Wunderkinder study wonders

Freshmen-turned-scholars curate Houghton ‘Book of Hours’ exhibition

The faculty member behind the seminar is Jeffrey F. Hamburger, professor of the history of art and architecture, who wanted to expose the freshmen to primary source materials at Houghton Library early in their academic careers. “The rare book library is as much their library as is Lamont Library or Widener,” said Hamburger. “They should take advantage of it.”

They did, spending countless hours in Houghton Library, Harvard’s primary repository for rare books and manuscripts, studying illuminated manuscripts firsthand – learning both how to handle the fragile texts and how to read them.

Hamburger didn’t make it easy for them. Each student had to choose a book of hours – a type of handmade medieval prayer book – to analyze and study for a final project. “I deliberately chose manuscripts that were less well known because I didn’t want students, even freshmen, to be able to fall back on a large body of previous publications,” explained Hamburger.

“There’s really no more direct way of coming into contact with the past than, with all proper care and precautions, to take a book or any ancient artifact in your hands and puzzle it out and to see just how intractable they are,” said Hamburger. “It’s very, very different from seeing one reproduced in a textbook, where it’s ostensibly explained and given a label.”

The original research produced by the students, and the manuscripts they used, became the basis for an exhibition in Houghton Library called “The Book of Hours.” The initial suggestion and encouragement for the exhibit came from William Stoneman, the Florence Fearrington Librarian at Houghton, who helped make the rare texts available to the students.

The book of hours

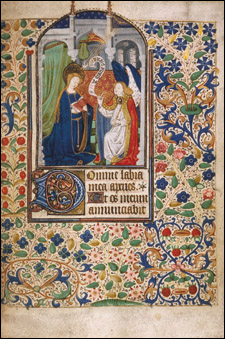

Books of hours are medieval prayer books that predate printing technology and fall into the category of illuminated manuscripts, which are usually intricately wrought with hand-lettering and artistic imagery. Many took years to create. “It’s often said that books of hours are the proverbial bestsellers of the late Middle Ages,” explained Hamburger. “And indeed, if anyone in the late Middle Ages was likely to own a single book then – at least if you lived in France, the Netherlands, or England – the book of hours was most likely to be the one.”

Medieval books of hours vary widely in size, content, decoration, and illumination. They tended to belong to the well-to-do, and artists and scribes customized each to suit its owner’s desires and level of piety. The eye-catching images are not always what one might expect to adorn prayers. For instance, a page might have a solemn religious image in the center, and a picture of a snail, dragon, or monkey cavorting in the margin of the same page.

“The Middle Ages were in some ways far less reverent and decorous than we imagine,” explained Hamburger. “Very often in medieval manuscripts, one finds grotesque, playful imagery in the margins.”

Ultimately the course, primarily a class in medieval art history, was also a course in the history of reading, the history of prayer, the history of religion, and study of the cultural context in which these books were used. All of which only increased the challenge presented the students, to write a 10- to 12-page analytical paper, beginning with the full technical description of the manuscript.

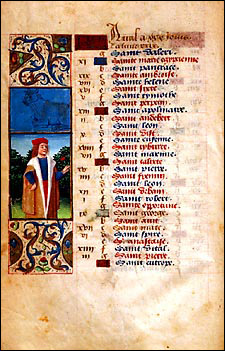

Students prepared their full-length essays and also a “distilled” version, a much shorter summary piece for the exhibition catalog. Nicole Bass ’09 contributed the first catalog summary on “Marking Time,” analyzing the meaning of the illustrations, both religious and secular, in a French book of hours.

‘The Book of Hours: Picturing Prayer in the Middle Ages’ is on exhibit through March 11 in the Houghton Library. Hours: Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, 9 a.m.-5 p.m.; Tuesday, 9 a.m.-8 p.m.; Saturday, 9 a.m.-1 p.m. For details, call (617) 495-2411.

Kate Patrick ’09 also studied a French book of hours, and wrote the entry “Shades of Meaning,” which discusses the symbolism behind grisaille – images painted entirely in gray.

Jane Cheng ’09 composed “Manuscripts for the Market,” analyzing a book of hours produced in the early 16th century when illuminated manuscripts were in their later days. “I talked about the way that the illuminations were done late in the flourishing of books of hours,” said Cheng. “You can tell a lot of things about the ways that they tried to speed up production – something that was not in the end good for illuminations, and not feasible for art, especially when printing came along.”

Cheng, who works in Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center, also helped pull together the exhibition: She designed the catalog, contributed three of the four appendices (including a technical description and a description of medieval binding), and built the cradles which hold the manuscripts in the display case.

A fourth student, Julia Renaud ’09, took on the challenge of working with fragment from a mid-15th century book of hours. After a great deal of digging, she used saints’ names in the fragment to trace it to a region in west central France.

A conversion experience

“Obviously books like this have to be protected,” said Hamburger. “And that’s why they’re kept here at the Houghton. On the other hand, it’s very, very important that we allow our students to come into contact with these books. By that I mean not only to see them, but to turn the pages and to experience them for what they are.”

Hamburger, who plans to add the course to his regular rotation of classes, beginning this summer, hopes the course had a significant impact on his first-year students. “I’m convinced that it will have been, you might say, a conversion experience for them. That’s in a sense what you hope for – whether someone’s going to go on or not, whether they discover something entirely new and find a lasting enthusiasm. That’s really what you live for as a teacher.”