Enter to grow in wisdom

A tour of Harvard’s gates

(Flash 7 required: click to download)

From the perspective of Harvard’s 369-year history, the gates in and around the campus are a relatively new phenomenon. For more than two-thirds of its existence, Harvard had nothing more to guard its perimeter than a low post-and-beam fence. When the Johnston Gate – the initial component of the present-day enclosure – went up in 1889, many decried its towering piers and elaborate ironwork as a pretentious imposition on the school’s austere Puritan heritage. But as time went on and succeeding Harvard classes raised generous sums to extend the fence and punctuate it with stately apertures, the structure grew to be as familiar and beloved as any of the school’s more venerable monuments.

If anything, the gates have become such fixtures in the Harvard landscape that they verge on invisibility. To hurried, preoccupied pedestrians, their details and decorations fade and blur, their inscriptions go unread. They are reduced to mere function, a passageway from the Yard to the street, from the street to the Yard. Of course, that is essentially what a gate is. But the Harvard gates are more than that. Each has its own story to tell – some simple and straightforward, others complex and ambiguous, some embodying the notions and values of another age, others enshrining the ideals and aspirations of today.

This Web page is dedicated to telling some of those stories, in the hope of enriching the experience of all those who walk through these portals, whether for the first time or the thousandth.

Johnston Gate

When it was completed in 1889, Johnston Gate stood alone. The other gates and even the brick and iron fence that now encloses the Yard were still in the future. And while nothing quite as grand as its delicate ironwork and massive brick and sandstone piers had ever graced the spot before, the location of the gate has served as the Yard’s main entrance since the end of the 17th century.

The gate is named for Samuel Johnston, Class of 1855, who left Harvard $10,000 for its construction. A resident of Chicago, Johnston is described in his 1886 obituary as a bachelor and a “well-known capitalist,” and by a fellow member of the Chicago Club as “a short, ruddy faced bon-vivant.” A book of reminiscences by one of Johnston’s neighbors describes him drinking a toast on the front steps of his house as the Chicago fire blazed nearby.

Designed by the Boston architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White, Johnston Gate was the first example at Harvard of Colonial Revival, a style that, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries became almost standard for Harvard buildings. Built of salvaged bricks chosen for their varied texture and color, the structure also helped to popularize what has come to be known in the building trade as “Harvard water-struck brick,” used on most Harvard buildings since that time.

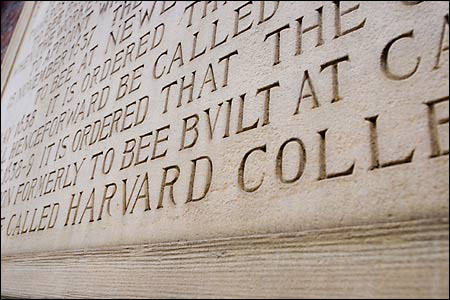

The gate bears two plaques inscribed with the earliest records of Harvard’s founding, an inscription from “New England’s First Fruits” (1643) and the records of the General Court of Massachusetts Bay establishing the College.

1874 Gate and 1886 Gate

Completed in 1900, the 1874 Gate was closed in 1926 after the building of Lionel Hall, the freshman dorm that now blocks the entrance. The 1886 Gate, finished in 1901, was also closed in 1926 after Mower Hall was constructed.

1870 Gate

The 1870 Gate stands between the two dormitories, Lionel and Mower, facing the back of Appleton Chapel. Between the chapel and the gate is a sundial, and around its vase-shaped stone base are inscribed the words “On this moment hangs eternity.” However, since most of the Roman numerals on the sundial’s face have worn away, precisely which moment eternity is hanging on is now hard to determine.

The 1870 Gate’s ironwork was in unusually bad shape when the restoration of the Harvard Yard fence was undertaken in the early 1990s. Now that it has been repaired and repainted, conservationists predict that along with the rest of the fence it will last another 100 years. Nevertheless, because it does not lead directly into the main part of the Yard, it is usually kept padlocked.

1881 Gate

The 1881 Gate, erected in 1905, serves as the principal entrance to Phillips Brooks House, which houses the Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA), coordinating nearly 80 student-run public service programs. The building was named for Phillips Brooks (1835-1893), a renowned preacher, minister of Trinity Church in Boston, and author of the hymn “O Little Town of Bethlehem” – hence the cross that surmounts the gate’s ironwork structure and the New Testament quotation (“Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make ye free,” John 8:32).

It is one of the few gates not designed by Charles F. McKim. The designer was Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow Jr., nephew of the poet and a member of the architectural firm Longfellow, Alden & Harlow. Longfellow also designed Bertram and Eliot Halls in the Quadrangle and the third-floor library of Fay House in Radcliffe Yard. Stylistically, the gate is entirely in keeping with McKim’s Colonial Revival designs.

