A tour of human history, with guide Jared Diamond

Pulitzer-winning author delivers Prather Lectures

Some time around 1680, an Easter Islander cut down the island’s last tree, dooming any hopes of an environmental recovery on the remote Pacific Ocean speck and condemning his descendants to poverty, civil war, and cannibalism.

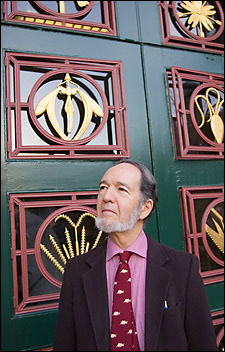

The environmental and social disaster on one of the world’s most remote spots has parallels to our globalized world today, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Professor Jared Diamond said in a March 8 talk. It was the second of a series of three Prather Lectures in Biology delivered by Diamond last week.

With modern technology and rapidly increasing rates of consumption, humans are destroying the environment on a global scale and the Earth can be viewed as today’s Easter Island. Like the Easter Islanders, surrounded by thousands of miles of ocean and having cut down the last tree out of which they could have made a boat, we’re stuck on planet Earth. If it goes bad, so do we.

But Diamond said we have an advantage that the Easter Islanders didn’t. We’re the first people who have global communications and modern scientific investigations. We, more than any people in history, have the chance to learn from others’ mistakes – both those made today and those made in the past.

“There are obvious lessons to be learned from the past,” Diamond said. “The biggest lesson is to take environmental problems seriously.”

Diamond, a UCLA geography professor and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, drew hundreds of Harvard students, faculty, and staff to last week’s talks, filling lecture halls and overflowing overflow rooms. The Prather Lectures were sponsored by the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and the Science Center Lecture Series.

Diamond, whose 1997 book “Guns, Germs, and Steel” is in its 183rd week on the New York Times bestseller list, presented his broad theories about why human history unfolds as a story of certain people conquering all competitors, and about why some societies collapsed dramatically while others adapted and succeeded.

In his third lecture, delivered Friday evening in the Biological Laboratories, Diamond presented his current research into how nations cope with crises by reappraising core values – or refusing to reappraise core values.

Diamond joked about the breadth of his subject at the start of his first lecture, delivered before at least 800 watching live or in overflow rooms in all four Science Center lecture halls. Diamond said he planned to cover about 130 centuries on five inhabited continents, leaving about four seconds to cover each century on each continent.

“So I’ll have to skip some details,” he said.

Despite the need for generalizations, Diamond offered explanations about the rise of European dominance of the peoples of other continents in ways that racist explanations of the past left wanting.

Diamond attributed the domination of European societies largely to geographical and biological happenstance. At the end of the last ice age, 13,000 years ago, all humans were living in small bands, surviving through a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The area of the Fertile Crescent, where farming first arose, was the native home of several of today’s most important food crops and domesticated animals.

Other parts of the world were populated with animals that proved impossible to domesticate or were of limited usefulness once they were. With an advantageous mix of domesticated plants and animals, Europeans benefited from an agricultural lifestyle that allowed populations to grow and that provided surplus food for inventors and bureaucrats.

The close proximity to animals allowed animal diseases to cross into humans, forcing those human populations to develop resistance. Native people without the same resistance fell to the germs brought by Europeans, just as surely as if they had been shot or conquered by the sword.

On the subject of societal collapse, which he covered in his second lecture, Diamond offered examples of both successful and failed societies. Among the failed societies were the Easter Islanders, a Norse settlement in Greenland, and the Maya. In each of these cases, societies failed to adapt to changing circumstances, whether in the local environment, the broader climate, or relationships with nearby friends or enemies.

By contrast, Diamond offered the example of Japan after being unified under the shogun. That society responded to deforestation by regulating the cutting of trees, beginning scientific tree plantations, and becoming self-sufficient in wood products. Another successful example is the Icelandic Norse, who prosper today in a fragile environment centuries after their Norse brethren on Greenland died. In each of those successful cases, society adapted to challenges and survived.

In his last talk, Diamond said that despite Vice President Dick Cheney’s assertion that “The American way of life is non-negotiable,” events of today are challenging three core American assumptions: that it’s OK to have high levels of natural resource consumption, that we can ignore many of the world’s problems as if we lived in a gated community, and that the rights of the individual trump the rights of society.

Diamond said many nations have reappraised core values and successfully emerged. Recently in the United States, the values that allowed racism and segregation to exist have been successfully challenged, Diamond pointed out.

The negotiations over the American way of life remain to be held, Diamond said, but they can’t occur between Americans and the people of other nations.

“It remains to be seen if we Americans are willing to negotiate with ourselves,” Diamond said.