Reclaiming religion from the right

Religious activist outlines path for new national dialogue

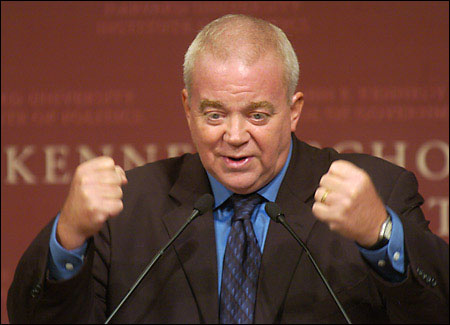

Divinity School lecturer and evangelical Christian leader Jim Wallis said the time has come to end the religious right’s monologue on national moral values and begin a new, broader-based dialogue that goes beyond a fixation on gay marriage and abortion.

Wallis, a self-described progressive, said the nation’s liberals long ago ceded national religious discussion to a small, conservative minority that has successfully defined the debate around a narrow agenda.

Liberals forget, he said, that the major reform movements in our nation’s history, from abolition to civil rights, were begun by spiritual leaders.

“Lyndon Johnson didn’t become a civil rights leader until Martin Luther King made him one,” Wallis said. “Where would we be if they [religious leaders like King] kept their faith to themselves?”

Wallis spoke at the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Monday (Sept. 26). The event, “God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It,” was sponsored by the Institute of Politics.

Wallis, visiting lecturer on religion and society at the Harvard Divinity School, has traveled widely to speak about religion, ethics, and public life. He was a founder of Sojourners: Christians for Justice and Peace and still serves as the editor of Sojourners magazine, which covers faith, politics, and culture. He is a regular commentator on television and radio, and his columns have appeared in major national newspapers. His most recent book, with the same title as Monday’s talk, was published this year.

Wallis was introduced by David Gergen, public service professor and director of the Center for Public Leadership. Gergen said religion has been both a divisive and unifying issue in America, and called the issue of religion in public life “so combustible we dare not take our eyes off it.”

Though it has been virtually ignored by the religious right, Wallis said he believes that fighting poverty is the major moral issue of the day. The stark images in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina have stripped away the national denial about the issue, he said, and highlighted not just New Orleans’ poverty, but the link between race and poverty.

Almost 3 billion people worldwide subsist on less than $2 a day, Wallis said, adding that we live in a time when the means to alleviate poverty exist even though the political will is lacking.

“I am an evangelical Christian and I’ve found 3,000 verses in the Bible about helping the poor. So I think that helping the poor is a moral value issue,” Wallis said.

Other topics important to progressives are also important morally and religiously, Wallis said. Saving the environment, he said, is important because it is taking care of “God’s creation.” And opposition to the war in Iraq has been echoed by spiritual leaders around the world, he said.

Wallis told of his recent appearance on Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” where he asked, “How did Jesus become pro-rich, pro-war, and only pro-American?” The show generated thousands of e-mails, he said, from people who said they lost their faith because of television evangelists and sex abuse scandals and from people who said they didn’t know you could be a Christian and still care about poverty, the environment, or the war in Iraq.

The most recent presidential election exposed the national divide over religion, Wallis said. No matter which candidate won, he said, half the nation felt crushed due to their faith and moral values. The election showed how religion is used in the halls of power and had people around the country saying “I’m a person of faith and that’s not my faith,” or “I’m a person of moral values, and those are not my moral values.”

Those divisions were illustrated on his most recent book tour, Wallis said, when he encountered people who seemed there not so much to get a book signed but to find alternatives to the narrow national debate.

He met many people from a variety of faiths who felt left out of the national religious dialogue, including Jews, Muslims, evangelical Christians who didn’t share the concerns of those who had the national ear, Catholics who felt that bishops who focused only on abortion didn’t speak for them, leaders of black churches who had been left out, youth who described themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” and people who feel that religion doesn’t have a monopoly on morality.

Wallis called for a unifying discussion that seeks common ground, rather than lines of division, particularly on reducing poverty. Even on such polarizing issues as abortion, both sides can agree that it is important to work to reduce unwanted pregnancies and together, he said, can make important progress.

“To create a mirror image on the left would be a mistake,” Wallis said. “Religion is best when it’s not ideologically predictable or loyally partisan.”

Religion works best in the national moral discussion when it works not to change individual politicians, but to change the national mood. Change the national political “winds,” Wallis said, and politicians will follow.

“I believe the role of religion is not to be a wedge and a divider. It is to be a wind changer,” Wallis said. “Hope means believing despite the evidence, and then watching the evidence change.”