1876 Gate (Holworthy)

The 1876 Gate, aka Holworthy, is located just to the northwest of Holworthy Hall, a freshman dorm. Both gate and hall were named for Sir Matthew Holworthy, an English merchant, whose bequest of £1,000 in 1678 was the largest single gift to Harvard in the 17th century. The gate is on an axis with the 1857 Gate, leading pedestrians through the Yard, across Pusey Plaza to the Science Center, and beyond.

An inscription above the gate leaves no doubt when it was dedicated: “Given by the Class of 1876 on Commencement Day 1901.” The opposite side of the shield bears the inscription “In memory of dear old times.” The quotation is from “The Ballad of the Bouillabaisse” by William Makepeace Thackeray, in which the poet returns to a Parisian inn to sample the famous Mediterranean fish stew (accompanied by a bottle of good burgundy) that sustained him and his fellows in their youth:

I drink it as the Fates ordain it.

Come; fill it and have done with rhymes;

Fill up the lonely glass and drain it

In memory of dear old times.

1879 (Meyer Gate)

The Meyer Gate, erected in 1901, is named for George von Lengerke Meyer, Class of 1879, who paid for its construction. Born in Boston in 1858, Meyer held positions in state and local government while also managing his business affairs. He later served as ambassador to Italy and Russia and was appointed postmaster general in 1907 by Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1909, President Taft named him secretary of the Navy, a post he held until 1913. He is credited with making the Navy more efficient and with proving the feasibility of carrier-based aviation. Under his jurisdiction, pilot Eugene Ely successfully took off and landed from temporary platforms erected over the decks of Navy cruisers. Meyer died in 1919.

A massive brick structure with deep side wings, the gate comprises a wide center opening for carriages and two arched foot gates. It was designed by Charles F. McKim, who was Meyer’s brother-in-law. Matching stone plaques grace the tall brick piers. The one on the right bears a veritas shield. On the left is a carving, partly weathered, of a pelican feeding her young. According to legend, the female pelican in times of famine would peck at her own breast and feed her young with her blood. The bird thus came to represent self-sacrifice and was considered a symbol for Christ.

An inscription surrounding the carving gives Meyer’s name and records in Latin, the fact that he was a Bostonian and a member of the Class of 1879. In addition, there is a phrase in German, “Furchtlos und Treu” (fearless and true), which is also the motto of the kingdom of Württemburg as well as the title of a German marching tune.

1997 (Bradstreet Gate)

Harvard’s newest gate honors the first published poet of the American Colonies, Anne Dudley Bradstreet (1612-1672). Arriving as a young newlywed in Salem harbor in 1630, Bradstreet found time to write poetry while leading the hard and demanding life of a Puritan pioneer. Her collection of poems, “The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America” appeared in London in 1650 and was a great success.

Bradstreet lived in what is now Harvard Square, and her home is believed to have stood on the spot now occupied by Citizen’s Bank. Her associations with Harvard College were many. Her father, Thomas Dudley, was governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and one of the original Harvard overseers. Her husband, Simon Bradstreet, also became governor of Massachusetts Bay and was an overseer of Harvard College. Among their children were Samuel, Class of 1653, and Simon, Class of 1660.

The Bradstreet Gate and adjoining fence replaced a section of chain-link fence that had stood since the construction of Canaday Hall in 1974. Designed by architect Michael S. Teller, the gate was installed in 1995 as part of a multiyear effort to restore and complete the brick and ironwork fence enclosing Harvard Yard. It was dedicated on Oct. 4, 1997, to commemorate the 25th anniversary of women living in Yard dormitories. A plaque is inscribed with a quotation from Bradstreet: “I came into this Country, where I found a new World and new manners at which my heart rose.”

1887 Gate and 1888 Gate

The grand semicircular sweep of the double 1887 and 1888 gates, separated by a stone lion’s head spouting water into a granite basin, comes as something of a surprise to pedestrians traveling the curving brick walkway that connects Pusey Plaza with Quincy Street. The gate seems too imposing for its location. The railing that protects walkers from tumbling to the busy street below ensures that one cannot get far enough away from the structure to appreciate its scope, and the view from either gate is blocked by the back of Canaday, the Yard’s newest dorm.

The explanation lies in the fact that when the gates were erected in 1906, the appearance of the Yard and environs was considerably different. In place of Canaday, built in 1974, stood the more compact Hunt Hall, the original Fogg Museum. The gate on the right led past this building toward the transept entrance of the Memorial Church, while the left hand gate led directly to Sever Hall. And in those pre-underpass days, Broadway, a quiet street populated mostly by horse-drawn vehicles and an occasional trolley, was still on a level with the Yard.

