A diarist in the Class of 1858

Undergrad’s journal mixes daily joys, history-making sorrows

Wednesday June 16th

– Alice and I went down and bought 6 red handkerchiefs for the race.

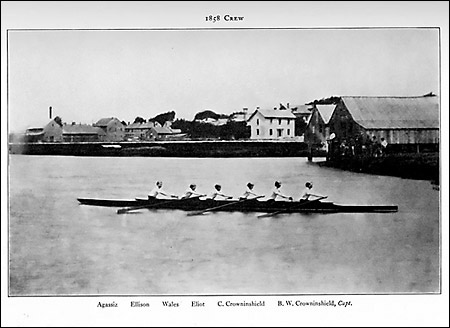

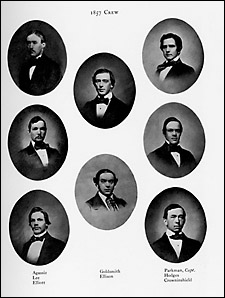

Who would have thought the purchase of six Chinese silk handkerchiefs would change Harvard’s athletic history? Benjamin W. Crowninshield, Class of 1858, kept a journal through his junior and senior years at Harvard and it demonstrates two diverse truths about life – that “the more things change, the more they stay the same” and “you never know what’s going to happen next.” Crowninshield had brushes with history that he never anticipated.

Crowninshield, captain of the rowing team, and his sister, Alice, purchased the handkerchiefs to be worn as head bandanas. Also involved with choosing the brightly colored scarves was Charles W. Eliot, Class of 1853, a future president of Harvard. The bright colors would ensure that family and friends would recognize their team as they rowed by. In fact, the handkerchiefs were actually crimson and the beginning of Harvard’s school color. It might not have been the first time bandanas were used on the teams, but crimson ultimately became the official color of Harvard. (Briefly after the Civil War, the color magenta was so popular that crimson fabric was hard to find, so magenta served as Harvard’s color for a few years.) In this particular race, the Harvard team was challenging the “Fort Hill Boys,” a Boston Irish rowing club.

In 1858, future-president Eliot was an instructor, not a student, but was enlisted to complete the crew. Eliot, showing almost a surfeit of school spirit if not an excess of ethnic sensitivity, wrote to his fiancée, Ellen Peabody, about the race. “Hurra! Hurra!! Hurra!!! We’ve beaten the entire crowd tremendously – and made the quickest time ever made round the course … Ellen It was perfectly splendid … The boys say that Eliot was excited and I know I felt mighty pleasant, not an idea of being tired … What an ovation we had – the paddies behaved beautifully – shook hands and owned up handsomely – Everybody seemed in a state of ecstasy.” Crowninshield recorded on June 19 that the Harvard team defeated the Boston men by “1m. 58 seconds.”

Undergrad’s journal mixes daily joys, history-making sorrows

Helen HannonSpecial to the Harvard News Office

Wednesday June 16th

– Alice and I went down and bought 6 red handkerchiefs for the race.

Who would have thought the purchase of six Chinese silk handkerchiefs would change Harvard’s athletic history? Benjamin W. Crowninshield, Class of 1858, kept a journal through his junior and senior years at Harvard and it demonstrates two diverse truths about life – that “the more things change, the more they stay the same” and “you never know what’s going to happen next.” Crowninshield had brushes with history that he never anticipated.

Crowninshield, captain of the rowing team, and his sister, Alice, purchased the handkerchiefs to be worn as head bandanas. Also involved with choosing the brightly colored scarves was Charles W. Eliot, Class of 1853, a future president of Harvard. The bright colors would ensure that family and friends would recognize their team as they rowed by. In fact, the handkerchiefs were actually crimson and the beginning of Harvard’s school color. It might not have been the first time bandanas were used on the teams, but crimson ultimately became the official color of Harvard. (Briefly after the Civil War, the color magenta was so popular that crimson fabric was hard to find, so magenta served as Harvard’s color for a few years.) In this particular race, the Harvard team was challenging the “Fort Hill Boys,” a Boston Irish rowing club.

In 1858, future-president Eliot was an instructor, not a student, but was enlisted to complete the crew. Eliot, showing almost a surfeit of school spirit if not an excess of ethnic sensitivity, wrote to his fiancée, Ellen Peabody, about the race. “Hurra! Hurra!! Hurra!!! We’ve beaten the entire crowd tremendously – and made the quickest time ever made round the course … Ellen It was perfectly splendid … The boys say that Eliot was excited and I know I felt mighty pleasant, not an idea of being tired … What an ovation we had – the paddies behaved beautifully – shook hands and owned up handsomely – Everybody seemed in a state of ecstasy.” Crowninshield recorded on June 19 that the Harvard team defeated the Boston men by “1m. 58 seconds.”

His diaries suggest that Crowninshield handled his Harvard classes easily – with the exception of “that cursed nonsense” Logic. He was athletic – in addition to rowing, he never missed an opportunity for skating or running, and he often walked between Boston and Cambridge. And he had school spirit – on Thursday, March 18th, 1858, he wrote, The piano came out, and at 6 ? we had a meeting of the Glee Club. I was chosen President, Learoyd Director, and Abercrombie Treasurer. He was also a member of the Porcellian Club and Pierian Sodality, was treasurer of the Hasty Pudding, sang with the choir, and played the cello.

