Administrators learn on the job

‘Harvard Stars’ series brings classroom to the office

Doug Melton recalled looking at frog and salamander eggs in a pond when he was a child and wondering how the individual egg knew whether to make a frog or salamander.

Melton, Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences and director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, is still wondering how egg cells know what to do, only now he is focused on human eggs and the stem cells they produce.

Melton gave a glimpse into his past as he talked about the future of science and politics to an audience of Harvard administrators Friday (Oct. 7). Melton likened the current spirit around stem cell science to the excitement that must have pervaded the physics community at the discovery of the transistor.

“This is an area of biology that has the potential for enormous growth,” Melton said. “I believe the 21st century will be the century of cells and of stem cells.”

Melton spoke to about 60 Harvard administrators gathered in Sever Hall for a Harvard Administrators Forum. Fran Feldman, a member of the forum’s steering committee, said the talk was part of a series called “Harvard Stars,” which is designed to give Harvard’s administrators a chance to hear from the University’s world-class faculty.

“This is designed to give us, the University’s administrators, a very brief taste of what it’s like to be a student at Harvard and to see what makes Harvard such an interesting place – its stellar faculty,” Feldman said.

Melton’s talk, “Scientific and Political Challenges for the Stem Cell Institute,” illustrated the value of a diverse place such as Harvard to an entity such as the Stem Cell Institute. With stem cells at the middle of a political and philosophical debate, the institute’s work draws on a wide range of fields, including science, politics, law, business, philosophy, and religion.

“We have thought leaders in all these areas,” Melton said.

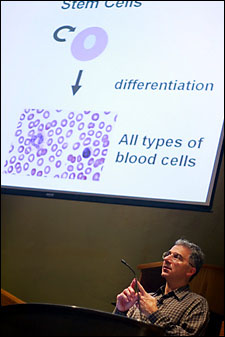

Melton gave an overview of stem cell biology, telling the group that stem cells can both renew themselves and differentiate into other cells. There are two main kinds of stem cells: adult stem cells and embryonic stem cells. Adult cells are found in various kinds of tissue and help renew that tissue.

Skin stem cells, for example, renew the skin of a person’s face every two months, Melton said, so even though one may see the same image when looking into a mirror, it’s a whole new face every two months.

While adult stem cells are preprogrammed to make only one type of cell, embryonic stem cells can develop into any type of cell in the body. This makes them potentially useful in treating tissue-related diseases, such as diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease.

Melton’s own research centers on diabetes and in making the pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin. Melton described his research as searching for the signals that prompt an embryonic stem cell to develop into a pancreatic cell.

“There are 25,000 genes in the human genome,” Melton said. “We need to know what gene turns on, when and where, in order to make a pancreatic beta cell.”

Melton described the process of harvesting stem cells from donated embryos, fertilized and frozen, but unused, at in vitro fertilization clinics. The stem cells are taken from a tiny lump of cells called a blastocyst.

Because the embryo is destroyed in removing the cells, embryonic stem cell research has attracted controversy, both from those who believe human life begins at conception and those who Melton described as “tangled up with the tortured politics of abortion.”

Melton said questions of when life begins may be better phrased as when “personhood” begins, since many things are alive, including sperm and egg cells, on which no particular moral value is placed.

The question of where the person begins in the process of growing from a fertilized egg into a baby – is one that science probably cannot answer, Melton said. That means the answer has to come from society more broadly, he said, urging audience members to talk to their legislators on the subject.

Melton said he didn’t think that personhood begins with a fertilized egg, because we routinely discard them at fertilization clinics and millions of fertilized eggs fail to implant into the uterus and are discarded by the body.

The controversy over embryonic stem cells led the federal government to ban federal funding for research on embryonic stem cell lines created after Aug. 9, 2001. That funding cutoff has had a chilling effect on embryonic stem cell research in the United States, said Melton, adding that South Korea has taken the lead in this area.

However, Melton said he believes that one big breakthrough would change the political climate around stem cell research by showing what a powerful tool such research can be.

“I’m a hopeful person,” Melton said. “I think it’ll only take one success, one big breakthrough, to have the federal government rethink its policy.”