1908 (Robinson Gate)

The Robinson Gate is one of two gates given by the Class of 1908, the other being the larger, more impressive Eliot Gate. The Robinson Gate leads to a basement entrance of Robinson Hall, a building that was constructed in 1904 to house the School of Architecture and is now home to the History Department. Built in 1936, the Robinson Gate was designed by Richmond Knapp Fletcher (1885-1965), Class of 1908. A portrait painter as well as an architect, Fletcher also composed several fight songs still in the repertoire of the Harvard Band, among them “Yo-Ho! (the good ship Harvard)” and “Gridiron King.”

1885 Gate

The 1885 Gate, erected in 1904, faces west toward the rear entrance of Sever Hall and east toward the main entrance of the Fogg Museum, straddling the axis that connects the two buildings. Designed by Charles F. McKim, the gate features a pair of carved stone urns with ram heads atop its two brick piers.

1936 (Emerson Gate)

Another gate designed by the multitalented Richmond Knapp Fletcher ’08. A simple foot gate erected in 1936, it provides access to Emerson Hall, which houses the Philosophy Department.

1908 (Eliot Gate)

Grandest of the four gates designed by R.K. Fletcher, the Eliot Gate commemorates Charles William Eliot (1834-1926), president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, the longest presidency in the University’s history. Given by the Class of 1908, this vehicle gate was designed to provide a driveway entrance to 17 Quincy St., which served as the president’s house until 1971. This was the year that the new president, Derek Bok, seeking greater privacy for his family, decided to move his residence to Elmwood, the former residence of poet James Russell Lowell. Bok thus became the first Harvard president to live outside Harvard Yard. The house that he abandoned is now the headquarters of the Office of the Governing Boards, and its dining hall is still used for formal occasions.

The gate’s brick piers bear two plaques. The one on the left reads, “In memory of Charles William Eliot, 1834-1926, given by the Class of 1908.” The one on the right is inscribed with a quotation from a biography of Eliot: “He opened paths for our children’s feet to follow. Something of him will be a part of us forever.”

1936 (17 Quincy Gate)

The gate leading to the main entrance of 17 Quincy St. is another gift of the Class of 1908 and was designed by R.K. Fletcher, a member of that class. Erected in 1936, it is a small foot gate whose simple ironwork arch, low enough for a tall person to reach up and touch, conveys an impression of intimacy that fits well with the modest leafy brick path lined with perennial borders.

17 Quincy Drive Gate

This gate is easy to miss, since the drive to which it once provided an entrance no longer exists. In its place is a lawn whose center of interest is a large bronze sculpture by British artist Henry Moore. The gate is permanently closed.

1915 Dudley Gate

Don’t look for the Dudley Gate. It was demolished some time around 1947 to make way for Lamont Library. And while not on the same scale as other vanished architectural wonders like the Colossus of Rhodes or Pennsylvania Station, it nevertheless continues to exert a certain fascination for students of Harvardiana.

Erected in 1915 for the then-magnificent sum of $25,000, the Dudley Gate was given by Caroline Phelps Stokes, who bequeathed the money to her nephew Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, Class of 1891, with the understanding that he would use the funds to build a monument to her ancestor Thomas Dudley (1576-1653), governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Stokes, an architect of the firm Howells & Stokes, designed an impressive brick and limestone structure that included a clock tower more than 30 feet high with a full-length bas-relief of Dudley on one side and a long inscription on the other detailing the governor’s history and accomplishments. The inscription is the only part of the structure that remains. It has been incorporated into the Dudley Garden, a leafy retreat between the south side of Lamont and the section of tall brick fence fronting Massachusetts Avenue.

Lamont Gate

The Lamont Gate was designed by Henry Richardson Shepley ’10 of Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch & Abbott. It provides access to Lamont Library from Quincy Street and was erected between 1947 and 1949, coinciding with the building of Lamont. A relatively simple gate, it faces the larger, more elaborate Hallowell Gate across Quincy Street. The Hallowell Gate is the entranceway to the Barker Center, formerly the Freshman Union.

Lamont Delivery Gate

A wrought-iron gate across the rear delivery entrance of Lamont Library.

1880 (Bacon Gate)

The 1880 Gate used to be called the Stone Gate, and indeed it is the only gate constructed almost entirely of white limestone. It looks into the Dudley Garden, although the view is partially blocked by a brick wall, on the other side of which is the lengthy inscription salvaged from the Dudley Gate. No can one enter the garden through the gate because it is nearly always locked. Access to the garden is through a gate inside the Yard.

Erected in 1902 and designed by Charles F. McKim, the gate was paid for principally by Robert Bacon, Class of 1880. Bacon (1860-1919), whose name is engraved on a limestone panel to the left of the gate, was born in Jamaica Plain, Mass., and was a partner with the banking firm J.P. Morgan and Co. He served as United States secretary of state in 1909 and as ambassador to France, 1909-1912.

