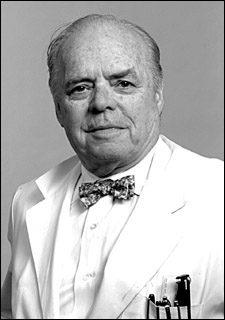

Thomas B. Fitzpatrick

Faculty of Medicine – Memorial Minute

At a Meeting of the Faculty of Medicine December 15, 2004, the following Minute was placed upon the records.

Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, whom many credit with re-inventing the disciplines of clinical and investigative academic Dermatology over his 40 year career at Harvard, died at his home on August 16, 2003. He was 83 years old. From 1959 to 1987, he served as the Chairman of the Department of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Dermatology Service at Massachusetts General Hospital. His impact on his chosen field was enormous, and included seminal scientific contributions, an unparalleled track record in teaching and training, and significant innovations in clinical treatment of skin diseases. Until the final year of his life, he participated vigorously in patient care, and was considered by many one of the world’s leading dermatologists.

He was born in Madison, Wisconsin, on December 19, 1919, and grew up in that state. After completing his undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin, he received his MD at Harvard Medical School and interned at Boston City Hospital, where he was struck by the difference in the level of scientific rigor and sophistication between Dermatology and other medical specialties. He was determined to change that, and spent his next two years at the University of Minnesota obtaining a PhD in Pathology. Two years in the army during World War II were spent at the Army Medical Center. There he met and initiated a fruitful collaboration with Aaron Lerner, MD, PhD, on the biology and chemistry of skin pigmentation. After a fellowship at Oxford in chemistry, he undertook clinical Dermatology training at the University of Michigan and the Mayo Clinic, all the while pursuing his research in melanocyte biology. His success was such that he was recruited to be Professor and Chair of Dermatology at the University of Oregon at age 32. A mere seven years later, he was recruited to Boston to assume the Chair of the HMS Dermatology Department. At age 39, he was Harvard’s youngest Professor and Chair.

Dr. Fitzpatrick served as Chair of the Harvard Department of Dermatology from 1959 to 1987. During that time, the Department grew from a handful of full time academic dermatologists at the Massachusetts General Hospital who trained three residents to an entity that included divisions or departments at Beth Israel Hospital, Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dana Farber Cancer Institute and trained 15 residents. During his tenure, academic dermatology evolved nationally into a rigorous specialty encompassing cutting edge research, teaching, and patient care, in no small part due to his energy, passion, and influence. The training program at Harvard rapidly became known as the place to be if one was interested in a career in academic dermatology. It produced more than 50 full time academic faculty and 12 department chairs including the present Chair of HMS Dermatology, John A. Parrish, MD. In 1971, he established the first comprehensive, multi author textbook in the field – Dermatology in General Medicine – currently in its 6th edition. This was the first dermatology textbook to be widely used by people outside the field, and marked the maturation of academic dermatology into a respected medical specialty. Fitzpatrick was an able scientist, a gifted teacher, a master clinician, and a towering leader and humanist in his field.

His important basic science contributions included the discovery and demonstration of human tyrosinase, fundamental to the synthesis of melanin, and the discovery of the melanosome, the basic metabolic unit of melanin synthesis. He developed the concept of the epidermal melanin unit, a collaborative cellular relationship between a melanocyte and contiguous keratinocytes through which pigment was exchanged, fundamentally changing our understanding of the dynamics of epidermal pigmentation. Based on his understanding of the UV absorbing properties of melanin, he promoted a rational approach to the development of topical sunscreens.

His clinical research contributions were equally profound. With Drs. Mihm and Clark, he developed rigorous clinical criteria for the rational early diagnosis of malignant melanoma. With these physicians and the surgeon Dr. John Raker, he established the first Pigmented Lesion Clinic in 1966. This clinic became a model upon which many other such clinical functions were founded. With Dr. Arthur Sober, he convincingly argued for a role of sunlight in the etiology of melanoma. This reinforced the concept of cancer prevention through volitional modification of behavior; one of the first examples of what is now common practice. Other contributions included the identification of the ash leaf spot as the earliest sign of tuberous sclerosis, and work on macromelanosomes in neurofibromatosis.

