Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy extended five years

Teens credit it with building confidence

The Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy (CHSA) celebrated its fifth anniversary this summer. Now, thanks to funding from Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers’ office, it is set to operate for another five years.

There are two groups for which this is welcome news. One is made up of candidates in the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s (GSE) Teacher Education Program who gain valuable experience working with students under the close guidance of experienced mentor teachers in preparation for student teaching during the following school year.

The other group is composed of local high school students who enroll in CHSA courses in math, literature, history, biology, physics, or chemistry, either for enrichment or to make up course credits. The students who’ve been advised to spend a portion of their summers at CHSA may have a hard time believing at first that the program’s continued operation is a cause for rejoicing, but judging from past experience, they will change their minds.

“I think the academy gives them something they probably don’t get during the school year,” said Christopher Lohse, a physics teacher with five years’ experience in inner-city Los Angeles schools who taught in the program last year as an intern and returned this summer as a mentor teacher. “In the academy, they have four adults working with them constantly, and so it’s very difficult for them to fall through the cracks. They’re also exposed to the enthusiasm of the Harvard interns, and they respond very quickly to this new kind of energy they’re seeing.”

The CHSA is open to any student who resides in the city of Cambridge, from rising eighth-graders to high school seniors, and welcomes both private and public school students. The program is free of charge and offers students the opportunity to gain credit for missed or failed courses or to accelerate their learning by taking courses for enrichment. This past summer, nearly 300 students enrolled in CHSA.

For students in the GSE’s Teacher Education Program, CHSA often represents one of their first real teaching experiences in a diverse, urban classroom.

“This was a really good opportunity to be able to teach and to have the support of experienced teachers, ” said Christina Feo, a master’s candidate from California who taught algebra classes to 11th- and 12th-graders this summer. “This is the first time I’ve taught in a school where I was responsible for grading students, and it was great to be able to get my feet wet without having to deal with huge classes or with going out and doing it alone.”

Surveys of students who participate in the academy indicate that the six-week program is an enjoyable and confidence-building learning experience, in large part because of the high teacher/student ratio. One mentor teacher and three interns typically teach each of the smaller-than-average classes.

Typical of the kind of comments students make in their evaluations of their experience are the remarks of one young woman who went through the program two years ago:

“Summer school is just so different and a place I look forward to. … I got help when I needed it. And usually when I get help I feel weird and uncomfortable, and this time I felt loved. … Sometimes I feel like a superstar. … It is almost better than having a boyfriend.”

Follow-up studies have also shown that the positive experiences students have in the academy continue to impact their performance during the school year.

“It’s a challenge for teachers to build an atmosphere where kids are willing to take chances and help each other. But because the students have so many more adults relating to them, many of them spark up to school and become more confident about the upcoming school year,” said Raegen Miller, an instructor and advanced doctoral student at the GSE who teaches mathematics at a local charter school.

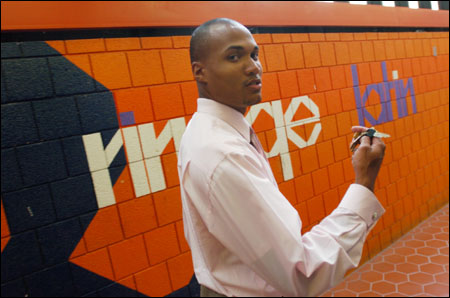

Raegen Miller (left) is an instructor and advanced doctoral student at the GSE who teaches mathematics at a local charter school. CHSA student Carlos Ribeiro works on a project for his class in U.S. history-a poster on the life and career of Malcolm X.

Raegen Miller (left) is an instructor and advanced doctoral student at the GSE who teaches mathematics at a local charter school. CHSA student Carlos Ribeiro works on a project for his class in U.S. history-a poster on the life and career of Malcolm X.

According to Lohse, one reason the program works well for high school students is that teachers have an opportunity to engage them in what he calls “meta-cognition,” or thinking about thinking, something there is rarely time for during the school year.

“We might ask a student, ‘Can you tell us what you were thinking when you said that?’ And their answer might reveal hidden misconceptions, or it might reveal a richer thinking about the question than we anticipated.”

At the same time, these intensive interactions with students can help even experienced educators to hone their teaching skills.

“From a mentor’s perspective, being able to think through your pedagogy makes you all that more effective as an educator,” Lohse said.