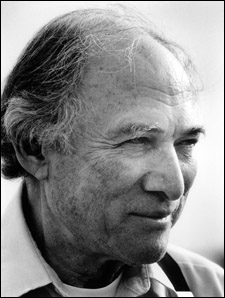

Sheldon Harold White

Faculty of Arts and Sciences – Memorial Minute

At a Meeting of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences November 22, 2005, the following Minute was placed upon the records.

Sheldon Harold White, John Lindsley Professor of Psychology, Emeritus, was born on November 30, 1928 in Brooklyn, N.Y. He graduated from Harvard College in 1951 and earned an M.A. at Boston University in 1952. The following two years were spent as a research assistant at the Army Medical Service Graduate School. White earned his Ph.D. degree from the University of Iowa in 1957. For the next eight years he served as a faculty member in the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago. In 1965, White returned to the Graduate School of Education at Harvard, serving as Associate Professor and later Roy E. Larsen Professor of Education and Cognitive Psychology. He moved to the Department of Psychology in 1973, served as Chair of the Department of Psychology from 1984 to 1987, and was appointed John Lindsley Professor of Psychology in 1994. He retired in 2001.

Shep White (he was always referred to as “Shep” by his family, friends, and colleagues) made major contributions to his field in many ways. He was an acknowledged expert in the field of child development and education. One of the most frequently cited of his papers integrated the extensive literature on the dramatic changes that occur in children between the ages of five and seven years, known to students as the “five to seven shift.” His approach was marked by his conviction that research findings from the laboratory should be applied to the actual day-to-day practice of teaching. In his own career he demonstrated that it was possible for the same person to move from the laboratory to the classroom, and to the committee chambers of government and to perform outstandingly in each of these arenas.

His many publications include works on the history of ideas and practices in child development, analyses of ethical issues that arise in the course of educational practice and, most particularly, on matters of educational policy. All of these were placed in the larger context of social changes in values in the United States and Europe. As his work progressed, the emphasis evolved from a major focus on such components of the learning process as attention, intelligence, practice and the like, to a concern for the many other factors that influence learning in the real world. Basic to these was the recognition that social and emotional influences during the course of development also help or hinder learning.

In pursuing these questions White was alert to the problems of measuring change. Questions of how the effects of educational programs should be assessed was critical in judgments of their success or failure. It was in this context that in 1993 he accepted an appointment as Chair of the Board of Children and Youth and Families of the National Research Council, one of five appointments to National Research Council boards. He served on many professional, state and local committees devoted to problems of child learning. The core theme of most of these appointments was the application of research findings to educational practices, and the question of producing a valid method for assessment of programs that had been implemented. Perhaps the best known such national program was Head Start. White served as a member of the advisory panel project to design the assessment of Head Start program, and later as Chair of the Advisory Panel on implementing the design in actual practice. All in all, White served in a senior advisory capacity to various Head Start panels from 1989 to 1997. White’s influence in the conduct of Head Start programs was significant, and the fulfillment of his long expressed hope for the building of bridges from the laboratory to the school. At different times he served in an editorial capacity to seven leading national journals. Among White’s numerous contributions was his service as consultant to the Children’s Television Workshop in the development of the well-known “Sesame Street” program.

In all of his capacities White was an impressive and admired teacher. The model that he provided was as a thoughtful scientist who cared about the social consequences of the real-world application of his findings, not only in terms of their effectiveness but also their consonance with basic ethical principles. Shep was many things – a man of honesty, integrity, and compassion, of warmth and humor and of great courage. He had a wise tolerance for harmless foolishness in others, a wry smile for human foibles, his own and those of colleagues. Students knew that they would get an understanding listener, wise practical help in their troubles and warm encouragement as they strove to complete their education. He would go to lengths to help them dig themselves out of bureaucratic pits that they had created themselves. For White, no students were ever “lost” and would never be abandoned if still trying to make progress in their studies.

He was rarely visibly angry, but when he was, it was always because some injustice or unfairness had been inflicted by someone with power on somebody with less power, or when some action was being urged that might place the requirement of honesty and fairness below that of self-interest. As a colleague, White was remarkable for his steadfast good humor, warmth, and sensitivity to the feelings of others. His office door was always open to those who were looking for guidance, or a stimulating discussion of some problem of current interest. He was a good man who valued integrity above popularity, and in so doing achieved both.

Shep and his family spent many happy times in their lakeside summer home in New Hampshire. His wife Barbara Notkin White, two sons and daughters-in-law, Andrew S. and Elizabeth White, Gregory S. and Amie White, grandchildren Olivia, Alexander and Jonathan White, and a brother, Aaron White, survive him.

Respectfully submitted,

Jerome Kagan

Philip J. Stone

Brendan A. Maher, Chair