Challenges of a modern storyteller

Rushdie talks about the novel, the real world, and the difference between the two

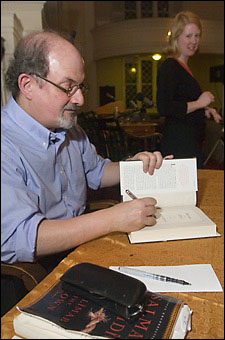

Salman Rushdie was at the First Parish Church in Cambridge on Monday (Nov. 7), to read from his new novel, “Shalimar the Clown,” and to discuss the challenges facing a storyteller in a politically troubled and morally perplexing world.

The event was jointly sponsored by the Humanities Center and Harvard Book Store, a partnership that will continue to bring prominent authors and intellectuals to Cambridge over the coming months. Homi Bhabha, the Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of English and American Literature and Language and director of the Humanities Center, introduced Rushdie and guided the ensuing dialogue.

“These discussions will be real conversations, not just publicity events,” Bhabha said in a later interview. “There will be a substantial intellectual core to them, where two people will be sitting down to seriously talk about issues central to the author’s work.” The next writer in the series will be economist Amartya Sen.

At Monday’s event, Rushdie read several passages from his novel, which begins with a tender love affair between the title character, a young apprentice tightrope walker, and the beautiful dancer Boonyi. Shalimar and Boonyi live in Kashmir, which Rushdie describes as a paradise, both in its physical beauty and in the determination of its Hindu and Muslim inhabitants to live lives of benevolence and tolerance. But, as Rushdie interjected, “There are snakes in this paradise.”

One source of discord is the Indian military presence, sent into the region to “protect” the inhabitants, and which they are prohibited by law from criticizing. The other is a mysterious religious figure known as “the Iron Mullah,” said to be engendered out of the heaps of rusting military hardware left over from the last war, who exhorts the Muslim villagers to engage in a holy war against “godlessness, immorality, and evil.”

Boonyi marries Shalimar but later leaves him to become the mistress of a wealthy American ambassador to India, with whom she has a daughter. Her betrayal embitters Shalimar and turns him into a ruthless jihadist who tracks his rival to Los Angeles and murders him.

Following the reading, Bhabha began the discussion by asking Rushdie about his tendency to use nonrealistic forms such as fable and allegory in his fiction.

“Well, you and I know that allegory is an Indian disease. In India everything is allegorical. Lunch is allegorical.”

Rushdie, who was born in Bombay and educated in England, went on to explain why he finds it impossible to adapt the approach of the great 19th century practitioners of realistic fiction to his own experience.

“Realism depended on the writer and reader having a shared description of what the world was like, a shared worldview. But today, reality is highly contested. There’s a real debate about the simple nature of what is the case, and in that context, the realism of the 19th century novel is not workable. It seems like a fiction.”

Rushdie said storytelling methods that depart from straight realism, “the game-playing, allusive, fantasticated forms, let in multiple points of view and seem closer to truth than naturalistic fiction. Allegory and fable seem better suited to this weird time.”

But Rushdie’s preference for allegory and fantasy is limited to his fiction. When it comes to the world itself, he seems quite committed to engaging with it on a purely pragmatic basis. This became clear when he made a plea for donations to help the victims of the recent earthquake in Pakistan, which devastated the very region of Kashmir that he writes about in “Shalimar the Clown.”

“Please give money, because the money that has been raised so far is absurdly inadequate. The winter is coming, and the Himalayan winter is not a joke. More people could be killed by the winter than died in the earthquake.”

Later, a member of the audience asked Rushdie whether he would have incorporated the earthquake into his book if it had happened earlier.

“No,” he said. “The literal problem of the earthquake is much more important. I wouldn’t know how to incorporate it into fiction because the most important aspect of it right now is fact.”

Returning to the subject of fiction, Rushdie remarked that immigration has been one of the principal forces responsible for changing the world from what it was in Charles Dickens’ time, and destroying the sense of a shared reality on which novelists relied. In the 19th century, London was essentially an English city, where the sight of an Indian or a black man was an unusual event. Today London is a multiracial and multiethnic metropolis.

Because of the homogeneity that once characterized English life, people had less awareness of the world outside, and novelists were able to portray their lives without reference to that larger world. A perfect instance is Jane Austen who wrote while England was at war with Napoleonic France, although one finds little hint of this conflict in her fiction.

“Jane Austen can spend her entire career without mentioning the Napoleonic Wars. The only function of army officers in her novels is to look cute at parties, to be objects of desire for the young female characters. But you don’t really need Napoleon to explain the lives of the Bennett sisters,” Rushdie said.

But in today’s world, immigration, mass media, and a globalized economy make it impossible for people to live such insular lives. As a result, the conventions of the realistic novel no longer seem adequate to portray the world of the 21st century. This is unfortunate, Rushdie said, because the novel seems more comfortable in the world of Austen, Dickens, and Flaubert than it does in ours.

“The novel does not want to live in a world like this. The novel wants to be about Madame Bovary living in a small town and having an affair because she’s bored. It’s much harder to write a novel about our world, but it’s important to try.”

The danger for a novelist responding to forces and events in the larger world is to become merely topical, Rushdie said. One of the ways in which he strives against this tendency in his own fiction is to focus on the characters as individuals.

“One has to remember, at the heart of the novel is the human figure. In this book, Shalimar gradually becomes a man of violence, but he’s from a community where everyone undergoes the same privations. Why does he become a man of violence when others don’t? This is where individual character becomes very important.”

This focus on the human figure is something that has not changed since the 19th century, Rushdie said.

“The reason Tolstoy wrote ‘War and Peace’ was not to describe the battle of Borodino. It was to write about the lives of his characters. The novelist has to make sure that human beings stay at the center.”