1890 (Dexter Gate)

Erected in 1901 and designed by Charles F. McKim, the 1890 Gate was a gift of Mrs. Wirt Dexter in memory of her son Samuel Dexter, Class of 1890, who died in 1894. The gate leads into one of the arched passageways that cut through Wigglesworth.

Two inscriptions by Harvard President Charles William Eliot adorn the gate itself: on the outside, “Enter to grow in wisdom”; on the inside, “Depart to serve better thy country and thy kind.”

1877 (Morgan Gate)

Designed by Charles F. McKim, the gate was a gift from Edwin D. Morgan, Class of 1877. A relative by marriage of the financier J.P. Morgan, Edwin was immensely wealthy in his own right. He shared J.P. Morgan’s enthusiasm for ocean racing, serving as commodore of the New York Yacht Club from 1893 to 1894.

In partnership with the renowned yacht designer Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, Morgan competed successfully in a number of important sailing races including the America’s Cup. Described by one writer as a man who would think “no more of buying a yacht than the average man does of picking up a paper as he passes a newsstand,” Morgan owned some 17 vessels including steamers, schooners, sloops, America’s Cup Defenders, and many smaller yachts.

1889 Gate

Similar in style to the Dexter Gate, with piers composed of alternating layers of brick and limestone, giving it a vaguely Moorish air, the 1889 Gate provides access to another arched passageway through Wigglesworth. It was designed by Charles F. McKim and dedicated at Commencement 1901.

Porcellian Gate (McKean Gate)

Look up at the keystone of the tall, arched Porcellian Gate and you will see a limestone carving of a boar’s head (there’s one on the other side, too). Why this porcine portrait? For an explanation, look across the street at 1324 Massachusetts Ave. The unassuming brick building, whose ground floor houses the clothing shop J. August, is the headquarters of the Porcellian Club, the oldest and most exclusive “final” club at Harvard (note the boar’s head in profile over the doorway). Final in this sense means once you’re in, you can’t join another one, and membership is for life.

Only members are allowed inside the club, and the perpetually drawn shades ensure that outsiders can’t even sneak a peek at the interior (which is reputed to have changed very little in the club’s 200-plus years). The only exceptions to this rule were Winston Churchill and Dwight Eisenhower, but this honor was on a one-time-only basis; when Ike asked if he could come back a second time he was refused. The list of Porcellian members includes architect H.H. Richardson, Civil War hero Robert Gould Shaw (leader of the black 54th Regiment), Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, President Theodore Roosevelt (his younger cousin FDR was rejected), and writer George Plimpton.

The Porcellian began when an undergraduate named Joseph McKean, Class of 1794, served a group of friends a dinner of roast pig. The original name, the Pig Club, was soon changed to the more genteel, latinate Porcellian. The gate is also known as the McKean Gate in honor of the club’s founder, who later served (1808-1818) as the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory.

The Porcellian Club donated the money to build the gate, which was completed in 1901.

1857 Gate

The Class of 1857 Gate, completed in 1901, is the only gate in Harvard Yard with three archways, all of them designed exclusively for pedestrian use. Two elegant wrought-iron lanterns flank the center opening.

On the left side of the gate is a tablet commemorating the two houses located on the edge of Cowyard Row that housed Harvard College in its first years of existence. These were the Peyntree House, occupied by Harvard’s less than successful first master Nathaniel Eaton, and the Goffe House, which served as a dormitory. Their foundations were discovered when Massachusetts Avenue was torn up in 1910 to build the Red Line.

Two tablets above the gate’s outer archways bear a Latin inscription from one of Horace’s Odes. The translation reads, “Thrice happy and more are they whom an unbroken band unites, and whom no sundering of love by wretched quarrels shall separate before life’s dying day.”

1875 Gate

Surmounted by a veritas shield, the 1875 Gate bears on its entablature a quotation from Isaiah (26:2): “Open ye the gates that the righteous nation which keepeth the truth may enter in.” Its designer, Charles F. McKim of the Boston architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, may have had in mind a symbolic union of the two great sources of Western civilization – Hebrew and Greek – when he chose to combine the words of the prophet with an emphatically classical style of architecture.

Two Doric columns frame the gate. As a student at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, McKim would have had a thorough grounding in the history and meaning of the architectural orders and would have known that the plain, sturdy Doric is considered masculine in style and appropriate to structures with military connotations. In 1900, when the gate was built, Harvard was still an intensely male place, and perhaps McKim envisioned the gate as an invitation to young men to take on the rigorous intellectual, moral, and physical training that would prepare them to soldier on through the vicissitudes of life.

Another interesting thing about the 1875 Gate is that when Strauss Hall was built in 1926, the gate was moved 50 feet to the south.