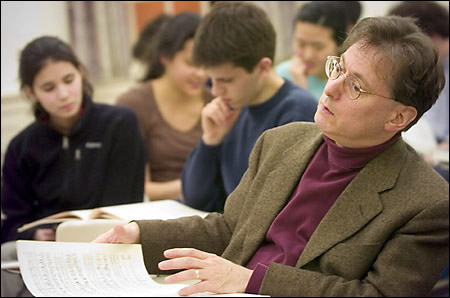

Robert Levin celebrates Mozart’s birthday

Passion in motion

Sitting in a swivel chair in his basement office, Robert Levin can barely keep his agile pianist’s fingers off the telephone. He has just learned that his friend Yehudi Wyner won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for musical composition with his piano concerto “Chiavi in Mano,” and he wants to be the first to call the composer in Italy and give him the news.

What makes the moment especially exciting is that Levin commissioned the concerto and premiered it in February 2005 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Levin, the Dwight P. Robinson Jr. Professor of Music and one of the world’s most admired pianists, has commissioned pieces from many of today’s composers and sees that activity as an essential part of his multifaceted musical career.

“Without that, I wouldn’t feel right about plunging into the 18th century. To make the message of the past relevant and indispensable, we must be thoroughly anchored in today.”

Levin’s use of the word “plunging” to describe his engagement with the music of the past is no hyperbole. Levin does what few other contemporary musicians dare to do – play Mozart cadenzas that are truly improvised, made up on the spot as the orchestra sits silent and the audience listens in rapt attention.

Music 180 with Professor Levin:

It is the way Mozart intended his cadenzas to be played, the way he himself played them, but it is a skill that has fallen into disuse. In today’s concert halls it is far more common to hear cadenzas that have been previously composed, then played note for note.

Levin’s facility with the musical language of Mozart has been earned through intense study and scholarship. Since he wrote his senior honors thesis at Harvard on Mozart’s unfinished works, he has been on a quest to understand the master’s compositional methods, to fathom the music’s inner structure as well as the social, cultural, and political milieu from which it sprang. But to master Mozart’s idiom well enough to play and improvise in his style, one must take risks.

“If you’re going to be a performer, there comes a time when you put your tails on and you go out on stage and do dangerous things – breathtaking, scary things, and this is how you celebrate being alive.”

Hearing Levin discuss the compositional techniques of Mozart, Bach, or Beethoven, one cannot doubt that he appreciates the genius of these artists, but at the same time he has no patience for those who would treat the music of the past as though it were holy writ, a familiar, comforting set of musical scriptures to be approached with care and deference.

“If all you care about is whether music is being played correctly, you might as well watch someone putting up Sheetrock. The familiar is not what Beethoven had in mind. He wanted to thrill and amaze us.”

One genre that Levin finds admirably brimming with musical risk taking is jazz, especially of the swing era. He speaks with astonishment of three-minute jazz recordings from the 1920s and ’30s on which musicians like Louis Armstrong and Lester Young play 20-second solos that are “incandescent with imagination and daring.”

For Levin, these great jazz improvisers had a great deal in common with the composers of the classical era who might have delighted a bewigged drawing room crowd just as Charlie Parker thrilled audiences at Birdland. The similarity becomes clear, Levin explains, when you read Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s treatise on improvisation, where he advises the musician to start with a bass line, build chords on top of that, and finally add an improvised melody.

“And you know what it sounds like when you do that? It sounds like Coleman Hawkins playing ‘Body and Soul.’”

As much as he admires jazz, Levin has no illusions about his own ability to play the music. It is an idiom he hasn’t fully absorbed in the way he has absorbed classical music. Perhaps Levin’s strengths as a musician stem from the clarity with which he sees his own limitations. As a young man he studied composition with Leon Kirchner and Nadia Boulanger and wrote a series of original compositions. Then he met composer John Harbison, a 1987 Pulitzer Prize winner, but at the time an unknown junior fellow at Harvard’s Society of Fellows.

“I decided he had something I didn’t have.”

But instead of sulking, Levin devoted himself to performing Harbison’s music.

“I realized it was more important for me to play the music of someone like Harbison than to slave over music of my own that may never be played.”

Today, he urges young performers to seek out and perform the musica of unknown, contemporary composers. He tells them that playing the work of these composers is like betting on a horse, just as 40 years ago he bet on Harbison.

“And you see, I tell them, my horse came in.”

In honor of Mozart’s 250th birthday, the Harvard University Choir will perform ‘Mozart’s Requiem’ – the composer’s final (and incomplete) composition, using the completion by Robert Levin. The performance, accompanied by the Orchestra of Emmanuel Music, is Sunday (April 23) at 8 p.m. in the Memorial Church. Tickets are $10 general; $5 students/senior citizens, available at the Harvard Box Office (617) 496-2222.