Pastor, mayor, and ‘go to’ man at Otis

New Orleans evacuees on Cape Cod have a friend

You understand why he has been dubbed “Mr. Mayor” when you walk around the Otis Air National Guard Base with the Rev. Jeffrey L. Brown, who was appointed by Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney to oversee the temporary base for more than 200 people evacuated from the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina.

When Brown goes a few steps in any direction, residents seem to come out of nowhere to shake his hand and share the trials – and rays of hope – in their uprooted lives.

Left, a young resident at the Otis Air National Guard Base finds a nice balance between the equally demanding activities of shooting hoops and eating a Popsicle, while Brown (in background, center) and others talk together. Right, visitors sit at a picnic table as kids play catch.

Left, a young resident at the Otis Air National Guard Base finds a nice balance between the equally demanding activities of shooting hoops and eating a Popsicle, while Brown (in background, center) and others talk together. Right, visitors sit at a picnic table as kids play catch.

“I’m not going back yet,” a bearded man tells him, a hint of fear in his eyes. “I talked to my uncle today and he said there are still dead dogs floating in the water!” Brown commiserates, and thanks the man for having shared a Louis Armstrong CD with him. “I just got a Billie Holiday one,” the man says, smiling.

Brown waves at another man, who comes up and says excitedly, “We’re moving to Cambridge, so that means we’ll be able to go to your church.” Brown rejoices with him and then relays information he’s dug up to help the young man achieve his goal of becoming a Massachusetts police officer.

At one point, Brown steps aside to convene with a couple. It turns into a pretty long meeting. Afterward, he explains that they were discussing what to do about what he called a clear case of housing discrimination.

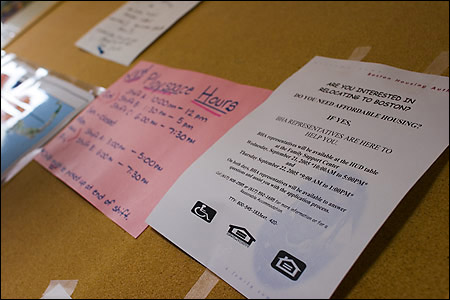

Since the residents arrived at Otis (also known as Camp Edwards) on Sept. 8, Brown has addressed “just about every request and complaint you could imagine,” from small problems like “trying to find fishing poles” to big issues such as dealing with tensions within the group and between group and community, and helping people to figure out whether they want to stay in Massachusetts or return to New Orleans. For those who have decided to stay, Brown and staff from governmental and nongovernmental organizations are helping the evacuees find jobs and housing.

Brown has been well known in Boston for a long time, as pastor of Union Baptist Church in Cambridge since 1987, a co-founder and co-leader of the Boston Ten Point Coalition, and an active member of the Black Ministerial Alliance. Since fall 2004, he has also served as the Baptist denominational counselor at Harvard Divinity School (HDS), advising students from a range of Baptist denominations and teaching classes on Baptist polity. He attended HDS in the early ’90s to work toward his Th.D., but, he explains, “then Jesse McKee got killed [in the infamous 1992 Morningstar church gang killing], I started working with Ray [Hammond] and Eugene [Rivers], and that work [the Ten Point Coalition] took over.”

Brown quickly became known for his ability to mediate between gangs and between gangs and city officials, as well as for his talent at bridging divisions among local black ministers. Soon, Brown was being invited to share his skills with groups throughout the country and the world.

Whatever title Romney or others may bestow upon the man who took on this daunting role at Camp Edwards (Brown says he would prefer “humanitarian coordinator”), it is clear that his years as a pastor and mediator have made him the kind of leader who cares about the spiritual needs of people as much as their physical needs.

“The majority of the people here are religious, and some are very religious,” Brown said, “so they have been talking about their experience in God language, and they use me as a sounding board.”

“Many folks here are going through the grieving process – some have lost family and best friends and they’ve all lost their homes,” Brown said. What’s more, “some of them had never stepped out of their neighborhood before, and now here they are in a strange land called ‘Cape Cod.’”

It’s not surprising, then, that many guests are reassessing all kinds of things in their lives. “When people have experienced such amazing upheaval, they feel the depth of despair,” Brown said. “They need reassurance that they can overcome and not just ‘cope’ with what’s happened to them.”

To that end, Brown decided, “I wanted to make this place not just a way station, but a safe space where people can begin to heal, piece together their lives, and to create new tools that they can take with them the rest of their lives.” Thus, upon assuming his role at Otis, Brown immediately insisted that the people be called “guests” or “brothers and sisters” as opposed to the more impersonal “evacuees,” and went about “assembling the essential elements for a town.”

The residents live in three National Guard barracks in a somewhat foreboding-looking compound that Lt. Col. William Tyminski, public information officer for the environmental and readiness center of the Massachusetts Military Reservation, says is “pretty typical for military housing.” One building houses families, another single men, and the third is the “pet dorm” (among the residents are several dogs and cats, a bird, a python, and some kind of lizard – whenever the lizard was mentioned, much debate ensued as to what kind it was). Tyminski said volunteers from the Southern Baptist Convention arrived recently to take over running the kitchen. Residents can go to the mess hall any time of day and find food, drink, and tables set up by various social service agencies.

Nineteen school-age children have been taken in by the town of Bourne schools, and after-school tutoring is provided on-site. Companies and individuals have donated a wide range of goods, including cell phones and regular phones, hairdressing services, bikes, and clothing (several guests were wearing Red Sox and Patriots clothing and hats). Halloween decorations hang from a tree, there is a small playground for children, and residents play together on the basketball court.

Perhaps the best testimony to Brown and the Otis staff’s success in making people feel welcome in a place that is terribly far from home is the high number of people who have elected to stay in Massachusetts. Brown said at least 88 of the original some 230 people have made the decision to relocate to the Boston area, while 32 are planning to go back. Others continue to mull over their decision. As of early October, 70 residents had already either returned home or moved into new homes in Massachusetts, leaving 163 people left on base. Within the past few weeks, that number is down to close to 100.

Speaking in early October, Brown wanted to quash all rumors that anyone is going to be “kicked out” of Otis, but explains that with the approaching winter, there is some urgency about getting people into warm, secure housing. “We had a chilly night here last week,” he said, “everybody was clamoring for more blankets, and I told them, you haven’t even seen cold yet!”

Even though he is the “go-to” person for everyone’s problems and needs, Brown is ever the pastor, talking only of the strength he witnesses among people despite the trauma they have experienced. “What has amazed me most is the amount of resiliency the people here have, once they know they have some hope to get to a better day,” he said. “These are proud, hardworking folks. They are already bouncing back.”