Roads less taken

A glimpse into three unusual Summer School courses

The career of a literary scholar often takes strange and unexpected turns. Starting out in a conventional, well-defined field, a scholar may suddenly veer off into new territory, guided by a compelling insight or the realization that some relatively neglected body of work is ripe for academic exploration.

Several scholars at Harvard Summer School are currently taking their students on such a voyage of discovery. We talked to three of them about how their interests evolved and what excites them about these unexpected byways.

‘Poetry that doesn’t die.’

Listen to Richard Thomas discuss the work of Bob Dylan and you soon realize Thomas is more than a fan. He’s a Dylan scholar.

He knows and can quote from Dylan’s complete oeuvre, from the Woody Guthrie-inspired protest songs of the early ’60s to the latest Dylan CD. He knows the discography, including outtakes and bootleg tapes. He has read all the biographies, memoirs, and critical studies and can speculate with insight on how Dylan’s life and art interrelate.

You might expect this level of expertise from someone who is offering a course on Dylan at Harvard’s Summer School. What you might not expect is for that same person also to teach courses on Cicero, Ovid, and Virgil.

Thomas, a professor of Greek and Latin in the Department of the Classics, has been a Dylan admirer since his days as an undergraduate at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. For years his enthusiasm for Dylan existed separately from his academic interests, but over time the two drew closer together.

“It’s interesting how I evolved from being a fan to realizing that this could be an intellectual and academic topic, even though Dylan himself has always been somewhat contemptuous of people who try to analyze his work.”

In his course Thomas interrogates Dylan’s output with the full array of analytical tools commonly employed in literary scholarship. The seminar explores Dylan’s creation of personae, the tension between his restless experimentation and the expectations of his audience, his use of intertextuality and the cultivation of a personal mythology, the peaks and valleys of his artistic career, and his appearances in film.

Thomas makes no apologies for Dylan’s status as a popular entertainer. In fact, he points out, the distinction between high and low culture is of rather recent origin. It did not exist for Virgil, who, according to his early biographers, was often besieged by screaming fans. Thomas sees Dylan as a modern Virgil, both for his popularity and for the power of his verse.

Thomas, who delivered a paper on Dylan and the Greco-Roman literary tradition last year at a conference on Dylan at the University of Caen, France, firmly believes that Dylan’s work will endure long beyond its own historical moment.

“It’s poetry that doesn’t die because human nature doesn’t change, and art that captures human nature in the most powerful way keeps on living.”

Strangers in the dark

Another scholar who questions the boundaries between popular entertainment and “serious” art is William Flesch, who teaches “The Noir Antihero in American Fiction and Film.” The course explores novels by Dashiel Hammett, Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, Philip K. Dick, and Chuck Palahniuk, as well as film adaptations based on their books.

Flesch, who also teaches such topics as Renaissance literature, contemporary poetry, and literary theory at Brandeis University, admits to being an enthusiastic fan of noir fiction and movies.

“I totally love them. I think they’re just wonderful.”

But his enthusiasm for the genre does not get in the way of his critical perceptions.

“I’m interested in the question of why we become engrossed in fiction, why we become anxious about characters even though we know they’re fictional. The noir genre is a very good place to think about this.”

Flesch believes that studying a tightly plotted novel like Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon” can shed light on these narrative issues, as can the excellent 1941 film adaptation directed by John Huston and starring Humphrey Bogart.

One of the things Flesch talks about is the way the noir genre, which emphasizes the anonymous nature of city life, is reflected in the experience of moviegoing itself, in which an auditorium is full of strangers sitting in the dark, watching images on a screen. He also emphasizes the differences between the film experience in noir’s heyday – the 1930s and ’40s – and today’s world of multiplexes and DVDs.

“We talk about how noirs are constructed for an age of continuous showing where many people came in in the middle of the movie and stayed to watch the part they’d missed. It’s strange that a mystery should be constructed that way, but if you watch a movie like ‘The Maltese Falcon’ you realize it’s true.”

‘Continuing tradition of black discourse’

The writers of the Harlem Renaissance have for many years been accorded a significant place in American literary and cultural history. Authors like Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, and Zora Neale Hurston are widely taught and anthologized. What is unusual about the Summer School course on the Harlem Renaissance is not the subject matter but the background of the professor.

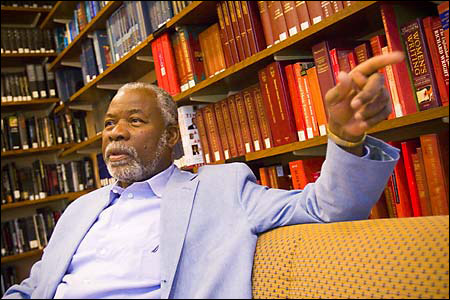

F. Abiola Irele is a visiting professor of African and African American Studies and of Romance Languages and Literatures. Born in Nigeria and educated in London and Paris, his fields of interest are the literature of Francophone Africa and the African diaspora. In viewing the work of the Harlem Renaissance writers he takes a global perspective.

“I see the Harlem Renaissance as a major phase of the continuing tradition of black discourse going back to Olaudah Equiano and Phillis Wheatley in the 18th century, and also the traditional response in folk forms such as spirituals. The Harlem Renaissance was a gathering of all that into a climax.”

According to Irele, the Harlem Renaissance writers have also had a great impact on later movements throughout the world, including the Haitian Renaissance and the Negritude movement of French-speaking African and Caribbean writers.

W.E.B. DuBois, a seminal figure in the Harlem Renaissance as well as one of the founders of the NAACP, not only had an impact on the American Civil Rights movement, but also on the freedom movement in South Africa. Irele points out that Nelson Mandela acknowledges a debt to DuBois in his autobiography.

Irele, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the Caribbean writer and politician Aimé Césaire, has been aware of these influences since his student days at the University of Paris.

“The writers of the Negritude movement were fully aware of the literature of the Harlem Renaissance. In fact, from the 1930s to the 1960s, all blacks in Paris were familiar with these writers.”