Sophomore retraces routes of illegal immigrants

De Beausset experiences some of the trials of those traveling to U.S.

It was late and dark and dangerous in the Mexican city of Altar.

The bus let Kyle de Beausset off at 3 a.m. seemingly in the middle of nowhere, leaving the Harvard sophomore groggily wondering what to do and where to go.

Lugging all his belongings in a large backpack, de Beausset said later that things began to go wrong almost from the start. The other passengers to get off the bus grabbed the only cab at the stop. Once they left, de Beausset was alone in the dark on a deserted street.

So when the green van pulled up and offered him a ride to a hotel, de Beausset accepted despite his misgivings.

Understanding migrants’ plight

De Beausset had gotten to Altar the hard way. After Hurricane Stan slammed into his native Guatemala in October, de Beausset felt compelled to take the rest of the year off from his Harvard studies and return home. He had become interested in the plight of illegal immigrants and their dangerous journey to the United States, so he decided that before he returned to his studies the following fall, he would explore their world.

At his family farm in Guatemala, de Beausset decided to trace the steps of illegal immigrants from Guatemala to the United States, walking in their shoes whenever possible, to experience what they experience.

De Beausset started by contacting a coyote in Guatemala – a person who specializes in smuggling immigrants across the border. The coyote, after initially agreeing to de Beausset’s plan, backed out, saying that his contacts along the migration route would be suspicious, which could damage the coyote’s reputation and his ability to do business.

De Beausset decided to press on anyway and trace the route on his own. Along the way, he relied on the advice and moral support of a group of Harvard students interested in immigration issues. Led by Harvard junior Raquel Alvarenga, who chairs the Latino Immigration Policy Group at the Institute of Politics, the group established an online blog, called Immigration Orange, where de Beausset posted accounts of his journey.

On March 12, he crossed from Guatemala legally into Mexico at the border town of Tapachula. After staying the night there, he went south to the Mexican border town of Ciudad Hidalgo, opposite the Guatemalan town of Tecun Uman.

Also in this issue:

Immigration issues are bound to U.S. values

It was there that de Beausset’s education about life as an illegal migrant began. He persuaded a taxi driver to bring him to the spot where goods and people were illegally ferried across the river separating the two countries.

For just 10 pesos, he was easily taken from Mexico into Guatemala. He saw military and police on both sides of the border observing the traffic back and forth, doing nothing to stop it. He returned to Mexico the same way, but was harassed by Mexican border guards until he showed them his passport.

From there, de Beausset traveled to San Cristobal de las Casas and then to Arriaga in Northern Chiapas.

In Arriaga he was conducted to houses where illegal migrants were staying. De Beausset stayed there for several days, talking with the migrants and listening to their heartbreaking stories.

Arriaga is a common stopover for illegal migrants on the route north, de Beausset learned, because they can hop trains heading out of town to make the journey quicker. De Beausset met dozens of people from all over Central America who were traveling on their own, on foot, and on the cheap. Many had left family behind and had no one in the United States to help them get started.

The migrants had similar tales to tell. Crime and beatings on the road were common. Many had lost all their money and most of their belongings.

“I saw the migrant population that suffers,” de Beausset said. “For them, being mugged or suffering gang violence is a fact of life.”

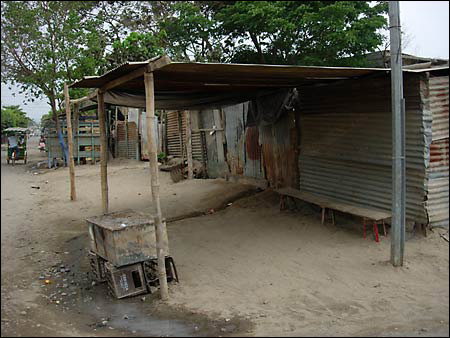

After Arriaga, de Beausset decided to head north. He traveled to Mexico City and then further north to Altar, a transit point near the U.S. border for those heading to Sasabe, a jumping-off point for the desert crossing into the United States.

The green van

After the bus let him off in Altar, de Beausset was at a loss. Not knowing what else to do, he accepted the late-night ride. But once he got inside the green minivan, he knew he’d made a mistake.

There was a man sleeping on the seat behind him, which not only made him uncomfortable, but convinced him the vehicle wasn’t a regular taxi, as the driver claimed.

The driver seemed a bit jittery, his speech unfocused, which made de Beausset wonder if he were completely sober. The man quizzed de Beausset about why he was in Altar and de Beausset told him he was investigating illegal immigration. Shortly after de Beausset got in, the van turned onto a dirt road, prompting de Beausset to ask where they were taking him.

The driver said he was going to a guest house and asked a few more uncomfortable questions about how much money he had and whether he had a camera. The driver asked de Beausset whether he wanted a coyote to get him across the border. De Beausset dodged the questions as well as he could, insisting he wouldn’t pay a coyote. He was eventually let off at a guest house where he was led to a room crowded with 20 other people, most likely migrants, who slept on carpeted bunks three rows high.

De Beausset had just enough time to think about his predicament, when the driver returned with a different car and a second man, promising to take him to a regular hotel. Still suspicious, but also still at a loss about what else to do, de Beausset got in the car.

They passed two hotels that the driver waved off as full and headed away from town into the dark. In response to de Beausset’s queries, the driver twice pointed to lights in the distance as their destination, but drove past each: one a gas station, the second a lone light on a telephone pole.

They eventually pulled into a dark parking lot deep in the desert where, after much whispering between his “guides,” one of them demanded money and threatened de Beausset with an unseen gun. Realizing he was at their mercy, de Beausset handed over some cash and then grabbed his backpack and rolled out the door of the slow-moving car.

The car sped off, leaving de Beausset a three-hour walk back to town, during which he nervously eyed the headlights each time a car approached.

That experience led de Beausset to abandon his plans for his final stop at Sasabe, and he headed to a friend’s house in Phoenix instead. He arrived in early April, roughly three weeks after he set out.

De Beausset has been back in Cambridge for several weeks and has spoken at several forums on immigration reform. De Beausset said in a recent interview that he realizes that things in Altar could have gone much worse, but said he learned about the experience of illegal migrants in a way he couldn’t have gotten from books.

“The biggest thing [I accomplished] was just quantifying the personal suffering that they experience,” de Beausset said. “Here you work abstractly, you talk about ideas. … The most important thing is to broaden our understanding, realize what’s happening, and keep in mind the suffering.”