Divine progress

Divinity School convocation marks a half-century of School’s admission of women

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) held its convocation Sept. 20, marking the 50th anniversary of the School’s admission of women.

Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers was on hand to congratulate the School on its half-century of progress.

“I am very pleased to participate in the 50th anniversary of the admission of women to Harvard Divinity School and to reflect on the progress that has been made at the University toward greater gender equality,” he said.

“In many ways, Harvard Divinity School has been ahead of the game,” Summers added. “In 1955, women were first admitted to the School, and by 1980 they were in the majority and continue to be so. During this time, the School has supported many studies and research projects that have contributed to our understanding of gender and society and provided insight into the cultural and religious changes in the world around us.”

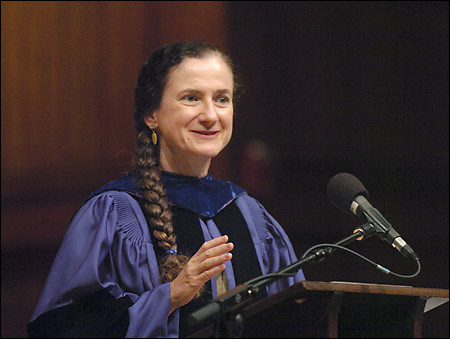

Ann Braude, senior lecturer on American religious history and director of the Women’s Studies in Religion Program, gave the keynote address, titled, “A Short Half-Century: 50 Years of Women at Harvard Divinity School.”

Braude focused on three historical moments illustrating the struggle of women to establish a presence at the School. The first of these occurred in 1893 when a group of HDS alumni petitioned the Harvard Board of Overseers to approve the admission of women.

The board rejected the petition as “unwise and impracticable.” President Eliot, who sought to broaden the pool of male candidates to the University, was nevertheless firmly against the admission of women to Harvard classrooms. Coeducation is particularly undesirable in large cities where people of all classes are thrown together, he said, because under such circumstances “unpleasant associations are formed and disastrous marriages result.”

Braude skipped ahead to the 1955 convocation when HDS welcomed its first eight women candidates. Many of these went on to distinguished careers as ministers, educators, and scholars, and several, Braude pointed out, were present at this 2005 convocation. Among them was Constance Fern Parvey, a former Lutheran chaplain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who gave a reading following Braude’s talk.

The admission of women to the School coincided with a period of general rebirth under the direction of HDS Dean Douglas Horton, whose tenure also began in 1955. In his convocation address, Horton remarked that HDS was finally following the advice of Anna Maria Shuman who was admitted to study theology at Frisian University in Holland 300 years before and whose dissertation asserted that “the study of letters is becoming to a Christian woman.”

The 1950s not only saw the admission of women, but also the founding of the Center for the Study of World Religions and the establishment of the Department of the Church, which became the Office of Ministry Studies. From a near-moribund institution, concerned only with providing training in biblical scholarship and Christian history and doctrine, the School grew into a dynamic center of social and ethical debate, and became fully engaged in the preparation of candidates for the ministry.

But while 1955 marked a milestone for women, it was not until 15 years later, under the influence of the feminist movement, that women began to be represented in significant numbers, either as students or faculty. This was the third and last moment described by Braude, when the ordination of women became a topic of debate in religious communities throughout the country and the world.

“In every one of those communities the religious leadership of women was far more than a question of access to education. It required a fundamental rethinking of the meaning of texts, doctrines, practices, and history in a way that was not required by women’s entrance into most professional schools,” Braude said.

Krister Stendahl, a Swedish theologian, who became dean of the School in 1968, was fully supportive of this change, so much so that women students referred to him affectionately as “Sister Krister,” Braude said. Under Stendahl’s leadership, the School became open to re-examining religion through the lens of gender. One example was Harvey Cox’s course “Eschatology and Politics” in which students decided to halt the use of masculine pronouns to refer to all people or to God, and to respond to the use of gender-exclusive language in class by blowing on kazoos.

Braude concluded by saying that the history of women at HDS illustrates the intellectual benefits of being an outsider.

“If you feel like an outsider to this august institution, you are in very good company,” she said. “Almost everyone I know feels like an outsider here, either because of their religious commitments or their lack of them, because of the particular background and vantage from which they approach the study of religion, their disciplinary commitments, their national origin, their race, or their sexual orientation, or all of the above.”