He was a translational researcher long before the term was coined. The best example of this was his work with psoralens and photochemotherapy. From ancient observations that psoralens permitted hyperpigmentation in vitiligo, Fitzpatrick and his colleague Pathak studied the photo- and biochemistry of psoralens in the laboratory. With Parrish, who had studied the photobiology of ultraviolet A (UVA), Fitzpatrick and his colleague developed the idea of photochemotherapy, where a patient would ingest a dose of psoralens prior to receiving a controlled dose of UVA to his or her skin. The treatment, known as PUVA, became the most effective treatment for psoriasis and a variety of other T cell mediated skin diseases for decades after, and is frequently used even today for these diseases.

Fitzpatrick’s ability to teach Dermatology was legendary. From his world famous textbook to his trademark observations at grand rounds, he had a gift for distilling the essence of the problem, describing it fully, and offering rational and often inspired solutions for clinical problems. He was able to convey his enthusiasm for the field to medical students who had little background in Dermatology, many of whom became hooked on the field after spending time with him. With residents, he was demanding but so clearly dedicated to their education and accomplishment that they worked tirelessly to live up to his expectations. Both junior and senior faculty could continue to learn from this extraordinary teacher whose encyclopedic knowledge, clarity of thought, and unique insights made every clinical conference a didactic experience.

As a clinician, he was unparalleled. Until months before his death, he took referrals from around the world, and the toughest cases that had stymied the best clinical minds in dermatology made their way to his door. He never turned down a case, and his practice included the famous and wealthy as well as the average citizen of Boston. He consulted on both inpatient and outpatient services, and was famous for his practice of consulting well-worn textbooks in front of patients – he had not the slightest ego invested in proving to patients that he knew it all. He was passionate about his patients and their care, and they knew it and were deeply appreciative. His great gift was to give each individual patient such undivided attention that the patient felt the most important person in the world for Dr. Fitzpatrick during their encounter.

Outside of Boston, he will be best remembered for his extraordinary leadership in dermatology. There is general agreement that he had as profound an effect on this field as anyone else in the field, before or since. He has been President of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, the Association for Professors of Dermatology, and the International Pigment Cell Society. He co-founded the Dermatology Foundation, also serving as its president, and he is credited for the original idea that led to its establishment. Today, this thriving society is the major non-governmental source of funding for young investigators in investigative Dermatology. He has served as a consultant to the National Institutes of Health, FDA, National Academy of Sciences, and many other important policy-setting entities. He was an ambassador for Dermatology around the world, traveling and teaching widely. He was particularly proud of his work in Japan shortly after World War II. Over the next decades, many Japanese dermatologists traveled to Harvard to study with him, and many are now Department chairs. His close relationship with Japanese academic Dermatology over the years led to his extraordinary reception of the “Order of the Rising Sun” from the Japanese government in 1987.

A testament to his extraordinary career was the establishment of an endowed chair at Harvard Medical School in 1982, an honor rarely accorded to an incumbent professor. His most contagious gifts were his inexhaustible curiosity and his genuine joy in his work, traits that were transparent to his students and colleagues and inspired them to act in kind. His leadership was measured not so much by the number of people he led, but by the number of leaders he created.

Fitzpatrick was an avid music lover, an accomplished pianist and an expert on Johannes Brahms. One of his proudest accomplishments was to be chosen to serve on the Board of Overseers of the Boston Symphony. He frequently visited other musical organizations throughout the world to develop new ideas for his beloved BSO.

Fundamental to his success, curiosity, joy, and outlook on life was his nearly 60-year partnership with his wife Beatrice Devaney Fitzpatrick, who survives him. Together they contributed a daily feature in the Boston Globe magazine called “Thoughts for the day”, and shared every feature of their lives together. Their union produced five children and three grandchildren.

We are very sad that this giant talent, Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, has passed away, but gratified as we reflect on the enormous and enduring influence his life has had on dermatology and medicine.

Respectfully submitted,

John A. Parrish, M.D., Chairperson

Thomas S. Kupper, M.D.

Martin C. Mihm, M.D.