In 1856, he lived in Hollis Hall, No. 9. He often visited his friends, but could also spend a whole day making a model boat. In addition to school activities, he took drawing courses, music lessons, went to dances, theaters, concerts and spent many evenings in Boston at Parker’s Restaurant and playing billiards at Ripley’s. He seemed to have almost a compulsive zeal for his many activities.

He also had a penchant for making friends. Crowninshield noted a conversation with a young Robert Gould Shaw: Wednesday, November 19th, 1856, … [W]e went around to visit Mr. Shaw a Freshman who proposes to become a member [of the Pierian Sodality]. Sat there about a half hour talking to him. He seemed rather inquisitive for a Freshman but perhaps it was his very greenness made him so. Though it doesn’t seem as though Crowninshield immediately warmed to Shaw, they became good friends. This green freshman was the same Robert Gould Shaw who would soon serve as colonel of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. The Fifty-Fourth was the first African-American regiment trained as regular army soldiers. (The movie “Glory” is based on the story of Shaw and his regiment.)

The same day that Crowninshield spoke with Shaw he played whist “till the sociable [a party] ([W.H.F.] Lee’s) was ready at L. Erving’s room.”

William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee was also a good friend of Crowninshield’s. Lee would not finish his tenure at Harvard. Both young men were athletic and loved to socialize: Wednesday, June 24th, 1857, Went in town to a supper at Parker’s given in honor of [W.H.F.] Lee, [B.D.M.] Jones, [F.L.] Lowndes all of whom are going to leave the class – The eatables were excellent – I took too much of the drinkables and consequently on Thursday June 25th – I was too sick to get up till 2 o’ clk.

The Civil War changed everything. Crowninshield enlisted and began as a lieutenant in the First Massachusetts Cavalry on Nov. 5, 1861; he then became first lieutenant on Dec. 19, 1861; captain on March 26, 1862; then major on Aug. 10, 1864. He saw action at South Mountain, Antietam, The Wilderness, Hawe’s Shop, Petersburg, Weldon Railroad, Deep Bottom, Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek. He served as aide de camp to Gen. Philip Sheridan, then became provost-marshal, Middle Militia Division. He remained with Sheridan till mustered out Nov. 6, 1864. Crowninshield reached his highest rank of brevet colonel, U.S. Volunteers, on June 17, 1865.

Rooney Lee’s father, it turne out, was leader of the Confederate forces, Gen. Robert E. Lee. Rooney Lee reached the rank of major general in the Confederate army, but was captured in 1864. As a prisoner, he was automatically placed under the direct control of the provost marshal. In a curious twist of fate, Benjamin Crowninshield was then provost marshal on Gen. Sheridan’s staff. Francis Crowninshield, Benjamin’s son, later wrote that it was “a truly embarrassing position for both of them.” When he was under arrest, Rooney Lee preferred not to accept “any of the privileges Crowninshield tried to bestow upon him.” Happily, they did reconcile after the war.

These young men and many others were on the same Harvard campus and in the same clubs, little knowing that in a few years they would be fighting furiously on opposite sides in the Civil War. If they met in battle they would have killed each other. Lee and Crowninshield survived the war; Shaw would die at Fort Wagner in South Carolina on July 18, 1863.

After the war, Crowninshield married and moved to New York and entered the dry-goods commission business. The family came back to Boston in 1869 and he worked for Wheelwright, Anderson & Co., dry-goods commission merchants He retired in 1879. In 1891, he wrote the “History of the First Massachusetts Cavalry.” His health began to fail around this time. He traveled to Europe in 1891 for a rest and died in Rome in 1892. His diary was published in 1941 by his son, Francis B. Crowninshield, under the title, “A Private Journal, 1856-1858.”

Friday, June 25th, 1858

Our Class Day!! Went to breakfast at 7 1/2 – Went down to the square & purchased $00 [sic] worth of all round collars & some ribbon & fans. Busy giving orders &c till ? of ten when I marshalled [sic] the class and we marched down to University where Dunning delivered the prayer and Tobey a good class chronicler – We then marched to the President’s house – not a breath of air and the thermometer 90 [degrees] in shade – I saturated my shirt &c instanter – There we ice creamed &c, and at 11 ? all marched with the faculty and guests to the Unitarian Church – Here all hot – yes roasted, and dripping with perspiration we listened to the oration by Henry Adams and the Poem by Noble – Both were good, the latter splendid – After singing the ode, we all adjourned to the spreads in the college buildings – My family came round to my room a little while – when they went over to our (9 of us) spread in Hollis – I & Cabot stayed and changed our faded clothes – We partook of some wine that father sent me out from Boston – I looked in on our spread and loafed round – not much loaf, but rather too much business in it – making my orders go well – At 3 we had the dance on the green – A good simon pure, real, dance an hour or two long – The wind came out East and it was tolerably cool – Danced in the Hall ? of an hour & then we marched round & cheered the buildings & finished by singing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ &c and getting the flowers round the tree – After entirely demolishing my own & most everybody’s else hat I came round to my room, and indulged in a very necessary bath – after which and a new suit of clothes I went round to the Lowell’s & the President’s house – The yard was brilliantly and beautifully illuminated with lanterns of various different colours – Walked round &c & finally came home & treated Wheelock & Messrs Fries & Zohler to wine – I was pretty well played out when I turned in –

– The author thanks Edward Burdekin, Timothy Driscoll, Michelle Gatchette, Barbara Meloni, David Mittell ’39, and Theresa Muxie.