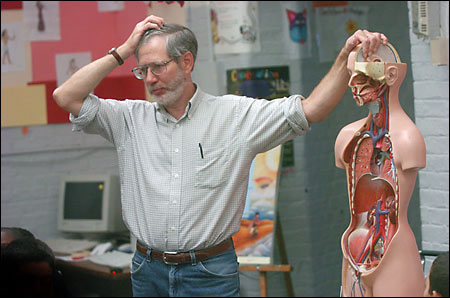

Katler’s anatomy

HSPH brings science to inner-city schools

Marshall Katler’s torso is a necessary burden, even if he drops it on the way to the elevator and has to drag it hurriedly along Huntington Avenue. He doesn’t complain, though. He quickly makes his way to the Farragut School in Roxbury, where 24 fifth-graders await Katler’s – and his torso’s – arrival.

Katler, a research specialist at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), is bringing his model torso and head to teach these students about science, particularly how the environment can affect one’s health.

Since 1986, the HSPH’s Environmental Health Education Program (EHEP) has been partnering with Boston’s inner-city schools, including the Farragut, to bring science and health education into classrooms to supplement the schools’ programs.

In the beginning, one-time classes and health fairs were offered, but a variety of components have been added over the years, such as yearlong programs, before-school and after-school science clubs, and teacher workshops. The Farragut is the first school to institute a yearlong program, so Katler, who is the founding director of EHEP, will be visiting for one hour, every other week, for the entire academic year. “I like teaching kids about environmental issues.”

Today the students are being given a pre-test to assess their knowledge of the subject and then an overview of the human body. The torso is essential to Katler’s presentation. It has removable organs that he detaches and passes around the classroom of teacher Thomas Kelton, who is hosting Katler in his classroom for the second year.

The students shout out the names of the organs taken from the model torso and head and get a brief – for now – explanation of them. When Katler gets to the brain, he uses the opportunity not only to tell them that the soft and squishy organ allows them to do just about everything they do, but to advise them that wearing a bike helmet will help prevent the brain from being seriously injured in an accident.

One by one, students pass along the familiar – and not-so-familiar – organs with their little hands. The bladder provokes some laughter and loud “eeuw” sounds when its function is discussed. Even a part of the body not featured on the torso model is brought up by one boy who asks, “Where’s your Adam’s apple?” in response to Katler asking, “Any more questions about the body?” It is evident that the young audience’s interest is piqued.

Katler says that his EHEP students receive a more in-depth understanding of public health and science through this program than they would otherwise. He explains that his students “might learn about soil and about rocks” in their regular school science programs, “but they don’t necessarily learn about soil pollution and how it can affect them.” Katler adds, “they might learn the properties of water and evaporation and condensation and rain and so forth ä but they don’t necessarily know about mercury or lead or even bacteria that get in the water and can hurt their bodies.”

Because Katler will be visiting Kelton’s classroom regularly, he will be able to spend at least several weeks on the topics of air, water, noise, and land pollution, to ensure that the students digest what he’s teaching. Classes include demonstrations, experiments, take-home projects, and field trips.

Through his emphasis on how things can go wrong, Katler ensures that his students learn the basics of physiology. For example, when the students are introduced to air pollution, they learn about respiration – how the respiratory system works and why we need oxygen. They take home petri dishes that they open for a certain amount of time, mold spores fall down onto the dishes and grow, and then they bring the mold and fungus back to class. Katler then brings in his HSPH mold and fungus experts, who examine and test the specimens and the students see the results.

“I think the kids are learning very good science. They’re learning how to think, how to work together, how to analyze things. The teachers really like it because they’re learning too. They learn the information and then they can teach it the following year,” says Katler.

This particular program is geared for fifth graders. They will need to learn the science information for the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) test. Kelton, who has been teaching at the Farragut for the past six years, says that the program prepares his students for the exam, which translates into improved test scores.

Kelton also credits the partnership for an increased overall interest in science. “The students are more attentive in their other science classes,” he says.

But, more importantly, the lessons learned travel with the kids out of the classroom and into the community. “When we talk about pollution, they use this information – they go home and become advocates at home,” says Kelton.