The transformations of an itinerant mind

Scholar is interested in times of transition, old and new

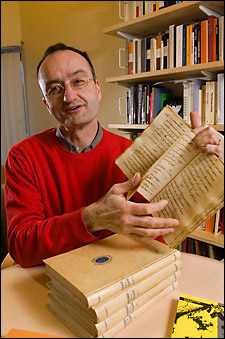

Looking at the courses Francesco Erspamer is teaching his first year at Harvard, one is struck by their historical breadth. There is a course on the great figures of the Italian Renaissance, one on the writers of the “decadent” period at the turn of the 20th century, and two that examine the Italy of today, its politics, culture, fiction, and cinema.

One might wonder whether anything unites these disparate periods, what if anything could Michelangelo Buonarotti possibly have in common with Michelangelo Antonioni? For Erspamer, however, there is a very clear underlying theme, and that theme is change.

“The Renaissance has always fascinated me, as I am fascinated by the modern period. I like periods with a sense of transformation and change.”

Hired in 2005 as professor of Romance languages and literatures, Erspamer has managed to encompass a considerable amount of transformation and change in his own life. Raised in Parma, Italy, the son of a professor of medicine, Erspamer was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps, but after three years of medical school, he realized that the profession of medicine did not suit his interests.

“I discovered that I was more interested in theorizing than in accepting facts at face value.”

Erspamer switched to the study of modern philology, focusing on the Italian Renaissance, a period that artists and scholars of the time saw as a rebirth of classical knowledge, but which today’s historians view as the beginning of the modern era. He found the field a welcome change from the hard science point of view that was the basis of medicine.

“In medicine everything is solid facts, experiments, proofs. In cultural studies, there is no solid ground. It is all relational, comparative.”

Erspamer’s doctoral dissertation, which became his first published book – “La biblioteca di don Ferrante: Duello e onore nella cultura del Cinquecento” (1982), an exploration of 16th century codes of honor and the etiquette of the duel – was inspired by his grandfather, a veteran of the Italian army who had served as a second in several affairs of honor in the early 20th century. Anxious to acquit himself in the proper manner, he had purchased several books on dueling, which years later he passed on to his grandson.

Erspamer was fascinated by the elaborate customs that surrounded dueling. He was struck by the fact that the communication that took place between the rivals and their supporters, the orchestrated series of actions that led up to the event, seemed to overshadow the duel itself. In fact, according to Erspamer’s research, a relatively small number of duels were actually fought. The majority were settled during the talking stage.

He compares these affairs to the high profile trials of today, which are also governed by elaborate rules and procedures and which hold such fascination for the public. This need to regulate human behavior through highly specified codes and regulations he sees as characteristic of the modern era.

“It is typical of modern society that people substitute talking about actions for the actions themselves,” he said.

In 1984, Erspamer joined the comparative literature faculty of Seconda Università di Roma. The appointment coincided with another change in his approach to scholarship.

“I began to feel that there was too much interpretation in the world. I was always an avid reader and a collector of books, and at a certain point it overwhelms you – what are all these people doing? Where does it all lead?”

Erspamer’s answer was to concentrate on editing and translating existing works. Among these were the letters of Pietro Aretino, a poet and satirist who employed the arts of flattery and blackmail to eke out a living among the wealthy and powerful of 16th century Italy; Iacopo Sannazaro’s “Arcadia,” a pastoral love story much imitated by later Renaissance writers; writings by Lorenzino de’ Medici and the poet Celio Magno; and an Italian translation of the autobiography of American frontiersman Kit Carson.

Erspamer moved to the United States in 1993 to take a position in the department of Italian studies at New York University. Initially skeptical about the level of scholarship he would find in this country, he soon realized that studying one’s own culture from an outside point of view held important advantages.

“When you build your identity based on your own cultural views, you end up being mentally conservative. Studying culture from a distance is much more stimulating because it allows you to see with greater depth.”

Moving to a new country altered Erspamer’s scholarly perspective yet again. With several major editorial projects behind him, he felt ready to give interpretation another try, only this time his scope would be far broader. His new work, “The Creation of the Past: On the Time of Culture,” completed but not yet published, is currently being translated into English. Erspamer plans to publish it in the United States. In it, he argues that the past needs to be knocked off its pedestal.

“I have nothing against the past. I don’t think the past exists, of course. It’s just one type of present.”

For Erspamer, the past is always in contention. What happened, what it means, is always subject to reevaluation and is often manipulated to suit the purposes of those in power or seeking power. The problem comes when the past is seen as sacred and untouchable and when this sacred past is held up as a pattern for present behavior.

“There is a tendency to sanctify tradition because we can find no reason to preserve it. But I believe that the desire to make tradition absolute is a sign of weakness.”

Erspamer recognizes that certain absolutes are necessary, laws that safeguard life and property, for example, or laws governing common communication systems such as language. And as the father of three children he admits that when it comes to child rearing it is not always expedient to open every injunction to critical questioning. But in the struggle between faith and reason, Erspamer comes down firmly on the side of reason.

“The Enlightenment introduced the idea of criticism, which means to evaluate, to judge, to choose. In fact, we are always choosing, and this is the opposite of the idea of the sacred – the sacred is not choosable. Having faith is the same as not being able to choose.”