad News Bears” – could turn out to be useful.

There are other cases of materials coming into their own. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the College Library had the opportunity to acquire a complete run of a women’s magazine from Cuba that dates from the early part of the century. At the time, the library wasn’t sure it should bother, but the risk paid off in the ’80s, when students started referencing the magazines’ stories and ads for thesis research regarding early feminist scholarship.

Then there’s the graduate student working on interracial relations and miscegenation in post-Civil War Louisiana who has used popular novels and movies like 1959’s “Imitation of Life” starring Lana Turner to explore its 20th century legacy.

Looking once again to science fiction, just last semester HCL acquired the TV series “Star Trek: Voyager” because an undergrad suggested it would be useful for a seminar paper. Finally, there’s the recent senior thesis that used color microfiche reproductions of “Golden Age” comics – some of the earliest comic books – for images of women.

The bottom line is that it can be hard to predict what researchers will find important. In the case of Ordway’s pulp fiction, its relevance wasn’t obvious to librarians in the 1930s and ’40s, but going back now and trying to piece together a collection item by item would prove incredibly difficult, which is why Ordway’s carefully assembled collection is such a boon for HCL – and the next time a researcher wants to study a little Astounding Science Fiction from 1940, he’ll find a solid dose of 20th century pop culture, perfectly preserved.

Preserving pulp

Pulp magazines came about in the late 1890s following the development of very cheap paper made from wood pulp, which helped make possible the mass production of magazines in large numbers. The Ordway collection raises its own preservation issues. Just as the pulp magazine’s research value grows with the passage of time, so unfortunately, does degradation of materials.

At the root of the problem lies acidity, which causes paper to darken and become brittle. The chemistry of aging lowers the pH of paper, according to Jan Merrill-Oldham, Malloy-Rabinowitz Preservation Librarian. Uncooked wood pulp paper exacerbates the problem, being already very acidic at the time of its manufacture. Furthermore, it still contains lignin, a component of wood that is chemically removed from refined papers.

Frederick Ordway III ’49, with a collector’s sensibilities, took good care of his pulp magazines, but that doesn’t resolve the problems posed by unstable paper. The question becomes how to preserve at-risk items. One timeworn but troublesome answer is to copy them, whether to paper, microfilm, or another format.

“We’ve been copying materials for centuries,” said Merrill-Oldham. “The scribes made slavish copies of manuscripts, for example. That’s the way that information was protected from loss and more broadly distributed. But it’s always been recognized that the copy is, just by virtue of being a replica, less desirable in some ways. It’s not the artifact. It’s a mirror of the artifact.”

Copyright also comes into play. By the time the copyright expires, the items in the Ordway collection, like many others, might be too brittle to handle, let alone copy. Copyright legislation grants a library permission to reproduce an item paid for and lost, or an item at risk of complete deterioration – but this doesn’t help the Ordway collection.

“With the Ordway material, if you looked at it right now, it would be hard to make the case that it’s deteriorating to the point where you have to copy it to rescue it,” added Merrill-Oldham. “And the copy would be a real shadow of itself, because it’s the genre you’re looking at, a type. It’s the nature of the paper. It’s the way the object has been bound, the way that it’s been printed.”

Because the collection was in good shape, but at long-term risk, Harvard College Library decided it made a good candidate to undergo the Bookkeeper mass deacidification process. Piloted in the mid-1990s by Preservation Technologies, a Pennsylvania-based company, Bookkeeper preserves paper-based materials by turning acidic pages alkaline. Small batches of materials are dipped (spraying is also possible) into a bath of nontoxic magnesium oxide, which is alkaline. The bath is continuously circulated during a two-hour treatment process to coat the materials evenly and filter loose dust and dirt, and, because the solution contains no water, the paper fibers don’t swell.

What emerges has a higher pH than went in, typically in the range of pH 8.0 to 9.5. In the weeks following the procedure, the magnesium oxide particles combine with moisture from the air to form an alkaline magnesium hydroxide buffer, which can absorb and neutralize acids in the paper. According to Preservation Technologies, it’s a permanent treatment, in which the materials continue to absorb acid over the life of the paper. Accelerated aging tests indicate that deacidification extends the paper’s life by three to five times.

Bookkeeper has been tested on inks and papers dating from 1870, and the Library of Congress has had materials treated, including 100,000 comic books from its collection. In a few cases, the shade of a color has been affected by the change in pH, but overall it’s a useful treatment and for far more than pulp fiction: Libraries are full of books printed in both the 19th and 20th centuries on good paper coated with alum and rosin so it would hold ink better. Unfortunately, alum, it turns out, is an acidic salt, rendering treated materials vulnerable to decay.

Of course, there is a caveat to deacidification. “It’s not a silver bullet,” said Merrill-Oldham. It doesn’t restore the paper’s strength nor can it save a book that’s too far gone. But it does stall decay, provided that treated materials are stored properly in a clean, cold, and dry environment – which is exactly how the Ordway collection will be stored in the Harvard Depository from where it can easily be recalled by researchers.

– Jennifer Tomase