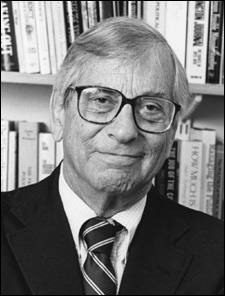

Richard Elliott Neustadt

Faculty of Arts and Sciences – Memorial Minute

At a Meeting of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences May 17, 2005, the following Minute was placed upon the records.

Richard Elliott Neustadt died in London, after a brief illness, on October 31, 2003 at the age of 84, only a few weeks after giving a guest lecture before Harvard undergraduates as part of a course on the presidency. On both sides of the Atlantic, his loss was mourned by family, colleagues, and former students as well as by many in public life, categories that frequently overlapped.

For someone who rarely sought attention, Richard Neustadt became arguably the best known and most influential political scientist in the last half century. His volume on Presidential Power, first published in 1960, sold more than a million copies. After seven years inside the Bureau of the Budget, he had seen the presidency up close. That experience enabled him to break away from sterile analyses of presidential powers to an appreciation of their inherent vulnerability.

The Constitution did not so much separate powers as it created “a government of separated institutions which share power,” Neustadt argued. The occupant of the Oval Office faces expectations that greatly exceed its formal powers. No matter how awesome those powers appear, the person in that office remains essentially a clerk, held in check by the multiple, often narrow, interests and personalities that surround him. To be effective, presidents have to learn how to persuade, a premise underlying an analysis that continues both to enlighten as well as to spark debate, assessments, and challenges.

As one of many future scholars to learn from their World War II experience, Richard Neustadt, upon graduation from the University of California at Berkeley in 1939 and upon receiving his M.A. degree from Harvard’s Department of Government in 1941, became an assistant economist in the Office of Price Administration, then joined the Navy, where he, as a lieutenant, was stationed in the Aleutian Islands. After the war, he returned to Washington to become a staff member within the Bureau of the Budget at a time when that office was bringing greater coherence to executive-branch operations. Balancing administrative expertise with political sensitivity became a necessity. Neustadt proved so successful at the task that he joined Truman’s White House staff.

Along the way, Neustadt found the time to complete his Harvard Ph.D., writing his dissertation on the legislative clearance function of the agency he knew best. When the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 limited his opportunities in Washington, he turned to the academy, focusing there on what he knew best. The transition was not an easy one. He first got a one-year job at Cornell. Then, in 1954 he applied for a similar position at Columbia, where, Neustadt later recalled, he was interviewed by David Truman, the leading political scientist of the day. “With a wife [Bertha Frances Cummings] and two children [Richard and Elizabeth] to support, and not so much as a nibble from any other university, I was an anxious interviewee. The extent of that anxiety I tried to conceal, I’m sure without success, but presently I forgot it in the intellectual as well as human interest of Dave’s conversation.” Under Truman’s tutelage and that of Wallace Sayre, two of the great pluralist thinkers in American politics, Neustadt discerned a way to connect his practical experience to a deep scholarly tradition.

The book that emerged was too adventurous to be an immediate success, however. Four publishers deemed it unworthy of publication. Finally, John F. Wiley, at David Truman’s insistence, agreed to take a risk, one that was amply rewarded when the New York Times pictured President-elect John F. Kennedy with the work under his arm. Shortly thereafter, Neustadt helped Kennedy with the transition to the new administration.

Despite this close association with Presidents Truman and Kennedy and his vigorous public opposition to the Vietnam War during the Nixon Administration, Neustadt’s analysis of the presidency transcended party boundaries. On his 80th birthday, he was presented with a copy of Presidential Power inscribed by all the then living U.S. Presidents – Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. All knew him, thought highly of him, and indicated that they had benefited from his insights. It is hard to think of another political scientist for whom such a statement would be true.

The art of persuasion came naturally to Dick Neustadt, an appropriate moniker for one who was so open-minded, under-stated, and good-natured. When he accepted an appointment within the Department of Government at Harvard in 1965, Dick soon plunged into the complex task of building the Kennedy School of Government, searching for common ground between those within the university who sought to create a new school of government and those who thought the traditional Departments were more than adequate to the task. Many doubt the new school could have been established without his quiet but steadfast efforts.

In his later years, Dick strengthened ties between two lands he came to love – the United States and the United Kingdom. His book, Alliance Politics, demonstrates a keen understanding of and appreciation for two systems and cultures that have learned much from one another. That appreciation deepened after his second marriage, following his first wife Bert’s passing, this time to their great friend Shirley Williams, a life-long British politician who co-founded the Social Democratic Party.

Dick Neustadt loved his students, undergraduates who flocked to his course on “The American Presidency,” and graduate students who benefited from his gentle prodding. He was in many ways a remarkable role model – scholar, public servant, teacher, mentor, above all, husband and father. His devotion to Bert and Shirley as well as his abiding love for the others in his family reveals that this was a man who understood the things in life that truly matter most.

Respectfully submitted,

Matthew J. Dickinson

Ernest R. May

Roger B. Porter

Sidney Verba

Paul Elliott Peterson, Chair