Soldiers Field

The story of a monument, the man who built it, and the men it honors

…in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing….

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1884

“When I became athletic director in 2001,” Robert Scalise recalls, “I wanted to build on the proud traditions of Harvard athletics. I am delighted that I have been involved with the care and preservation of the Soldiers Field Monument. We have moved the marble original into the Murr Center – a safe place, away from the elements. An exact copy in granite is now located just inside Gate One of Soldiers Field. Both will inspire future generations. They symbolize the finest values that a school can instill in its students.”

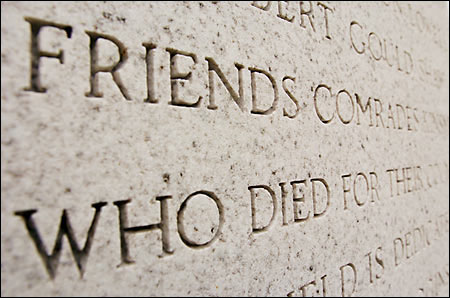

The monument honors six young men who died as a result of their service in the Civil War. Simple in design, profound in effect, the monument, through the values it represents, reaches out beyond its silent stand at the athletic fields.

The story of Soldiers Field begins in 1870, when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, his family, and a few friends gave 70 acres of meadowland on the Brighton/Allston side of the Charles River to Harvard College. In 1887, the poet’s son, Ernest, donated a strip of marshland on the southern side of Mt. Auburn Street, anticipating that the gift would “be a great boon to Cambridge when it becomes crowded” and feeling it was “more in harmony with [his father’s] character than any graven image that could be erected.” In 1882, John Owen, a graduate of the Harvard Divinity School, donated a small parcel of land adjacent to the Longfellow property. And, in 1890, Henry Lee Higginson, who is perhaps best known for founding the Boston Symphony Orchestra, donated 31 acres across the Charles River off North Harvard Street. Harvard College also bought 9 acres in 1890. It is the Higginson donation, which gave the tract its name “the Soldiers Field,” that perhaps has the most poignant significance.

During the Civil War, Higginson began his military service as a lieutenant in the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteers and then served as a major in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. In 1863, he was badly wounded at the Battle of Aldie with a sabre cut across his face and a pistol bullet at the base of his spine. Though he tried to return to active service, the pain from his wound prevented him from doing so.

The story behind the story

Helen Hannon’s campaign to correct the neglected condition of the Soldiers Field Monument came about through the unlikely combination of a conversation with historian Brian Pohanka and a day’s bird-watching by Janet Heywood, vice president of interpretative programs at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. Pohanka happened to mention to Hannon a Harvard student named Stephen George Perkins who had caught his interest in “The Harvard Memorial Biographies.” “The Biographies,” edited by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, were published in 1866 and tell the life stories of the Harvard Union men who died in the Civil War. Hannon, in turn, mentioned the Perkins name to Heywood, who later came across the monument while bird-watching at Soldiers Field. Heywood saw that Perkins was included on the list of names and told Hannon, who subsequently visited the monument. When Hannon brought the monument’s condition to the attention of the University, it was cleaned and a maintenance program begun. At that time, Albert H. Gordon generously stepped in to preserve the monument.

For all the horror and pain of the Civil War – it was also, for some participants, a great adventure. For many, it was their greatest adventure, leaving a lifelong impression. Maj. Higginson never forgot his war experience.

When Higginson formally transferred ownership of the 31 acres to Harvard University, it was his hope that the land would become athletic playing fields for the students of Harvard. He emphasized that the gift was without conditions – but he would like the grounds called “The Soldiers Field” and “marked with a stone bearing the names of some dear friends – alumni of the University, and noble gentlemen.” Five days later on June 10, 1890, 400 students and graduates heard Higginson’s “Soldiers Field” speech.

There is something special about friendships made in our early 20s. The world is full of life and promise and only the best is ahead of us. Space precludes quoting the full text of Higginson’s speech. However, to capture something of the character of his early, lost friends, here are some excerpts.

James Jackson Lowell. “First scholar in his class – thoughtful, kind, affectionate, gentle, full of solicitude about his companions, and about his duties.” Wounded early in the war, recovered, returned to service. Mortally wounded, Glendale, Va., 1862.

