Juggling in Afghanistan

Divinity School student finds laughter is the best medicine in Kabul

While Divinity School student Zachary Warren drives his unicycle, what is driving him? A love of laughter, says the juggler, trick cyclist, and entertainer known as the “Jolly Juggler.” In fact, last summer Warren’s love of laughter drove him all the way to Afghanistan.

Hooking up with a buddy (and fellow juggler) who was home from his job in Afghanistan this past Christmas, Warren was surprised and delighted when the friend told him, “You’ve got to check this out – there’s a circus down the street from us in Afghanistan!” Warren contacted the circus and was impressed enough with what he found to travel to Afghanistan in the summer of 2005.

In Kabul, Warren found the Afghan Mobile Mini Circus compound to be a center of laughter. Each day, between 50 and 350 refugee children would find their way to the compound to learn circus tricks, to create acts for the circus, or to participate in the other services offered by the circus, which included classes in journalism, calligraphy, painting, and tae kwon do. “There is music every day, there is always music, spontaneous dancing, singing, and the spirit of play,” said Warren.

The circus compound was designed for refugee youths living in Kabul to escape and heal from what might be an otherwise grave existence. In rebuilding Afghanistan, “the focus hasn’t been on children and children’s development,” said Warren. “Most of the talk is on ‘How do we get the parliament in order, how do we create security for foreign investors, and how do we fix the health care system?’ All of these are necessary and important things, but the step beyond that is for foreign communities to focus on the younger generations.”

According to Warren, many Afghani refugee parents are too busy trying to survive in this nation devastated by decades of strife that they don’t have time to attend to their children’s psychosocial needs. “One of children’s basic needs after war is to learn to trust again,” said Warren. And the circus give them something to trust in – adults who care and friends with whom to play.

The Afghan Mobile Mini Circus

Warren was struck by the difference between those children who came to the circus and those who didn’t: “I noticed that many Afghan kids don’t smile or laugh much. It’s a rare child who does. But the kids involved with the circus laugh and smile all the time. Emotionally, they seem far more developed than kids outside the circus.”

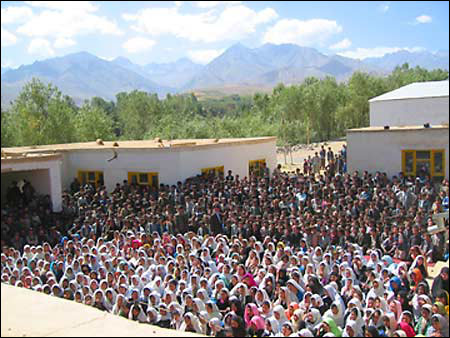

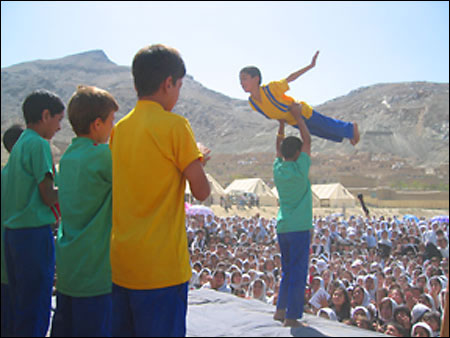

At the circus, Warren taught juggling and unicycling, mostly to children between the ages of 4 and 14. Together, they would develop acts that the children would eventually execute at performances. The Afghan Mobile Mini Circus comprises three circuses: two junior, or children’s, circuses and an adult circus. The adult circus travels throughout Afghanistan, while the children’s circuses perform in and around Kabul.

Warren reported that the circuses would perform primarily at schools. For ten days he traveled with the adult circus. The clowns, acrobats, and jugglers would tumble into a town, find the local school, and ask if they could set up a performance. “Every time, the school would just say, ‘Wow, we’d love that!’ They’d cancel all classes, drop everything, and gather together to watch the circus. They’d never seen anything like this before,” said Warren.

