Yard yields wisdom in pipe stems

(Gold mine of information excavated by students)

It looks like the stuff any gardener might find while turning over a new tomato bed: rusty nails, chunks of old brick, shards of glass, maybe a sprinkler head or two. But to the students of Anthropology 1130: “The Archaeology of Harvard Yard,” it is a potential gold mine of information. Stored in plastic bags, each representing a 1-meter-square grid coordinate, these dirt-caked fragments will together help tell the tale of what life at Harvard was like in the 1600s, and may uncover important information about the little-recalled Harvard Indian College, founded in 1655 to help the University fulfill its mission to educate “the English and Indian youth of the country in knowledge and godliness.”

– Video: Digging in the Yard (2:36)

“We can’t always predict what we’ll find in a dig,” says William L. Fash, director of the Peabody Museum and a professor of Central American and Mexican archaeology in the Anthropology Department. “The other day we found a soda can. Very exciting,” he joked.

Still, though the official groundbreaking at the two Harvard Yard sites – one beside Massachusetts Hall and the other in front of Matthews Hall – was just a few weeks ago and only the first foot or so of ground has been excavated, students have already uncovered some pieces that date back a century or more. “I’ve never taken anthropology courses before,” says Indira Phukan ’09, “so this is my first excavation. It’s very, very cool. I’ve been excavating over by Massachusetts Hall and we’ve come up with … a lot of pottery and ceramics, and a lot of pipe stems.”

“They’ve found lots of glass goblets, and even a glass pipe stem, which is very unusual,” Fash says. “But what’s really valuable for us are the clay pipes, because you can date them closely by the bore of the stem, and the pottery, because the particular styles can be closely dated also.”

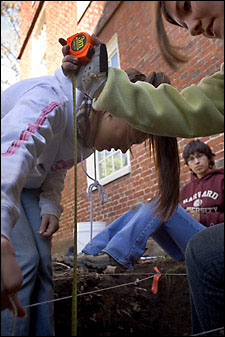

Hip-deep in her work, Diana Loren (left) talks to students about their excavation project in the Old Yard. Though the excavation is being supervised by William L. Fash, it is being conducted by Peabody associate curators Loren and Patricia A. Capone because both have specialized in historical archaeology – that is, in cases where documentary evidence complements the remains – of the northeastern United States. Right, Erin Frey ’08 (from left), Indira Phukan ’09, and Nicole Ledoux ’07 take measurements of the pit.

Hip-deep in her work, Diana Loren (left) talks to students about their excavation project in the Old Yard. Though the excavation is being supervised by William L. Fash, it is being conducted by Peabody associate curators Loren and Patricia A. Capone because both have specialized in historical archaeology – that is, in cases where documentary evidence complements the remains – of the northeastern United States. Right, Erin Frey ’08 (from left), Indira Phukan ’09, and Nicole Ledoux ’07 take measurements of the pit.

The student archaeologists expect to begin finding material from the 1600s at the 4-to-5-foot level, and hope to go as deep as 6 to 7 feet. Students must screen the ground as it is removed, because most of the articles will be in pieces – not only because they were considered refuse at the time, but also because of the weight of decades of soil bearing down on them. For now, every scrap the students unearth is being kept – including plastic twist-ties and aluminum pop-tops – because when it comes time to catalog their finds, even debris of more recent origin helps them put their discoveries in context.

Helen Human ’06 has her hopes about the excavation, “I think it would be really neat to find remnants of the Indian College, some material that you can identify that was used by the students.”

“One of the questions we have about the Indian College is, Were the Indians fully acculturated, or did they maintain some of their own culture?” says Fash. “Sometimes a very tiny object can speak volumes about issues such as trade, religion, social status, or lifestyle.”

The Indian College, founded to teach native Wampanoag and Nipmuc students English and Protestantism, was the first brick building erected in Harvard Yard. The two-story structure survived until 1695, when it was dismantled to make way for newer construction, but the Indian College itself did not have such good luck. After just a few years, says Fash, “the wind had shifted. The vast majority of the Native Americans here had succumbed to smallpox.”

Of the eight students known to have been housed and educated in the Indian College building, only one, Caleb Cheeshahteamuck, graduated, in 1665. “We can’t go and ask Caleb what it was like to be the first graduate of the Harvard Indian College,” Fash said at the October ceremony, where the dig was also given the blessing of the ancestors through the entreaties of Chief F. Ryan Malonson of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah. “So we have to keep in mind we’re opening a very small window” into his experiences and those of his fellow students.

Though the excavation is being supervised by Fash, it is being conducted by Peabody associate curators Patricia A. Capone and Diana Loren, because both have specialized in historical archaeology – that is, in cases where documentary evidence complements the remains – of the northeastern United States. It is hoped the course will continue for some years, expanding excavations at the site near Matthews Hall.

“Archaeologists like to believe they’re the only ones who can really get at the truth,” Fash continued at the groundbreaking. “I don’t trust or believe everything I read. We do have some accounts of the Indian College, but I want to get at the ground truth, what it was really like to be a student at Harvard College in the 1600s.”

To that end, Fash says, he hopes today’s students will locate a signature of the actual building – say, an outbuilding, flooring, or a “lipscar,” which is where the flooring meets the wall. “A privy would be great,” he says. “A privy is pay dirt for archaeologists. Everyone throws everything into the privy.” No architectural plans for the building remain in the Harvard archives; only descriptions of its whereabouts – along with class lists, letters, records of provisions, and so forth.

But that doesn’t matter too much, according to Fash. “Archaeologists are fond of debunking historical accounts,” he maintains. “We hope this will provide a richer view of what life was like for all the students at Harvard, whether Native American or not, and that it will allow today’s students to become actively engaged in the process of writing or rewriting the history of their own institution.”