Robert Gould Shaw. “He was of a very simple and manly nature – steadfast and affectionate, human to the last degree – without much ambition except to do his plain duty.” Colonel of the African-American regiment – the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers. Killed, Fort Wagner, S.C., 1863.

Stephen George Perkins, “Still another fine, handsome fellow, great oarsman, charming companion, wit, philosopher, who delighted in intellectual pursuits and in his fellow creatures whom he watched with his keen eyes and well understood.” At Cedar Mountain, he was “too ill to march; but, with other sick officers left the ambulances because he was needed in this fight.” Killed, Cedar Mountain, Va., 1862.

Charles Russell Lowell. “A first scholar, because he couldn’t help it – full of thought, life and intense vigor – brimful of ideas – brilliant and strong beyond compare . . . always in the front, lost thirteen horses in his daring efforts to win success.” Mortally wounded, Cedar Creek, Va., 1864.

James Savage Jr. He “was courageous to the last degree.” While recruiting in Fitchburg the men “would turn to the ‘captain,’ as they called him, listen to his replies and then swear allegiance, as it were, to him. He, the quietest and most modest of men, was immensely impressive, for he was a real knight – just and gentle to all.” Mortally wounded, Cedar Mountain, 1862.

Edward Barry Dalton, “The last was a physician by choice and by nature, if intelligence, energy, devotion, and sweetness can help the sick.” He was in charge of the hospital camp at City Point, Va., with over 10,000 sick and wounded men. “Here he worked out his life-blood to save that of others.” Of the six men honored by Soldiers Field, only Dalton lived past the war. In 1866, he became the sanitary superintendent for the city of New York. His wartime malaria returned accompanied by complications from pleurisy. He moved to Santa Barbara, Calif., in search of a better climate, but his health gave way completely and he died in 1872.

In his speech, Higginson said “heaven must have sorely needed them to have taken them from us so early in their lives.” He hoped, he added, that the lives of these men would inspire the students to be “able and ready to do good work of all kinds – steadfastly, devotedly, thoughtfully; and that it will remind you of your own duties as men and citizens of the Republic.”

In gratitude for his donation, the students commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint Higginson. The portrait, located in the former Union, now the Barker Center, is striking and masterful. However, Higginson’s legacy to the community is not dependent on Sargent’s genius – but on his personal honor and ideals.

It is through the generosity of Albert H. Gordon ’23, that the exact copy has been erected on the grounds. Gordon’s support and contribution, combined with the efforts of fellow alumnus David Mittell ’39 saved the original monument from a slow disintegration. The new granite monument, done by Jerry Williams of the Barre Sculpture Studio in Vermont, will better withstand the New England climate. The installation was done by Francis Tash, also of Vermont.

Harvard University staff members who have lent their enthusiasm and time to the restoration and copying of the Soldiers Field memorial are Jeremy Gibson, Jon Lister, Dick Nerden, Warren M. Little ’55, Natalie Morris of the Athletic Department staff; Michael Lichten of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and Henry Lie ’76, director of conservation, Harvard University Art Museums. Edward Gordon, president of the Victorian Society/New England Chapter, also lent valuable support.

Historian Brian Pohanka calls the restoration of the Soldiers Field memorial a “noble and important endeavor. The fallen friends whom Higginson honored were exceptional people, young men of deep character and great potential whose deaths were a real loss to our country.”

Gibson, associate athletic director, says “This is a wonderful opportunity to contribute to a project that not only speaks to the preservation of Harvard’s athletic history, but also to Harvard’s role in the Civil War.”

The new monument stands through Gate One at the entrance to Soldiers Field; the original is in the Murr Center, both are located on North Harvard Street. They can be reached by crossing the Larz Anderson Bridge from Cambridge. The Anderson Bridge is also a Civil War memorial for Brevet Brigadier and Maj. Gen. Nicholas Longworth Anderson.

Special thanks to Janet Heywood, Henry Lee, Brian C. Pohanka, Anthony M. Sammarco, and the Harvard University Archives for their assistance.