‘Angels’ director takes flight

Tony Kushner has encouraging words – lots of them – for aspiring playwrights

If anybody can discuss the rise of neoconservativism, Hannah Arendt on Walter Benjamin, Jesse Jackson on Terri Schiavo, and the future of the theater in 90 minutes, it’s Tony Kushner. As part of the Office for the Arts’ Learning From Performers program, the playwright appeared last Thursday at the Loeb Drama Center, where the American Repertory Theatre’s (ART) Associate Artistic Director Gideon Lester moderated a discussion with about 150 in attendance. When students from the ART Institute for Advanced Theatre Training took the opportunity to ask him about his 1985 play, “A Bright Room Called Day,” which they were, coincidentally, opening that night, Kushner was off and running: Philosophy, art, foreign policy, history, and the theater’s future were just a few of the topics he touched on.

Kushner speaks in a rapid-fire staccato, as though his mouth is in hot pursuit of his thoughts. The Pulitzer- and Tony Award-winning playwright is not known for shying away from tough topics, including criticism of his own work. He cheerfully informs his audience that he’s been accused of writing “huge sloppy messes.”

His magnum opus, “Angels in America,” is a two-part, seven-hour epic about AIDS in the “age of Reaganism,” while “Homebody/Kabul” involves a British housewife’s pilgrimage to Afghanistan. A navigator of sticky issues, Kushner doesn’t believe in preaching to the converted, a tactic he calls “nonsense.” Only when a writer is willing to introduce uncertainties, he asserted, can the rumblings of important art start to stir.

“You have to start at the place where faith breaks down, where you have confusion, where you don’t know what the answer is,” he told the audience. “It’s almost a guarantee that you’re going to go forward into things that are scary and risky, where you might say things that are not socially responsible. … I think the problem with writing plays is sort of mediating between your socially responsible conscious self and your irresponsible primary process – your creative, chaotic inner self. … If you start out at a point of confusion and go forward – and if you’re lucky and ask the right questions – you can really offer the audience … the possibility of thinking differently about the world and seeing the world differently, or at least acknowledging that there are areas of bewilderment and pain and loss and suffering. It’s not a fortune cookie.”

Hearing a VIP of contemporary theater encouraging his listeners to explore uncertain territory resonated with Susan Merenda ’07. “It’s exciting to hear someone in a position of expertise say that it’s OK to explore and see what happens. As a fledgling artist, the danger is ‘I don’t want to seem dated’ or ‘I don’t want to seem young.’ You feel like you have to know what you want to say versus saying, ‘This is something that interests me and I wanna invite the audience along for the ride.’”

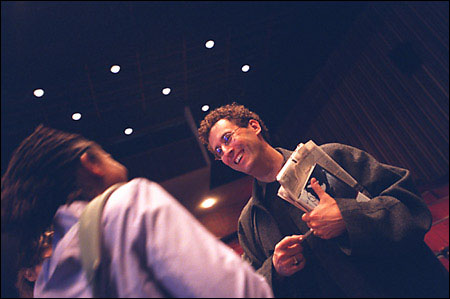

Kushner has a mop of tangled curls and gigantic hands that he flings about recklessly to accentuate his words. He speaks with conviction on the craft of playwriting, but to see him talk about anything else is to witness a chronic self-effacer in action. He’s an inveterate worrier – about conditions in Iraq, about the rise of the religious right in the United States about the corrosion of the National Endowment for the Arts, and about failing to live up to his reputation.

Art, however, often emerges from anxiety and struggle. Kushner acknowledges that despair informs much of his work. In “Only We Who Guard the Mystery Shall Be Unhappy,” a work still in progress, one scene features Laura Bush reading “The Brothers Karamazov” to dead Iraqi children. Kushner uses his preoccupation with the first lady and her love of books as a counterpoint to his “anguish” about the Bush administration and what he sees as its deafness to opposition to the war in Iraq.

Audiences have been astonished both by Kushner’s uncanny knack for being ahead of the political zeitgeist (he wrote “Homebody/Kabul,” which involves a Westerner’s fascination with the ancient Eastern city and its people, before the American invasion) and the Shakespearean flair with which he dramatizes specific historical events and characters (Roy Cohn, the right-wing, closeted lawyer with ties to Reagan, was the complex villain in “Angels in America”). His plays may have strong political leanings and he may be an activist, but his being a playwright, he asserts, is independent of his activism.

“I have a real allergy about artists confusing their work as artists with political activism, because I think these things are not at all the same,” he said. “Although art can have a political bent, the only thing that changes [conditions in the world] is direct political engagement.”

Kushner’s plays deal with a wide variety of political and philosophical issues, and their settings have a long global reach. But some of his work is close to home. Last year, “Caroline, or Change” appeared on Broadway. It’s a semi-autobiographical musical about a motherless Jewish boy in the South who befriends the family’s black maid, Caroline. Kushner says that Caroline was a tough character to put on paper.

“Writing Southern black speech is the hardest thing to do because when I was a white kid growing up in the deep South, making fun of the way black people talked was what you did if you were a racist kid, and it felt wrong, transgressive. It’s a complicated issue for people politically.”

But complicated issues leave ample room for mistakes, and making mistakes, Kushner reminds his audience, is the writer’s responsibility.

“The more you go afield in your own life, the more likely you are to make those mistakes, although in a certain sense, writing about yourself only brings you face to face with how little you know about yourself, which is sometimes a much more upsetting experience than realizing you know little about what it’s like to be [from Kabul].”

Despite his overwhelming concern for the state of the world, Kushner doesn’t project even a hint of weltschmerz. He has a sly sense of humor, which is inextricably linked to his anxieties.

“One of the greatest disadvantages of being a writer is you leave all this paper trail behind you of your stupid opinions,” he said, as the audience roared.

While the paradoxes of the world stubbornly lodge themselves around him, Kushner deals daily with the paradox of working successfully in theater, an endeavor that doesn’t always appear to be the most visible in society at large.

“Theater is hard. We live in a world of commodity objects and theater is not a commodity object,” he lamented. “It never finishes, it’s never complete. It changes every night. It freaks people out. It’s really difficult to sit through. It’s really embarrassing – or at least there’s the threat of an embarrassment hanging over it. Every performance you go to, you’re in the room with vulnerable human beings. It engages you as a sadist. It engages you as a masochist. It’s sexy and really not sexy; and believable and really not believable.”