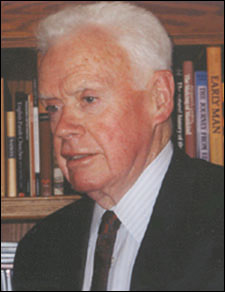

John Vincent Kelleher

Memorial Minute

At a Meeting of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences April 12, 2005, the following Minute was placed upon the records.

When he retired from the Celtic Department in 1986 as Professor of Irish Studies, John Kelleher had been a member of this Faculty for thirty-four years. When he died – New Year’s Day, 2004 – some nine weeks short of his eighty-eighth birthday, he still possessed the encyclopedic memory and mastery over all things Irish which had earned him legendary international standing.

To define that field, however, has always presented a challenge. At his retirement, John Kelleher was Professor of Irish Studies in the Celtic Department, a member of the Department of English, and also offered courses in the Department of History. Reflecting that background, his publications covered an extraordinary range: from Irish and Anglo-Irish authors at home and in America; to the history and Gaelic literature of early, medieval, and modern Ireland; to the Irish immigrant experience here in the United States. These scholarly papers were not numerous, but nearly every one was seminal.

Born and raised in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in an American-Irish community with strong ties to the mother country, he acquired informally a reading and speaking knowledge of Irish Gaelic. Later at Dartmouth, in addition to English literature he studied Irish history and Irish anglophone authors.

In 1940, John came to Harvard as a Junior Fellow and began a long association with Lowell House. He read Old Irish with Kenneth Jackson, first holder of the chair in Celtic Languages and Literatures. He also made friends with two fellow sons of Lawrence: Fred Norris Robinson, who pioneered Celtic Studies at Harvard, and the poet Robert Frost.

As a Junior Fellow, John found here a world-class library of and about the Celtic languages, literatures, histories, and cultures – and the largest collection of Irish materials outside of Dublin. He set to work with a will and always looked back at this period as sheer heaven. He married his childhood sweetheart, Helen Caffrey (Wellesley 1939), in the same interlude, which was brought to an end by World War II. Recruited to serve in military intelligence, John spent the Duration at the Pentagon’s Korean desk.

When he returned to Harvard after the war his hair was still dark, but soon he would be easily recognized at a distance for his shock of prematurely white hair. A tall, handsome and dignified man, he had the kind of erect bearing that made everyone around him stand a little straighter. His company was prized at Harvard for his quiet but sharp wit as well as his probity, and he was a gifted raconteur. Although the A.B. from Dartmouth was his only degree, he became a full professor in 1952 and in 1960 was appointed to the new chair of Modern Irish Literature and History, later to be designated Irish Studies.

Also around 1960, he concluded that no deeper understanding of early Irish history would be possible until he had really mastered the Irish annals. These collections of yearly notes had been maintained in monastic institutions on behalf of dynastic and religious patrons, at various times from perhaps the sixth to the fifteenth century. Untangling the mixture of facts, propaganda, and mischief, and coordinating it with the kings and kindreds named in Irish regnal and genealogical tracts, became for John a life’s work and his special contribution to Irish history.

The scope of that work he would describe years later in writing of his friendship with the novelist Edwin O’Connor, “When we first met,” he recalled, “I had just got myself locked into a lifetime affair with early Irish history, a matter of mistaking a mountain for a good-sized molehill due to the surrounding fog.” It is a measure of John’s sense of humor that he could go on to recollect O’Connor’s frequent salvos at his scholarly preoccupation. O’Connor had invented a character, one Bucko Donahue, purportedly an expert on the Irish annals. Bucko wrote to John claiming to have waded through the annals, genealogies and tribal histories – all in under a week. “The biggest barrelful of hogwash I’ve ever come across,” he wrote. “Well, you just keep right on with your work if you can keep fooling the Harvard lads. I’ve no respect for them myself. A few of them come down this way now and again; if we catch them we feed them to the turtles.”

John did keep on with his work, and his achievements did not go unnoticed. He received honorary degrees from Trinity College, Dublin and more recently the National University of Ireland, Cork (1999), where his former student, Professor Seán Ó Coileáin, predicted that “His exhaustive work on the annals and genealogies . . . will always remain as a monument to Irish learning, early and late.” A memorial service was held here on May 17, 2004, and his memory will be preserved in an annual lecture in his honor, delivered on the eve of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium.

Beyond the pioneering research, John carried a full course load almost every year at Harvard, taught also for nearly thirty years in Extension, and served the College for a number of years on the Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid. Not only a superlative scholar and teacher, he was a fine poet as well. His translations from the Irish and original poems were published by the Dolmen Press as Too Small for Stove Wood, Too Big for Kindling. Lines from it, though intended more generally, typify his modesty toward his attainments in Irish history:

Though I can’t look now and on the instant see Every plaque and crevice of the bark on the entire tree, It’s only in a way my sight’s begun to fail. There was always more to see than I had eyes for.

Certainly, no one else ever saw so much of it so clearly. John is survived by his four daughters Brigid McCauley, Peggy Oates, Anne Fisher, and Nora Stuhl; eight grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles W. Dunn

Gene C. Haley

Tomás Ó Cathasaigh

Patrick K. Ford, Chair