KSG students help a city balance books

Cut costs for Somerville

When Bryan Richardson signed up for a lecture course on public finance at the Kennedy School of Government last fall, he never expected to be earning his grade by hobnobbing with urban police officers. “This material can be kind of dry in the classroom,” the 26-year-old from Tulsa, Okla., recalled. “We all hoped to apply what we were learning.”

Then one day Somerville Mayor Joseph Curtatone came to the class, taught by Linda J. Bilmes, a former assistant secretary of commerce in the Clinton administration, and all but pleaded for Richardson and his classmates to help the beleaguered city.

Somerville’s annual budget (which reached about $140 million in fiscal year 2005) was a mess, Curtatone said. No one knew how much it really cost to pave a road, or pick up a dead skunk, or respond to a three-alarm fire. Money was being disbursed willy-nilly for vital departments like police and public works without any real sense of whether the city was getting the most for its tax dollars.

“My point was, ‘How can I tap into Harvard,

this great nearby resource, and get help,’” Curtatone said. “I also wanted these students to have real-world experience.”

Richardson, who will graduate June 9 with a master’s degree in public policy, was one of 60 students who jumped at the chance to learn municipal budgeting from the curbstone up. Soon, he and the others were soon meeting with Somerville department heads and line workers, riding on fire engines, shadowing librarians, and accompanying police on foot patrols, all the while trying to calculate the price of each activity.

By the end of the fall semester, Bilmes’ class had issued recommendations on improving departmental efficiency, eliminating waste and duplication, adding automation, and making other changes. For example, the Kennedy School students helped Somerville discover that it was spending tens of thousands of dollars a year to collect apartment-building trash while taking in only 30 percent of those collection costs in fees from the property owners.

“It was fantastic, the way the students helped us capture the actual costs of these services,” Curtatone said.

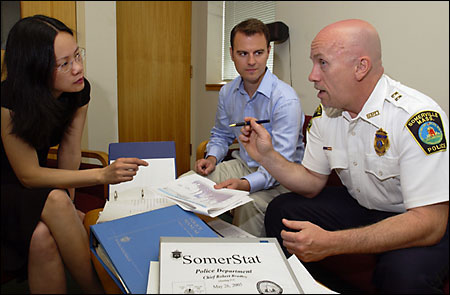

But that wasn’t enough for Richardson and a few others. They signed on for a spring follow-up class designed by Bilmes to let the students delve further into Somerville’s budgeting woes. Eyeballing police department records and spreadsheets, Richardson and his partner, Hien Dao, 31, a political and economic development concentrator who will also graduate with a master’s in public policy on June 9, spotted a problem: Somerville was spending $170,000 a year to administer a program for “detail officers” – police hired by businesses to provide security at public events or to manage traffic at construction sites. But the city was taking in only $100,000 a year in fees for those officers, for a net loss of $70,000.

“The detail program should not be costing the city money – if anything it should be making them money,” Richardson said. “We were not expected to be afraid to look for the negative. That’s the risk that was incumbent on Somerville when they agreed to lift the mat and let daylight into areas that have been dark for some time.”

What Mayor Curtatone, 38, was looking for in his alliance with Harvard, Bilmes, and her students is something increasingly in vogue among public policy experts and academics: activity-based costing, or ABC. In non-wonk terms, ABC boils down to calculating how much it really costs a municipality to do something – plant a tree, prepare a meal for the elderly, respond to a 911 call. The calculations are complex because many city functions will overlap different departments. But once the costs are estimated, a city like Somerville can, for example, judge whether it is spending too much to offer a ceramics class, or getting its money’s worth out of a youth basketball program.

“You don’t get an exact figure to the penny,” said Bilmes, who worked hand in hand with the Kennedy School’s Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston and its assistant director, Phineas Baxandall, to make the Somerville project happen. “But you get an estimated amount per program. It gives you a different way of understanding what you spend money on as a city.”

As Baxandall put it, “They will know how much it costs to fix a pothole rather than just the budget line item for asphalt and trucks.”

Bilmes, who as chief financial officer and assistant secretary for management and budget for the U.S. Department of Commerce from 1997 to 2001 was responsible for a $9 billion budget and the administration of 45,000 employees, is a bit of an evangelist of ABC budgeting, which is catching on nationally. Curtatone said Somerville, a Harvard neighbor that has rarely tapped into the University’s brainpower, is the first city in Massachusetts to give the ABC concept a true dry run.

“Mayor Curtatone and his team are turning little Somerville into one of the most innovative and dynamic places in the country, in terms of its budgeting,” Bilmes said. “I feel very fortunate that my students and I have been able to participate in this remarkable transformation.”

Bilmes said she was initially apprehensive about turning a class full of Kennedy School students loose on a city like Somerville.

“I had no idea how the students would perform; or how the city would react to them,” she said. “I couldn’t believe they were so good – the students loved the city officials and vice versa. I kept being told things like ‘They’re so punctual.’ City officials liked working with the students a lot more than paid consultants.”

Curtatone estimated he received more than $100,000 worth of invaluable free consulting work from the class. Richardson said he got something equally valuable for his time.

“I learned things here I can take right into my next job,” he said. “When I went to apply for federal jobs this year I was told this was a great item to have on my resume. This is a great area for the Kennedy School to move into. This is the future.”