There is no long-standing tradition of circuses in Afghanistan. The Afghan Mobile Mini Circus was founded by a Danish-Iranian citizen in 2001. It has since grown to comprise 11 full-time Afghani members/teachers and numerous volunteers.

In addition to juggling, unicycling, stilt walking, and clowning around, the circus performance features acts that convey important messages – in fun ways. A dysentery prevention piece features a giant dirty hand that chases a clown around the stage. Eventually, the clown gets sick and whines and complains to the audience’s delight. Finally, a giant clean hand appears and heals the clown. Other acts convey messages of malaria prevention, land mine awareness, and conflict resolution. Religion is also used as a medium for these messages. The Afghan artists use selections from the Qur’an during performances to emphasize Muslim values of education for girls and boys, as well as of hygiene, peace, and pluralism.

Laughter as therapy

Warren believes that laughter and the circus heal people, both mentally and physically. “Laughter bonds people, and it also provides a sort of emotional catharsis. Feelings of anger, tension, and fear can be released and neutralized through laughter. We know that humor is an effective coping mechanism and survival mechanism,” he said. “Laughter has been shown to improve cognitive control and to lower blood pressure and shorten recovery time among stroke patients. Among both kids and adults, it nurtures a tolerance for novelty, ambiguity, and change, creative problem solving, and risk-taking.”

And laughter was the treasured result of the circus: “Time and again,” said Warren, “I would go to the performances and I would ask them [the audience], ‘What part of the performance did you like?’ Invariably, they’d say, ‘We love to see our children laugh, we haven’t seen that in so long.’”

Warren recalls with emotion the case of one of his unicycling students whose father died in August. When the circus teachers learned of the father’s death, “we all thought he should be home with his family, but he came back the next day and he kept coming back … people would tell him to go home but he refused and kept insisting that he wanted to perform. He was doing what he needed to be doing: being in a supportive community where play could be a way of coping with the realities of life.”

While in Afghanistan, Warren began collecting data for his research project on the healing properties of play and laughter. He videotaped children playing on seesaws, both within the circus compound and away from the circus. His hypothesis is that children, surrounded by the creativity and playfulness of the circus, will smile and laugh more on the seesaw than will children unfamiliar with the circus. He filmed more than 700 minutes of children playing, and his next step is to code the laughter and smiles.

World’s records

Back home in Cambridge, Warren hasn’t forgotten the circus – neither his own performances, nor those of his colleagues in Kabul. He’s engaged in record-breaking circus-like activities for the benefit of the Afghan Mobile Mini Circus. On Nov. 20, Warren set a new world’s record for the “fastest marathon while juggling three objects.” He completed the 26.2 miles with a time of 3:07:05 at the Philadelphia Marathon. “I figured that juggling to a world record would be an appropriate way of raising awareness and funds for the circus,” said Warren, who fundraises through the Web site http://www.Unicycle4Kids.org/.

Next, Warren plans to set two new world’s records: one for the most number of miles in one hour on a unicycle, and the other for the fastest time for unicycling 100 miles. He will make the attempts at the Dover International Speedway in Dover, Del., a 1-mile NASCAR racetrack, next May. He had planned to make the latter world record attempt last October, but found himself too weak after his summer in Afghanistan. Security precautions had kept him from training by jogging or unicycling through the streets of Kabul – “a foreigner on a unicycle is called a ‘moving target,’” joked Warren – and his diet of Afghani local fare, primarily naan, rice, and an oil/potato soup called kachalu “wasn’t exactly the breakfast of champions,” he said.

Warren hopes to return to Kabul next summer. He sees the restoration of play and laughter, as accomplished by the Afghan Mobile Mini Circus, as important steps in the development of a modern Afghanistan: “If you want to rebuild a country,” he said, “what moves people beyond survival mode, what makes people proactive and creative, what gives them hope for the future and the skills and the imagination to create a better future – that’s what the circus does.”